ARTWORKS

Marwan Sahmarani

NIDHI KHURANA

In this episode during a visit to his Beirut studio, Marwan Sahmarani discusses with Founder Tamara Chalabi his artistic practice; what and who inspires him; […]

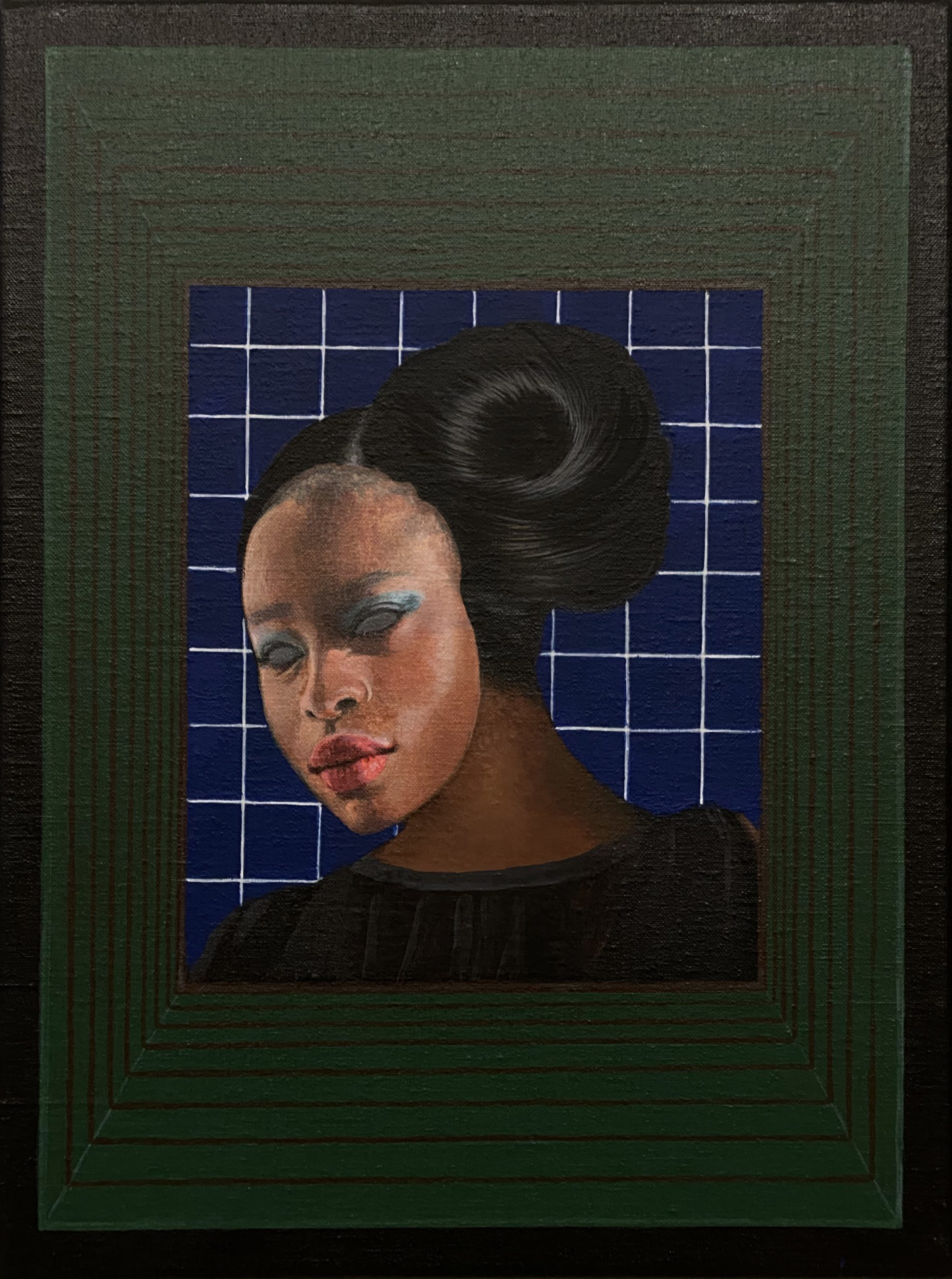

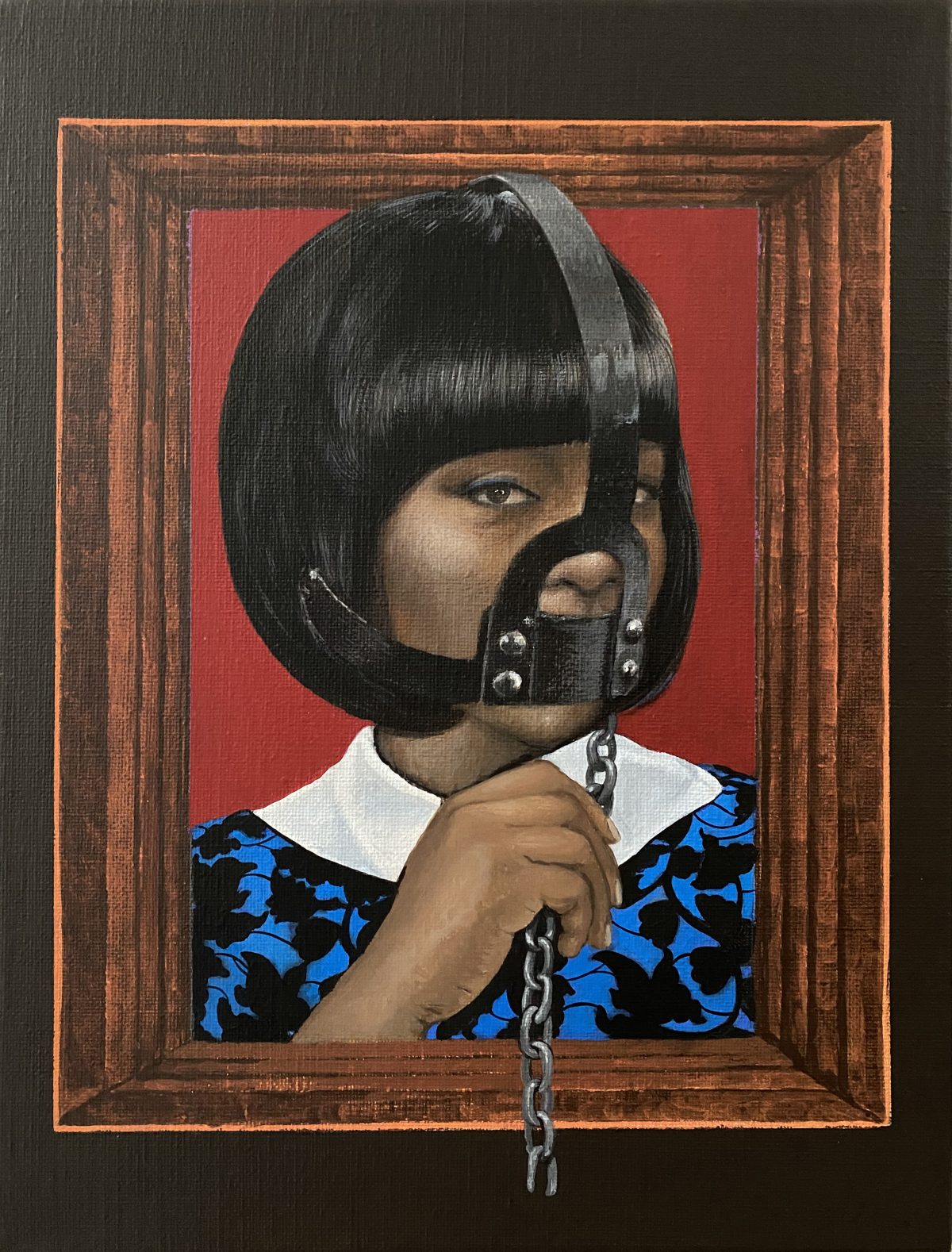

Iranian-born artist, Maryam Najd, moved to Antwerp, Belgium in her young adulthood and developed a practice rooted in the European tradition of portraiture painting. Her works, particularly in her most recent series, look to Surrealism as another source of inspiration, painting women in obscure settings as a means of questioning gender and race distinctions. The interrogation