MAPMAKING: An introduction to ITERARTE

Since the very earliest days of human creativity, art has been a way to manifest and share with others personal and collective sentiments and experiences, a wayfinding mission to make sense of our place in the world. It has, in its many different forms, been an essential navigator through times of triumph and catastrophe. As we all make our independent journeys through our lives, art can empower us. This is at the heart of ITERARTE's mission, and indeed its name – that comes from the Latin word for journey, we are aware of the itinerant nature of our lives today. ITERARTE is a space for artists, artisans, collectors, and art enthusiasts of all kinds to find direction, to be inspired and spark new collaborations.

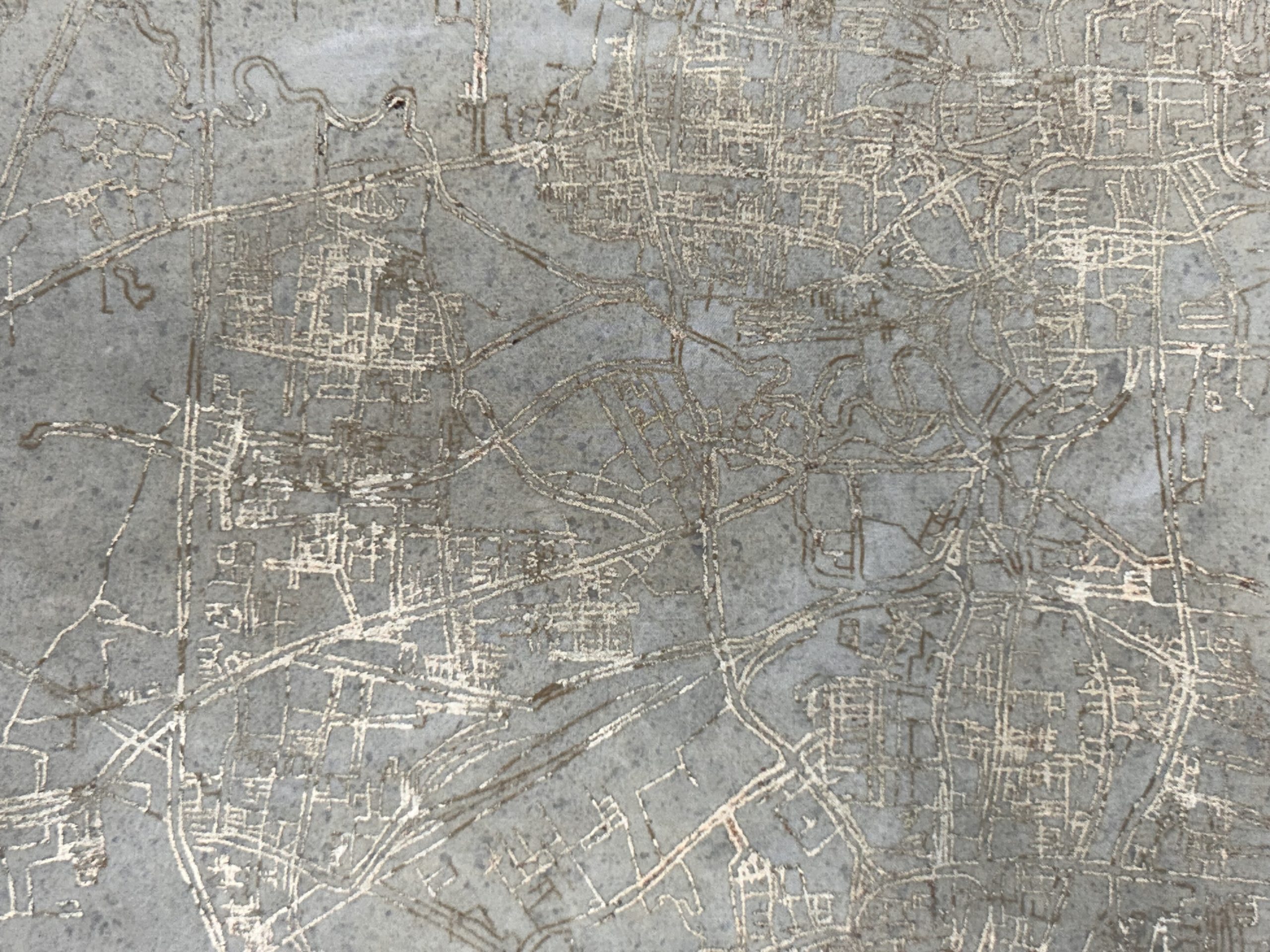

It is fitting that the opening exhibition to launch the venture is one that focuses on the concept of mapping – a London debut for the artist Nidhi Khurana, with the evocative title ‘Traces of Existence: Places Between Places’. She is widely travelled, and claims that to learn a city, you need to get lost. Her maps are executed exquisitely in diverse media, from fabrics sourced in second-hand markets and recycled scraps to gold leaf, silver, and silk. Not precise cartographic records by any means, they are indeed evocations on her experiences in different environments and reflections on the world around us. It is often in those in-between spaces where the magic happens.

The relationship of maps to time is fascinating to consider. Maps are some of the earliest examples of mark making by humans, many of which still survive today. During medieval times, elaborate Mappa Mundi were created, offering fascinating insights into the known world, about to be revolutionised forever by explorers. Maps are collected by cultural institutions across the world, the largest being at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. that includes around 5.2 million maps, and the craftmanship and beauty of maps and globes as objects and works of art is unquestionable, as visions of the world. (Louvre Abu Dhabi presented an exhibition in 2018 with this title). And yet, the maps we use today to incessantly chart our daily journeys, which we view on a digital device, are in constant flux. Google Maps is updated every second of every day, instantaneously reflecting new information from satellite imagery, street view cars and even us as users. It strictly follows the utilitarian concept of a map, to get us most efficiently from point A to point B. So how can these two realities co-exist? And how can artists respond?

