- Home

- Itinerant Trails

- Colour Series Part IV: Purple

Colour Series Part IV: Purple

COLOUR SERIES PART IV: PURPLE

The colour purple is one of the most captivating pigments, sitting at the far end of the colour wheel and considered the hardest for the eye to discern. Exuding mysticism and ambiguity, it is the result of the combination of two primary colours, red and blue. Whether it be lilac, mauve, violet, or byzantium, the colour’s story is woven into the fabric of ancient civilisations and modern cultures.

The origins of purple are steeped in legend as well as history. In Greek mythology, it was Hercules’ dog that accidentally discovered the dye, after chewing a sea snail on the beach which turned his mouth a deep shade of purple. This is not too far from the truth - the famous Tyrian Purple was first produced by the Phoenicians in Tyre (in present day Lebanon) in the 16th century BCE by extracting the coloured mucus from sea snails found in the Mediterranean and leaving them in the sunlight for a period of time. The dye required thousands of snails just to make one ounce of it and was a notoriously unpleasant process, causing putrid smells in the areas it was produced. However, its bold colour and long-lasting quality made it worth more than its weight in gold.

Despite its origins, purple has long been a symbol of luxury, power, and exclusivity since antiquity. In Ancient Greece, the colour was a mark of divine and royal authority. Reserved for royalty and high priests, its use was strictly controlled by legislation. The term “purple” comes from the terms porphura in Greek or purpura in Latin to describe the dye.

In Rome, Julius Caesar famously wore a purple toga, whilst senators could wear a purple trim on their robes. The colour was so revered that some Roman emperors even imposed the death penalty on lower-ranking citizens caught wearing it. Beyond the Mediterranean, Persian king Cyrus the Great, was said to wear a purple tunic as his royal uniform, further cementing purple’s association with regality.

Purple’s prestige grew with time, becoming the imperial colour of the Byzantine and Holy Roman Empire (prompting the name of the colour Byzantium). The children of emperors were bestowed the title Porphyrogenitus, meaning “born in the purple.” The Great Palace of Constantinople, built for Prince Constantine, featured a room for royal births lined with porphyry, a rare purple-coloured marble quarried from the deserts of Egypt. Porphyry can be seen in many examples of Roman sculpture and architecture.

Named after the ancient city of Tyre where it was centrally produced, Tyrian Purple was traded along the Silk Road, spreading to the Middle East and North Africa, but remained accessible to only the higher echelons of society. Production of the dye disappeared after the fall of the Byzantine Empire in the 15th century, and it wasn’t until it was synthesised accidentally by British chemist William Henry Perkin in 1856 that it became widely available to the non-elite. Known as the “Mauve Decade”, the colour was popular with the Impressionists, with many using the hue in their explorations of light.

For ITERARTE artists Paolo Colombo and Lydia Delikoura, both based in Athens, purple continues to carry profound cultural and historical resonance. Drawing inspiration from Byzantine art, they weave the colour into their works, such as Imperial Purple (2024) and Lady Chatterley’s Lover (2022), creating pieces that exude an ephemeral quality whilst subtly embedding the rich connotations of colour and form into their meaning. Purple acts as a bridge between past and present, a testament to its enduring power.