of oppressive structures as part of her conceptual practice, as well as the figurative technique she employs, can be traced back to the Belgian Surrealists. The influence of the Surrealists can be seen in other contemporary examples across the globe, particularly as a way to envision a liberated space for women and other marginalised groups.

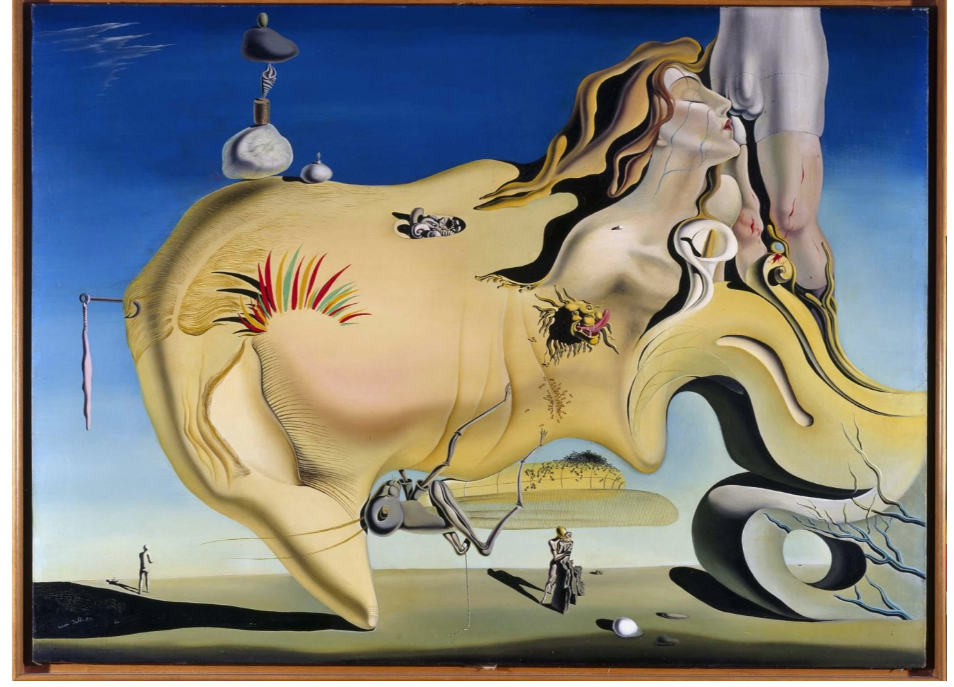

When speaking about Surrealism, we must recognise its Parisian origins, which echoed the rhetoric of Sigmund Freud. Psychoanalysis principles and divergence from cultural rationalism defined the distorted fantasies found in the works of famous artists like Salvador Dali and Max Ernst. Andre Breton’s 1924 Surrealist Manifesto sought to revolutionise the human experience by embracing the unconscious, describing the movement as “dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason, outside of all aesthetic and moral preoccupation.”

The genre birthed the lesser known and rebellious strand, the Belgian Surrealists, who rejected automatism as well as several other components, and instead focused on recognising the surreal in the everyday. The poets, Paul Nougé, Camille Goemans, and Marcel Lecomte published Correspondance shortly after Breton’s manifesto, seeking to challenge convention through the idea of ‘radical clarity’.