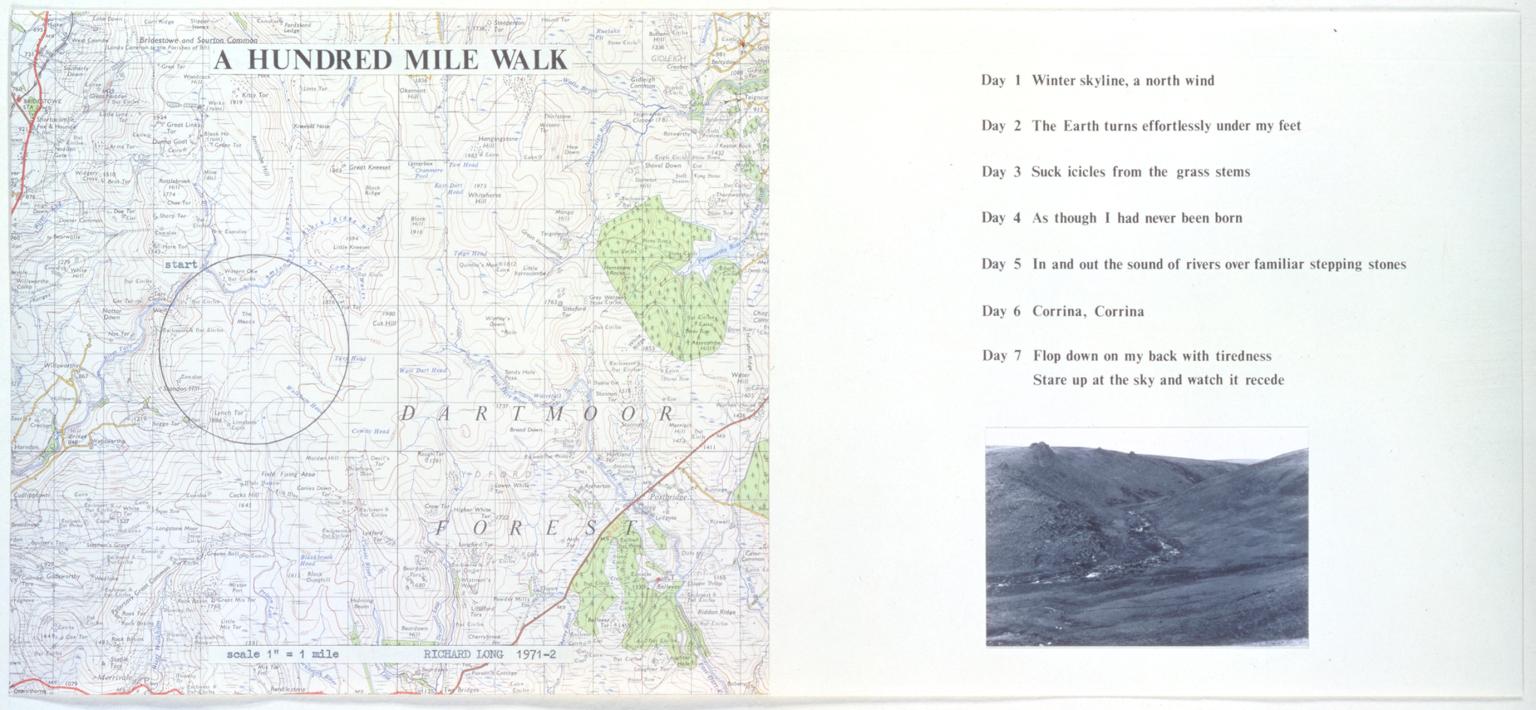

Artists have frequently used maps as a medium in their practice, to quote Maggie Gray, an academic and the curator of the exhibition The Art of Mapping, “today’s artists use maps to highlight and challenge the way we order the world.” She goes on to point out that “we use maps in the assumption that more often than not, they will display what we already expect to see,” and perhaps it is here that artists have the opportunity to wrong foot us and circumnavigate google maps, as Khurana’s mediations show us. Maps accompany us on a journey, they offer companionship, detail, information. Many artists in the Land Art movement used maps as a method of recording journeys, such as Richard Long, for whom the walk itself was his artistic medium, the finished artwork either being a notated copy of his ordnance survey map, photography, or a sculptural response to a walk using natural materials.

