- Home

- First Principle

- Origins: Tracing Material Culture

Origins: Tracing Material Culture

Origins:Tracing Material Culture

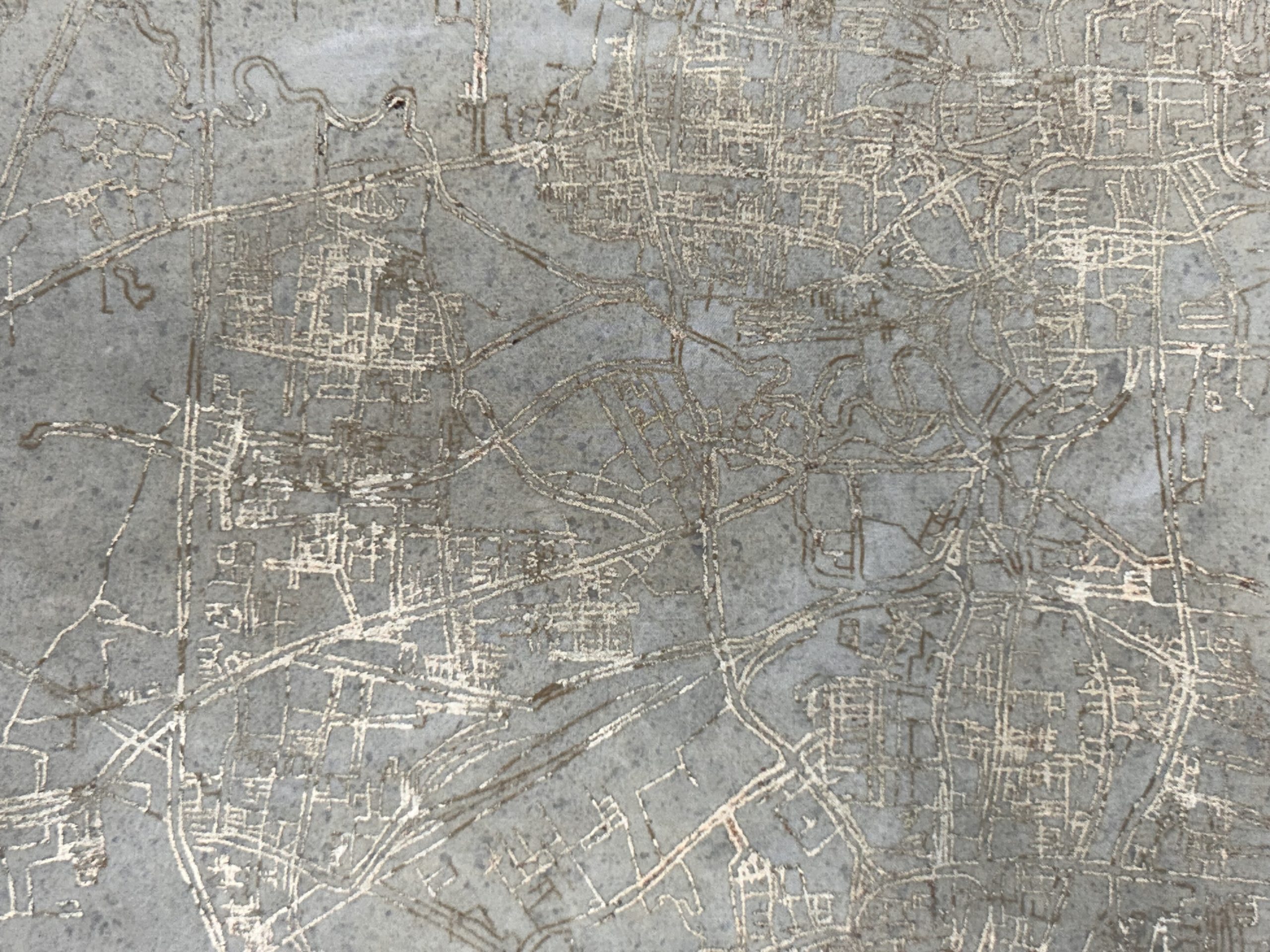

Conversations regarding Nidhi Khurana’s and Nuveen Barwari’s works interplay with contexts of materiality, as their shared use of textiles project historical and social existences. Both artists employ processes in which their ideas inform an intuitive choice of material, often repurposed to navigate the meaning and making of their work. Khurana uses silk as the canvas on which she imprints her mapping to improve the connections with her landscapes, whereas Barwari manipulates the fabric to comment on the cultural motifs personal to her community.

Material culture refers to the physical objects that humans interact with and attach functions, meanings and value to. Objects in turn become a shorthand for social and cultural reality or memory, so people use them as a form of belonging. Brown’s ‘Thing Theory’ suggests that objects can become things when their primary use no longer serves us; what may be an object of use to someone in one instance, in another context can become something that people can study to draw conclusions about a group of people in a certain time. This also allows us to make the distinction between art and craft, with art essentially removing the function of a made object, a concept explored in Duchamp’s ‘readymades’.