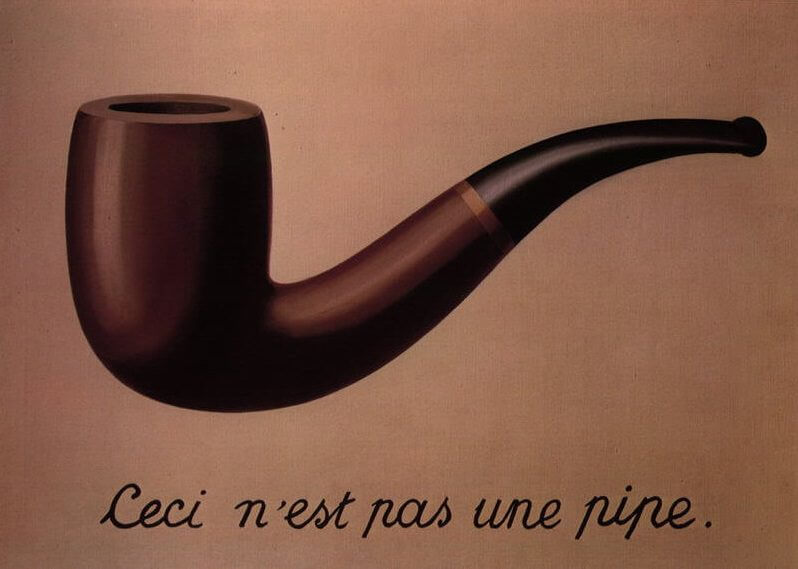

Nougé was the leader and writer of the movement, who provided the intellectual strategy of Belgian Surrealism, writing many of the titles for the most recognised figure of the movement, Rene Magritte. By proposing to radically alter the confines of words from their literal meaning, he envisioned a form of visual art and poetry which would liberate people from conventional thought.