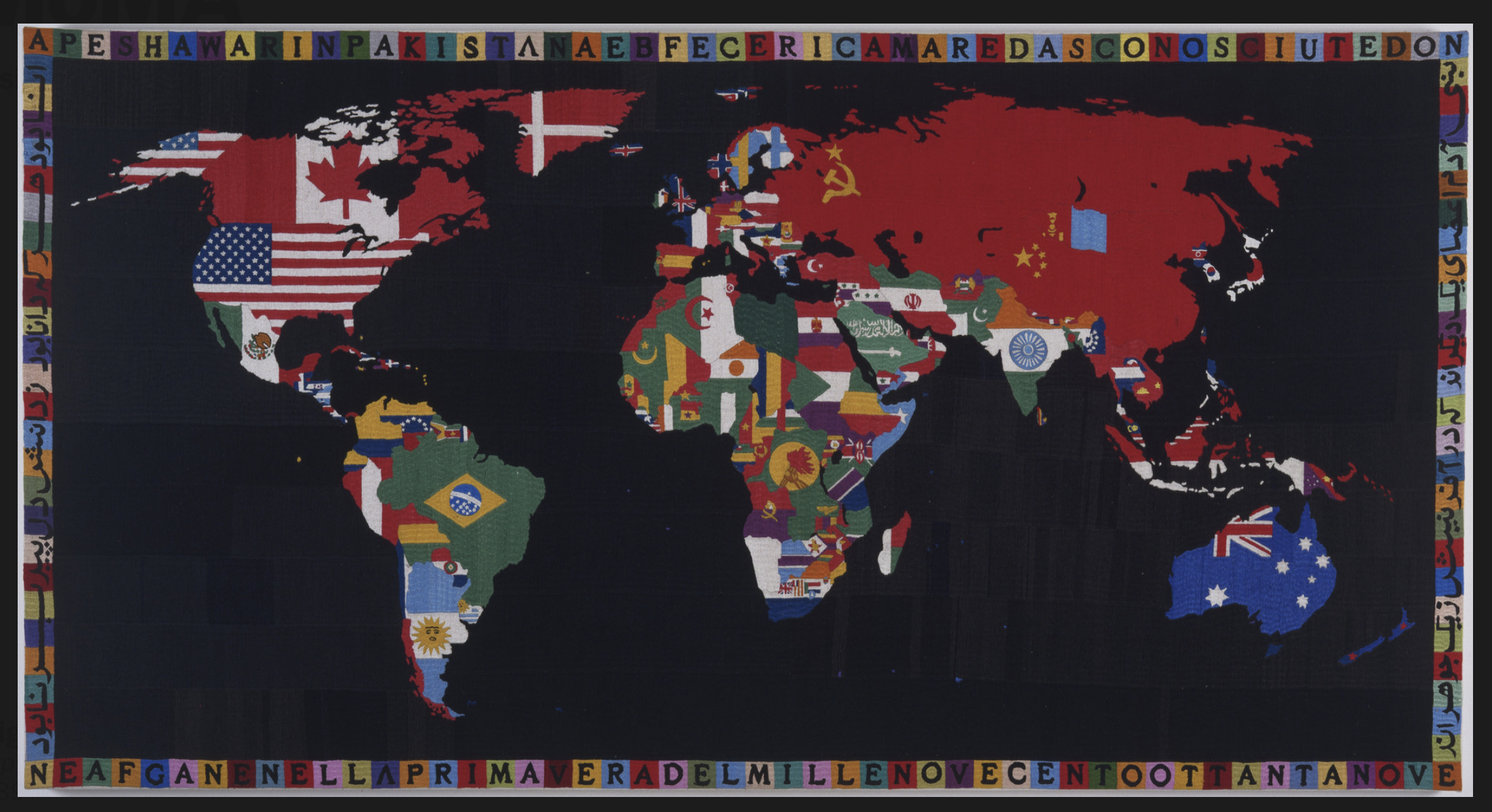

A lot has been written about artists and maps, The Museum of Modern Art, New York offers a good selection, bringing together works in their collection under this theme. Another resource is The Map as Art, by Katharine Harmon. Maps have always been inherently political, in the majority of cases that is why they were originally created and shared - and this can be a starting point for artists. Khurana acknowledges that many of the maps she started from were colonial in nature. The seminal work that tackles this is Alighiero Boetti’s Mappa series, begun in 1971 and continuing for twenty years. The Italian conceptual artist, a member of the Arte Povera movement, commissioned Afghan embroiders to create maps of the world, with each country bearing the colours and pattern of its flag. Over the course of two decades there were significant geopolitical changes throughout the world, such as the break-up of the Soviet Union and disputes over territories in the Middle East, and all were reflected in these works of art. Other iconic works include Simon Patterson in The Great Bear (1992) who changes the names of the London underground stations to recognise individual Londoners, and many by Grayson Perry, who has made maps a key subject in his work in many forms, from ceramics to etchings and large scale tapestries, achieving a balance between imagined worlds and his lived reality. It all begins in childhood. This is an extract from the novel A Stitch in Time:

She liked maps. She liked to know where she was and moreover had a deep secret pride in having learnt all on her own how to find her way around a map. Once upon a time (and not so very long ago, either) maps had been as mysterious to her as the long columns of print in her father’s newspaper, or some of the more confusing kids of sums at school, before