By confronting a silk fabric’s ‘thingness’, we can obtain a glimpse of a history of the craft, as well as the ancient myth and cosmologies surrounding it.

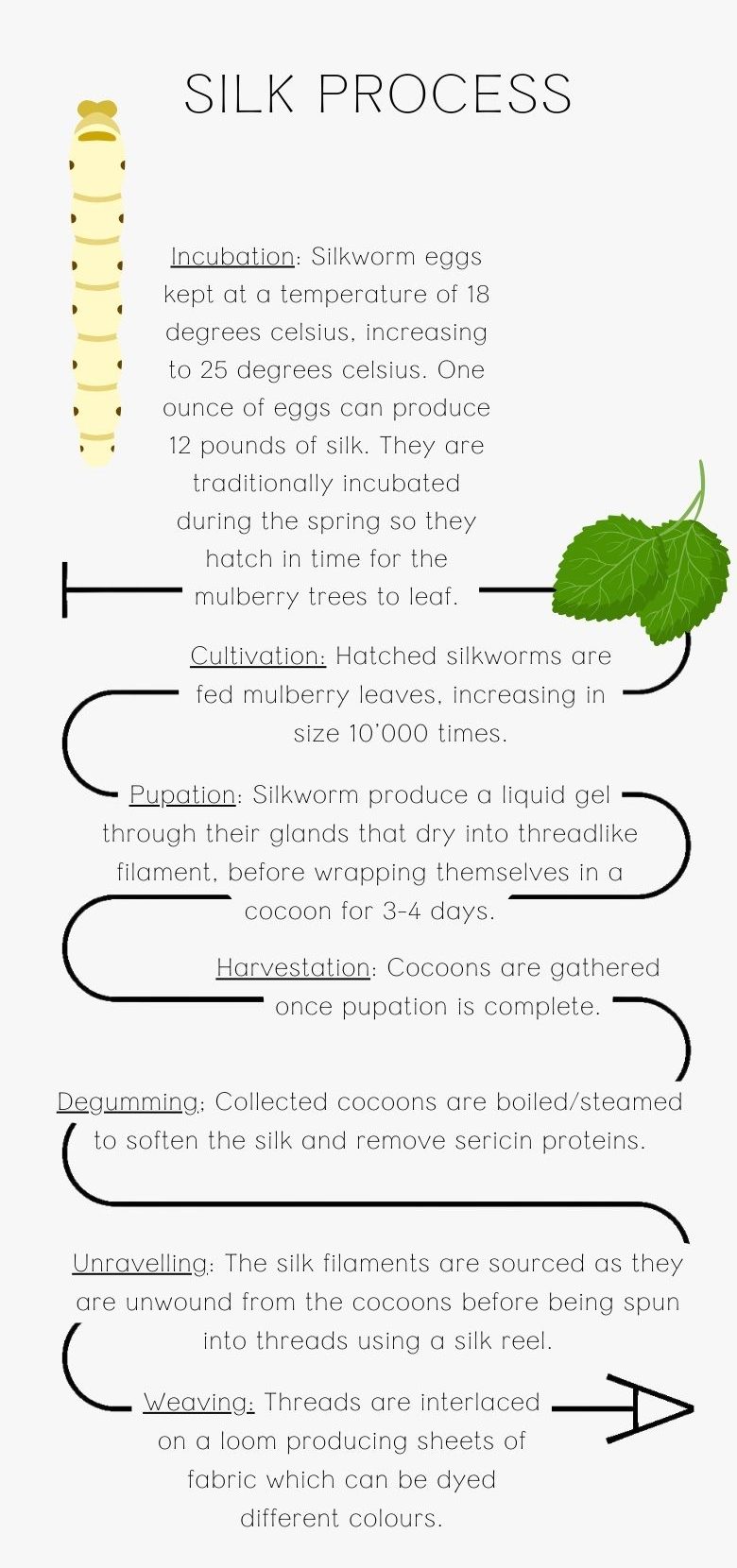

The origin of silk can be traced back to China in the Neolithic period, where it held a monopoly over its production for thousands of years due to the guarding of the sacred knowledge of sericulture. According to Confucius, the famous Chinese philosopher, a princess named Xi Ling Shi was the first to unravel silkworm cocoons to reel the silk filament in a continuous strand after one fell into her tea. She then observed the silkworm’s life cycle and invented the tools to be used to weave the filaments into beautiful fabrics. As a result of her discovery in 2700 BC, she was made a goddess and patron deity of weaving.