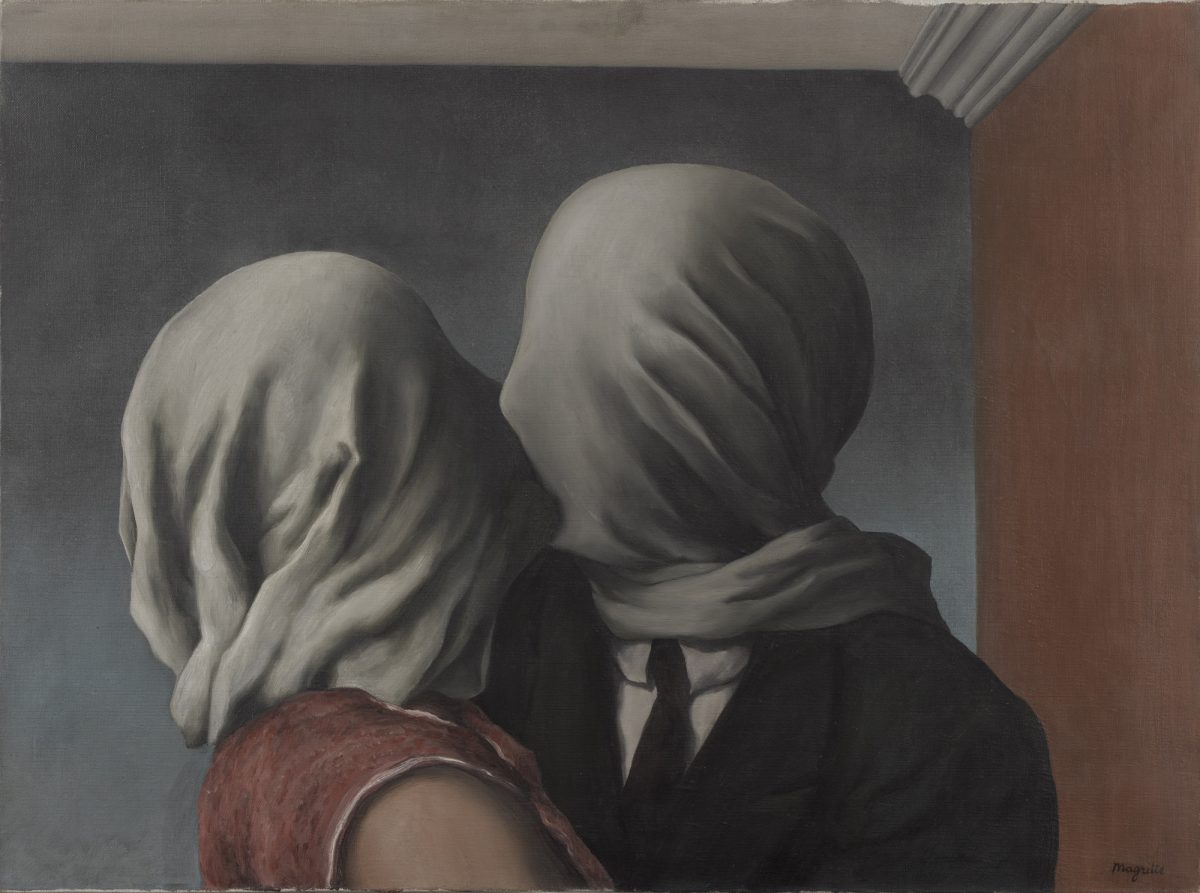

Each of Magritte’s iconic works, such as The Son of a Man (1964) and The Treachery of Images (1929), are a testament of his aim to “make the most everyday object shriek aloud.”

His figurative style to portray these absurdities was unusual for the Parisian Surrealists but gained sustained global traction. The juxtaposing technique can be seen in Najd’s naturalistic portraits of women confined with metal masks or peeling away from their own skin, as she addresses the issue of self-censorship in many societies such as her native Iran. The mask may also be a reference to the Surrealist interest in literal and metaphorical disguises which hide realities beneath the surface.

