- Home

- TÊTE-À-TÊTE

- PAOLO COLOMBO

PAOLO COLOMBO

PAOLO COLOMBO

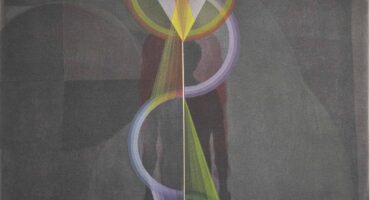

Colombo’s artistic rebirth was as humble as a dot on a blank canvas. In fact, the dot and the square emerged as the foundational elements shaping his artistic expression very early.

Born in Turin, Italy in 1949, Paolo Colombo now lives and works in Athens, Greece. A key moment in his artistic journey occurred when he was 19, on an extended holiday in Greece. The plan was simple – to fill his suitcase with art and return home to Italy. With paintbrushes, oils and canvases in tow, he spent three months capturing landscapes. However that suitcase was lost and Colombo found himself starting anew, this time with watercolours, pencils and paper. Now, these are the only artistic tools he uses, to ensure he can carry his art with him at all times.

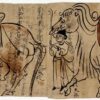

Colombo’s re-encounter with art was as humble as a dot on a blank canvas. In fact, the dot and the square emerged as the foundational elements shaping his artistic expression very early. The dot, he says, is the “start of all things”. Placing a dot on a page was a learning technique, “teach[ing] myself to paint from this first connection of the pencil with a surface”. Colombo remembers his first assignment as a six-year-old at school: he had to mark a dot at the corner of each square on the first page of his maths notebook. The memory of this exercise resurfaced later in life with his desire to study the structure of images and representation by analysing the potential of the most elementary forms.