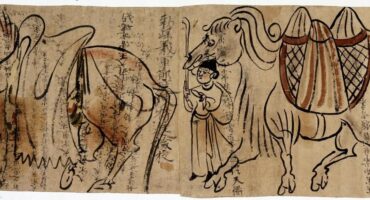

The famous Silk Road network of trade was established across sea and land channels to pass on luxury Chinese silk fabrics and other goods through Central Asia to the eastern coast of the Mediterranean, initiating a cultural and economic shift in global trading. Knowledge of the silk-making process reached the Byzantine Empire by 550 AD, and Constantinople became a hub for the silk industry. Thus, silk cultivation was subjected to many different variations in technique and usage, for example, the Indian tussar silk was produced by allowing the moths to hatch due to Hindu and Jain traditions prohibiting the killing of the pupae inside the cocoon. However, China still maintained mastery over their techniques and still owns almost half of worldwide silk production, made using its traditional techniques.

Although the Silk Road was mainly used for commercial gain, the movement between East and West also allowed for other forms of cultural exchange to take place, including science, philosophy, religion, and food. This concept of interconnectedness and exchange between humans due to geographical exploration can be applied when discussing Khurana’s personal experiences of travel through her mapping.

For Nidhi Khurana, the choice of material is a nod to the ecological histories she is interested in. Her layering of silk and other rich materials such as gold and silver to produce her interpretations of cartography enhances the spatial connection between herself and Delhi, and broadly addresses the interplay of man and nature. She explores this through gaining inspiration from both urban and natural environments as well as from artisanal practices that make deeper connections with materials from the earth. She encourages the continuation of traditional practices such as naturally dying silks, claiming that man-made developments such as AI cannot replace these authentic encounters with the world. Her works embody her personal Silk Road as her practice takes on the cultural influences of each place she visits.

Nuveen Barwari’s transformative use of textiles presents the intricate nuances of her diasporic experience, as she uses fabric deconstructed from Kurdish dresses and rugs to navigate her conflicting identities. Having lived in both the US and Kurdistan, Barwari’s practice is shaped by her experiences of assimilation and displacement. Her works occupy the subliminal space between homeland and host land, with materials performing as tools of resistance towards an ongoing liberation movement. In her published essay, Barwari explains she is informed by the layering of colourful sheer fabrics in ‘Jilli-Kurdi’ (Kurdish dress) to create her art, emphasising her layered identity and the cultural symbolism attached to ceremonial dresses. These pieces of clothing are not only decorative symbols, but their fragmentation leads to the artist’s redrawing of borders and reconnecting to her ancestral land.

“The Dress-as-collage and as an expression of protest has taught me everything I know about my motherland, my mother tongue, and my mother.” (Barwari, 2022)

As demonstrated in the recent Barbican exhibition, the use of textile in contemporary art can be used to interrogate hierarchies of power by subverting the craft’s intended use for producing clothing. However, wearing the Kurdish dress is a consistent form of protest whether it is used in art or worn in public places, due to the ongoing struggle to claim recognition. For instance, the Kurdish dress became a symbol for solidarity online after a man was punished by police in Iran by parading him on the streets wearing traditional women’s clothing.

Kurdish women are not only faced with oppression from outside their community, but also within the patriarchal conditions of marriage and labour. By utilising the shiny, sheer qualities of fabrics such as Funeral Dress, many patterns underneath appear and disappear based on perspective and lighting, reflecting the varied roles of women in Kurdish society. Barwari reiterates that complex interactions between humans and things do exist, with clothes providing intimate clues about the people who wear them. Ultimately, material culture is essential to the preservation of identity within and between groups of people, and allows contemporary artists to manifest more social meaning into their work.

Related Articles

Read more +19 February 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First Principle

Read more +19 February 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First PrincipleCultural Crossroads: Stories of Exchange

Read more +16 January 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First Principle

Read more +16 January 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First PrincipleEditions & Multiples: Art in Repetition

The Magazine

Recent Posts

-

Cultural Diplomacy and Artistic Dialogues: Exploring ‘Beneath the Gaze of the Palms’

Cultural Diplomacy and Artistic Dialogues: Expl... -

The Time is Now: How Artists Respond to the Idea of Time

THE TIME IS NOW: HOW ARTISTS RESPOND TO THE IDE... -

Cultural Crossroads: Stories of Exchange

CULTURAL CROSSROADS: STORIES OF EXCHANGE Januar... -

Colour Series Part IV: Purple

COLOUR SERIES PART IV: PURPLE The colour purple... -

On Embroidery & Motherhood with Iliodora Margellos

On Embroidery & Motherhood with Iliodora Ma...

WANT TO STAY UPDATED WITH ITERARTE LATEST ACTIVITES AND NEWS?

Sign up to our newsletter to be one of the first people to access our new art, learn all about our latest launches, and receive invites to our exclusive online and offline art events.