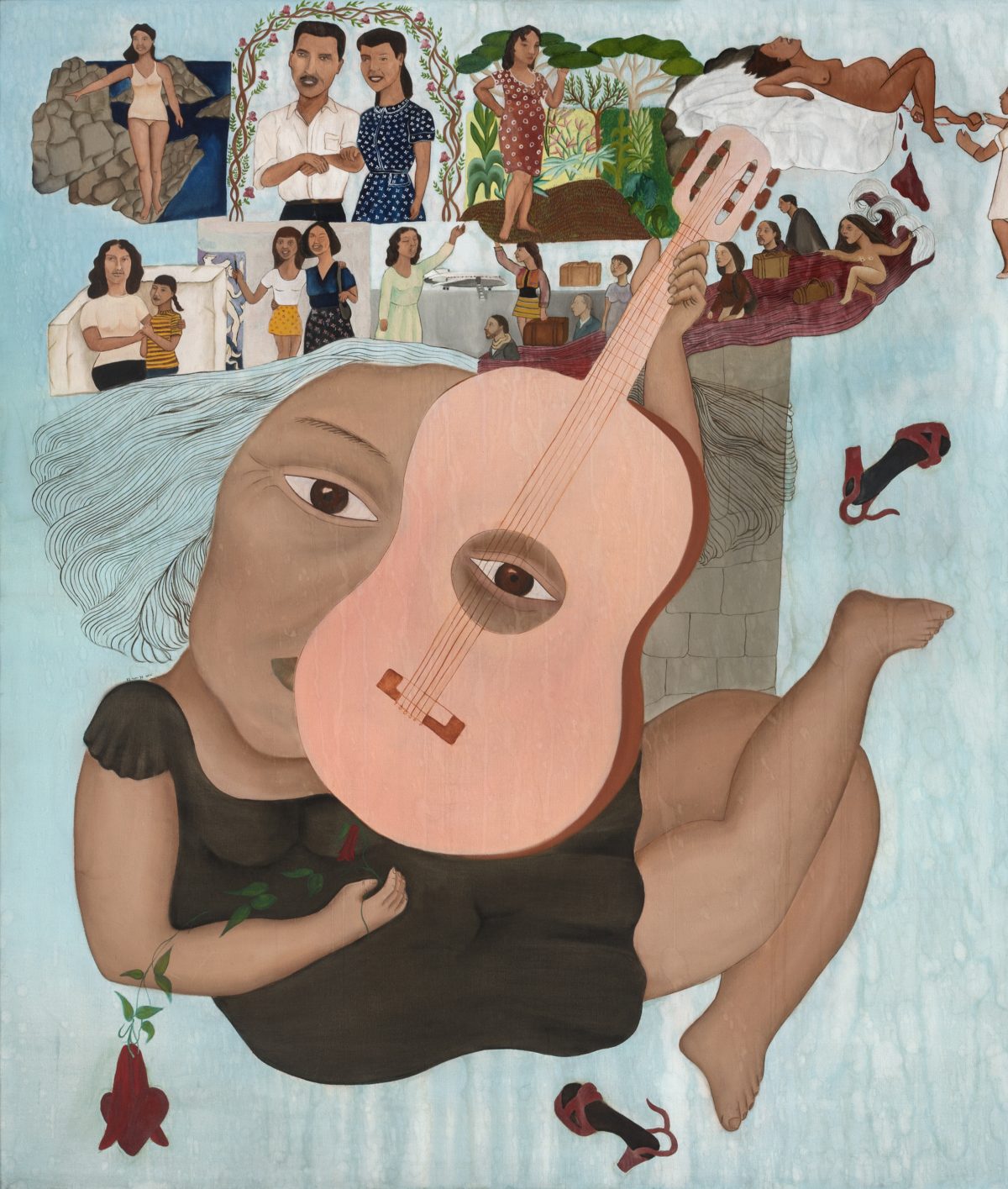

Feminine interpretations of the movement have also thrived in recent years, such as in the 59th Venice Biennale titled The Milk of Dreams, where curator Cecilia Alemani showcased a number of contemporary female Surrealists, including Mexican artist Leonora Carrington and Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña. Vicuña’s Bendigame Mamita (1977) was one of the most evocative works of the 2022 biennale, featured on public transport boats (vaporetti) around the city. A portrait of her mother dreaming, the image is happy and diverting, contrasting with the horrors the artist faced during Pinochet’s regime.

The anachronistic oeuvre of Najd, who combines features of Persian miniature painting with a contemporary figurative artistic style, can be compared to Paul Delvaux’s distinctive iconography of classical architecture, dream-like landscapes, and skeletons in his take on Surrealism. He was influenced by the poeticism and illogical content of Magritte, though was not interested in becoming a formal member of the Belgian group.

The impact of the Belgian movement and Surrealism as a cohort continues to penetrate contemporary art movements, with artists like Najd using its methods towards collective and artistic emancipation. Suzanne Cezaire’s 1943 writing, Surrealism and Us discovered a new form of resistance for African and Caribbean diaspora whilst reinventing the western genre, thus unveiling Afro-Surrealism. This evolved with the development of Afrofuturist art which was recently invigorated in Ekow Esun’s In the Black Fantastic at Hayward Gallery in 2022. It featured Nick Cave’s ‘Soundsuits’, flamboyant wearable sculptures that conceal the wearer’s identity, made in response to the brutality faced by Rodney King.

More recently, Najd has looked to the Art and Liberty movement in Cairo for her inspiration, which continues her study of censorship. It was formed after the Second World War as a rejection of rising fascism and nationalism in Europe, its momentum occurring between the late 1930s and 1940s. The manifesto written by Georges Henein looked to individualism and imagination as tools for revolution, referring to a future of free expression where Socialism was embraced. The practices of artists such as Ramses Younan and Angelo de Riz followed the guidelines of Parisian Surrealists, with their distorted structures and divergence from artistic convention and yet forged a new pathway.

Perhaps Surrealism still has the power to interrogate societal convention through its propositions of alternative realities. But it makes us question – have all of these sub-movements evolved into completely different genres in their own right, separate to the historically-established, psychoanalytical premises? Just as Nougé suggested, it may be best to free ourselves from the confines of such titles.