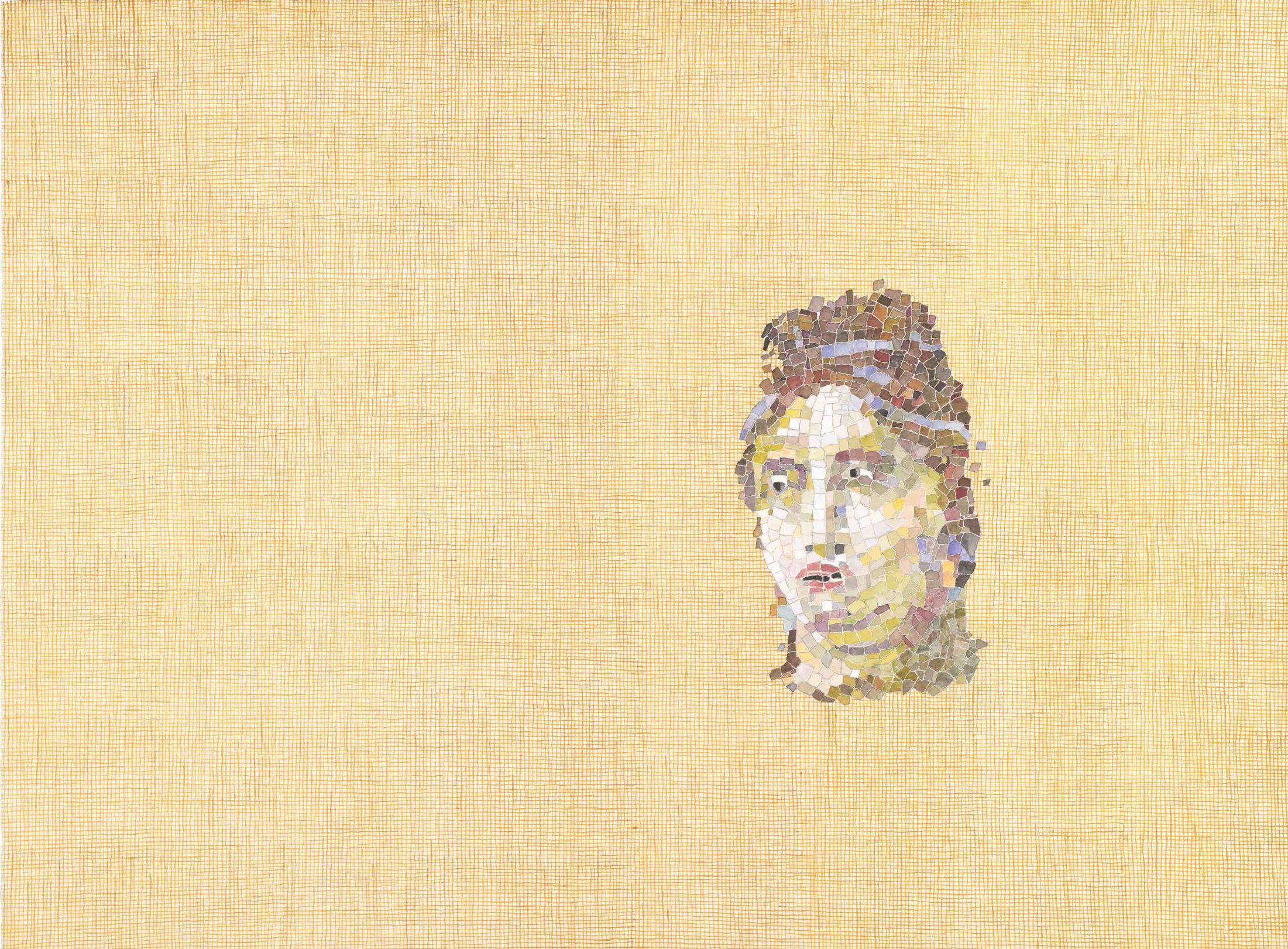

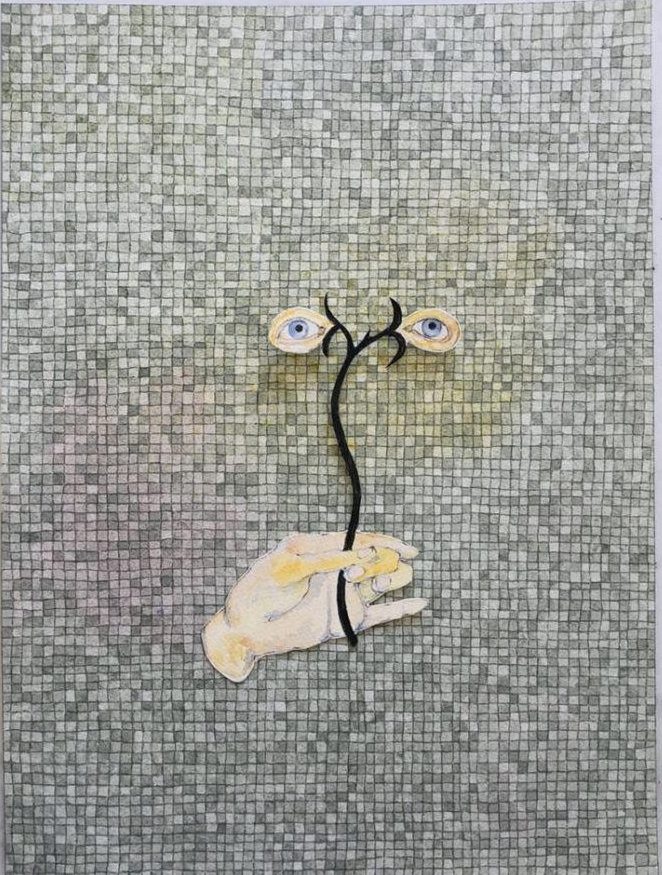

The square references the elegant simplicity found in the mosaic tiles of Classical and Byzantine art, a key influence on Colombo’s creative direction. He wanted his art, he says, “to be sober and austere”, qualities he also associates with mediaeval painting. The motifs of dot and square extend into themes of sacred geometry, which ascribes symbolic and divine meanings to shapes. For example, the square appears in many spiritual traditions, representing stability, balance and order. It is often associated with the physical world and the material aspects of existence.

This emphasis on the amalgamation of the aesthetic and the symbolic highlights the complexity and nuance of Colombo’s practice. Through this fusion of ancient inspiration and contemporary interpretation, Colombo’s art bridges past and present, inviting viewers to reflect on the enduring influences of the oldest artistic styles on the evolution of art history as a whole.

Colombo’s artistic journey paused for 21 years focusing on the responsibilities of raising a family. Although he stayed close to the arts, working in museums and art institutions, he gave up his own art practice. He reflects: “It taught me a lot about working with artists. I can appreciate the other side much better because I’ve been a part of both worlds.”

Colombo’s art is entwined with his daily rhythms. His a part of his life, a source of intimate connection. He finds inspiration in solitude and introspection.