which she sat in baffled horror. There were these maps with networks of lines all differently coloured which might be roads or rivers or railways, but you could never be certain which, and their blocks of green and blue and grey which meant other things, and their innumerable names. And there were the places to which they referred, bright and moving with houses and buses and waving trees and bustling people, and how on earth you married the one to the other, she could not see at all.

The protagonist, Maria, an only child aged 11, goes on to describe a moment of pure epiphany, when she suddenly works it out, makes the connection between the two-dimensional lines on a piece of paper and the buildings and streets she was immersed in.

Maps make explorers of us all, and we are all mapmakers.

Related Articles

Read more +19 February 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in COMPASS

Read more +19 February 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in COMPASSThe Time is Now: How Artists Respond to the Idea of Time

The Magazine

Recent Posts

-

Cultural Diplomacy and Artistic Dialogues: Exploring ‘Beneath the Gaze of the Palms’

Cultural Diplomacy and Artistic Dialogues: Expl... -

The Time is Now: How Artists Respond to the Idea of Time

THE TIME IS NOW: HOW ARTISTS RESPOND TO THE IDE... -

Cultural Crossroads: Stories of Exchange

CULTURAL CROSSROADS: STORIES OF EXCHANGE Januar... -

Colour Series Part IV: Purple

COLOUR SERIES PART IV: PURPLE The colour purple... -

On Embroidery & Motherhood with Iliodora Margellos

On Embroidery & Motherhood with Iliodora Ma...

WANT TO STAY UPDATED WITH ITERARTE LATEST ACTIVITES AND NEWS?

Sign up to our newsletter to be one of the first people to access our new art, learn all about our latest launches, and receive invites to our exclusive online and offline art events.