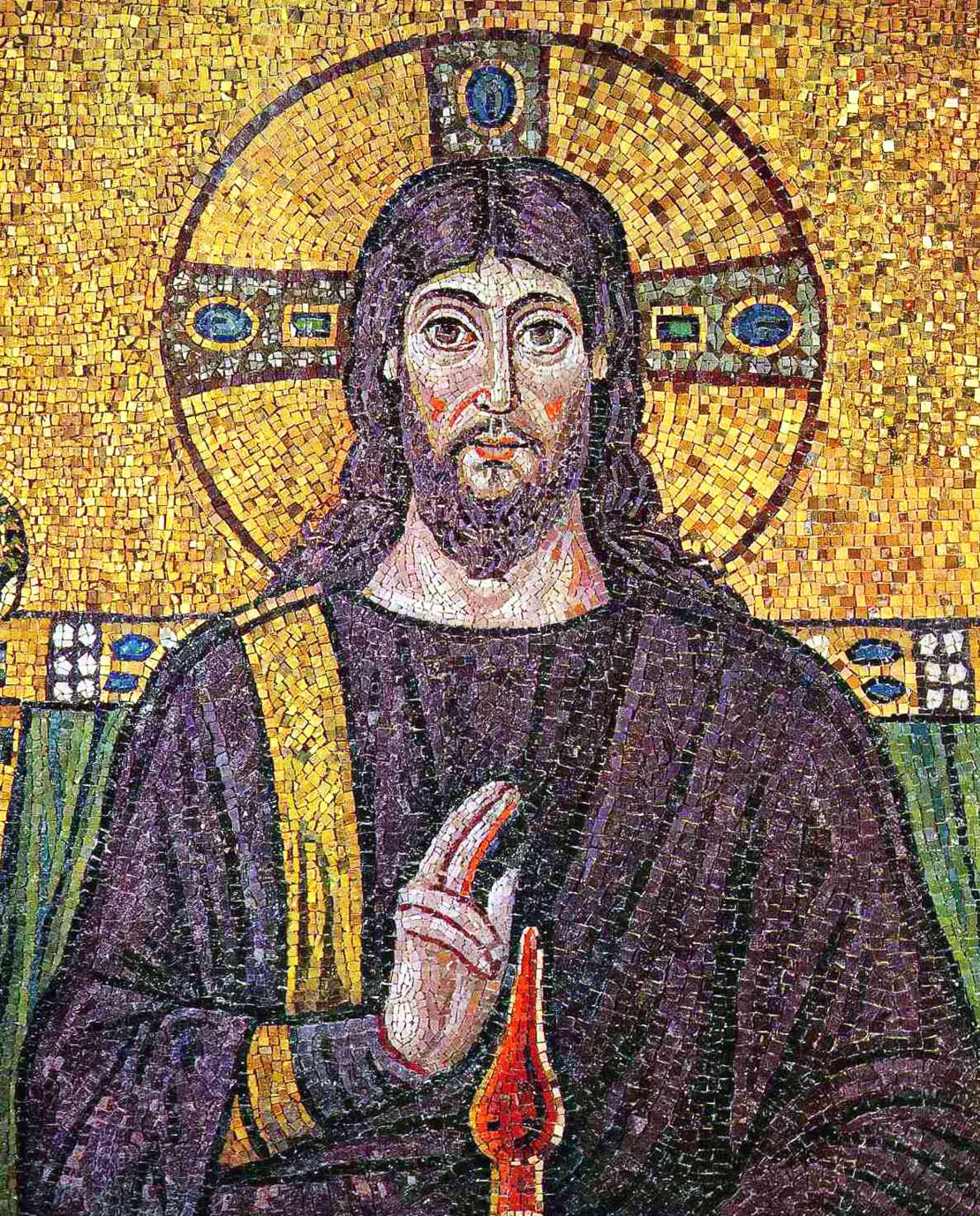

The allure of purple for centuries may also lie in its resemblance to clotted blood, making it a fitting choice for the Catholic church during the medieval period. Jesus can be seen depicted in purple robes in Roman churches such as the San Vitale Basilica mosaics and the walls of the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel. Despite the demise of Tyrian purple, the colour retained its spiritual significance, becoming a symbol of sacrifice and penance, and featured in Christian traditions such as Advent and Lent.