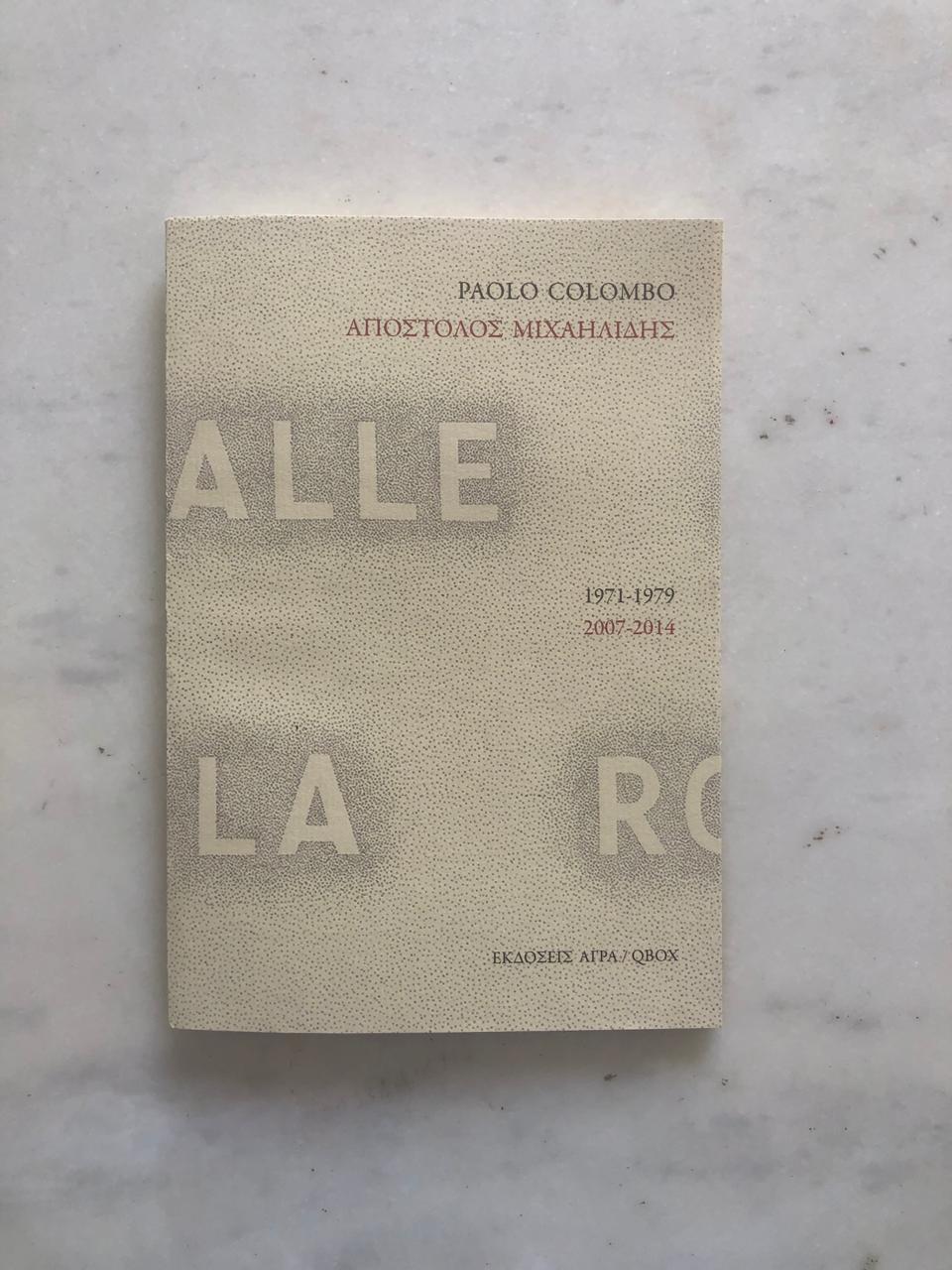

Colombo also has a degree in Languages and Literature from the University of Rome. He writes poetry and has published a collection of his poems from 1971–79 and 2007–14, Apostolos Michailidis. How do Colombo’s poetics relate to his imagery, and vice versa? The last verses of the book read:

“We have to write, we have to write.

And this because of the silence of mosaics,

the silence of statues,

the silence of temples and of columns.

And this is because of the silence of the altars.

It is we the faithful who bear its weight.”

Colombo explains that his painting and writing – are rooted in the world of feeling. The silence of the visual world requires written expression, he says, which is why he frequently adds text to his watercolours. The words he uses are always from his own poems, but they don’t dictate the meaning of the work; he leaves space for the audience to reflect on what resonates most with them. He seeks to make room for the experiences of others by abstracting his feelings, distancing himself from what he has expressed.

Colombo’s art, like his lyrical poems, invites viewers into a realm of understated eloquence; it is an invitation to engage with memory and life transcending boundaries and seeking new forms of expression.

Related Articles

The Magazine

Recent Posts

-

Cultural Diplomacy and Artistic Dialogues: Exploring ‘Beneath the Gaze of the Palms’

Cultural Diplomacy and Artistic Dialogues: Expl... -

The Time is Now: How Artists Respond to the Idea of Time

THE TIME IS NOW: HOW ARTISTS RESPOND TO THE IDE... -

Cultural Crossroads: Stories of Exchange

CULTURAL CROSSROADS: STORIES OF EXCHANGE Januar... -

Colour Series Part IV: Purple

COLOUR SERIES PART IV: PURPLE The colour purple... -

On Embroidery & Motherhood with Iliodora Margellos

On Embroidery & Motherhood with Iliodora Ma...

WANT TO STAY UPDATED WITH ITERARTE LATEST ACTIVITES AND NEWS?

Sign up to our newsletter to be one of the first people to access our new art, learn all about our latest launches, and receive invites to our exclusive online and offline art events.