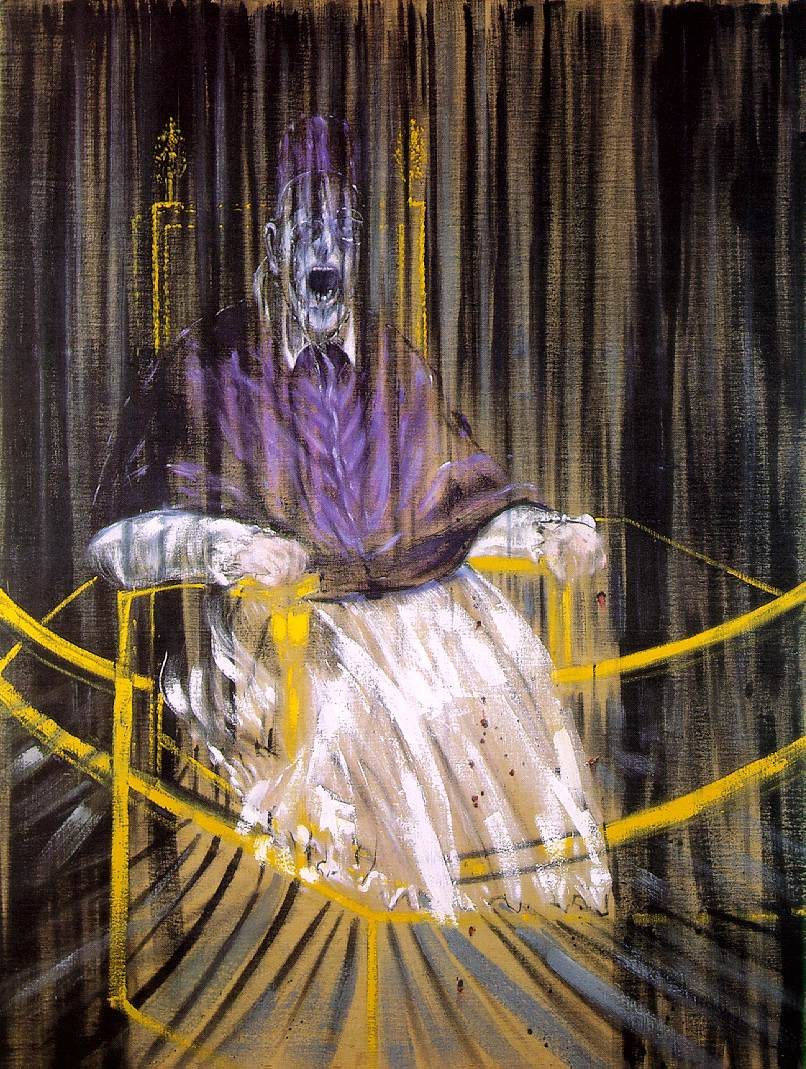

Francis Bacon’s 1953 Study After Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X reimagined the pope’s robe in violet instead of the original red, a choice perhaps reflecting purple’s historical ties to the Church. Visually, the violet hue intensifies the emotional impact of the pope’s anguished expression and adds a visceral intensity to the work - reminiscent of Derek Jarman’s contemplations of colour in his book Chroma: “if anger is red then rage is purple”.

In contemporary art, purple has also captivated artists exploring the beauty and complexity of natural and spiritual worlds. Georgia O’Keefe employed lilac tones in her study of petunias to evoke the sensuality of nature and Hilma Af Klint, who participated in seances, used it repeatedly in The Ten Largest (1907) series to capture the stages of life.

Many purple-coloured natural materials are used by people across the world for spiritual healing and stress relief, such as lavender flowers and amethyst gemstones - the crown chakra, the highest level of consciousness, is linked to purple.

The film Purple (2017) by Ghanaian artist John Akomfrah addresses environmental concerns through a hypnotic narration of disappearing landscapes using archival footage shown across six channels. Premiering at the Curve, Barbican, the carpet and walls of the viewing room were purple - “Purple is a colour of hybridity, a mix of blue and red, an in-between. It’s not natural, it’s constructed.” (John Akomfrah, 2017) In some cultures, such as in Thailand and Ethiopia, wearing purple is a sign of mourning, therefore Akomfrah may also be referring to a shared sense of grief towards the lost environment.

A more recent example is Christina Kimeze’s 2025 exhibition Between Wood and Wheel at the South London Gallery, on until 11 May 2025. The exhibition features a striking array of purple hues, rendered in her signature gestural strokes, bringing to life vibrant scenes of community and connection. Using oil pastel, some works depict dynamic moments of Black roller skaters in London, capturing both the energy and intimacy of these gatherings. With a particular focus on women, either based on family and friends or folkloric characters, her recurring use of lilacs and mauves imbues the works with an aura of femininity and freedom. Paired with the movement of her strokes, purple allows her to explore what she describes as “the idea of existing between two emotional spaces.”

Related Articles

The Magazine

Recent Posts

-

Cultural Diplomacy and Artistic Dialogues: Exploring ‘Beneath the Gaze of the Palms’

Cultural Diplomacy and Artistic Dialogues: Expl... -

The Time is Now: How Artists Respond to the Idea of Time

... -

Cultural Crossroads: Stories of Exchange

... -

On Embroidery & Motherhood with Iliodora Margellos

... -

Colour Series Part III: Red

...

WANT TO STAY UPDATED WITH ITERARTE LATEST ACTIVITES AND NEWS?

Sign up to our newsletter to be one of the first people to access our new art, learn all about our latest launches, and receive invites to our exclusive online and offline art events.