THE TIME IS NOW: HOW ARTISTS RESPOND TO THE IDEA OF TIME

The passing of time governs us all, it dictates the way we approach decisions we make in our lives, how we record our memories, learn about our planet, the way we tell stories.

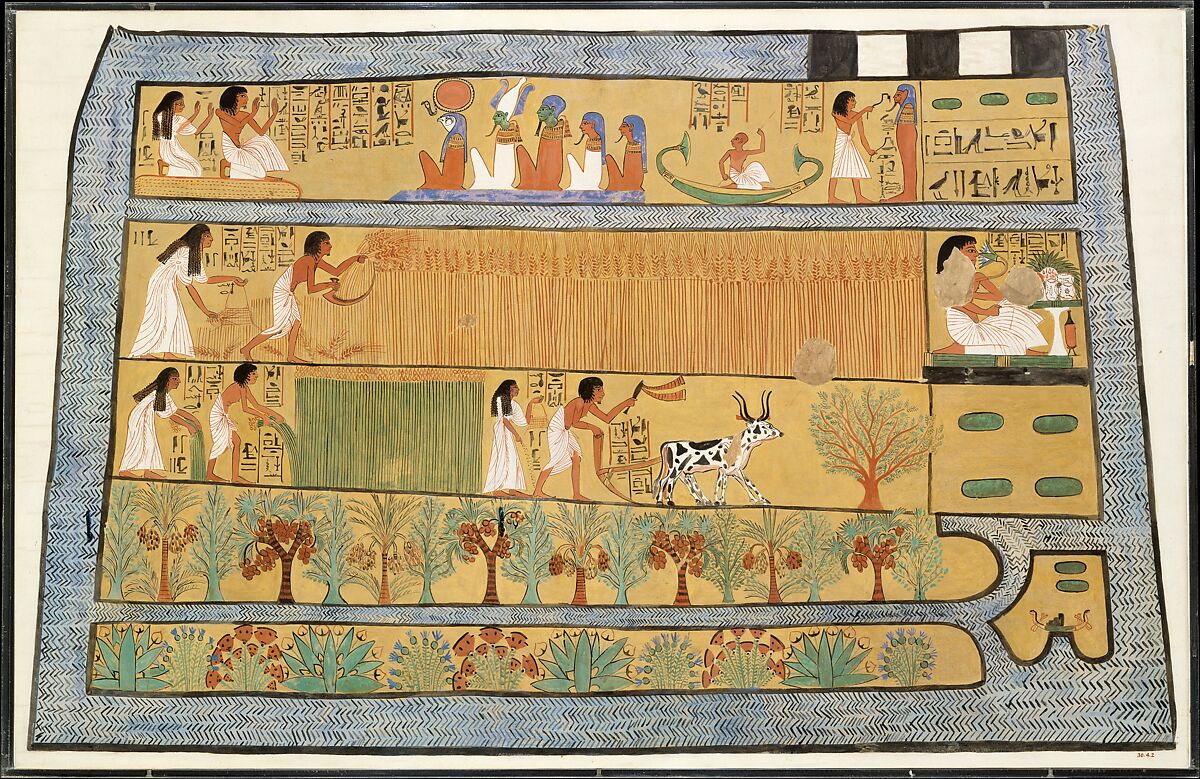

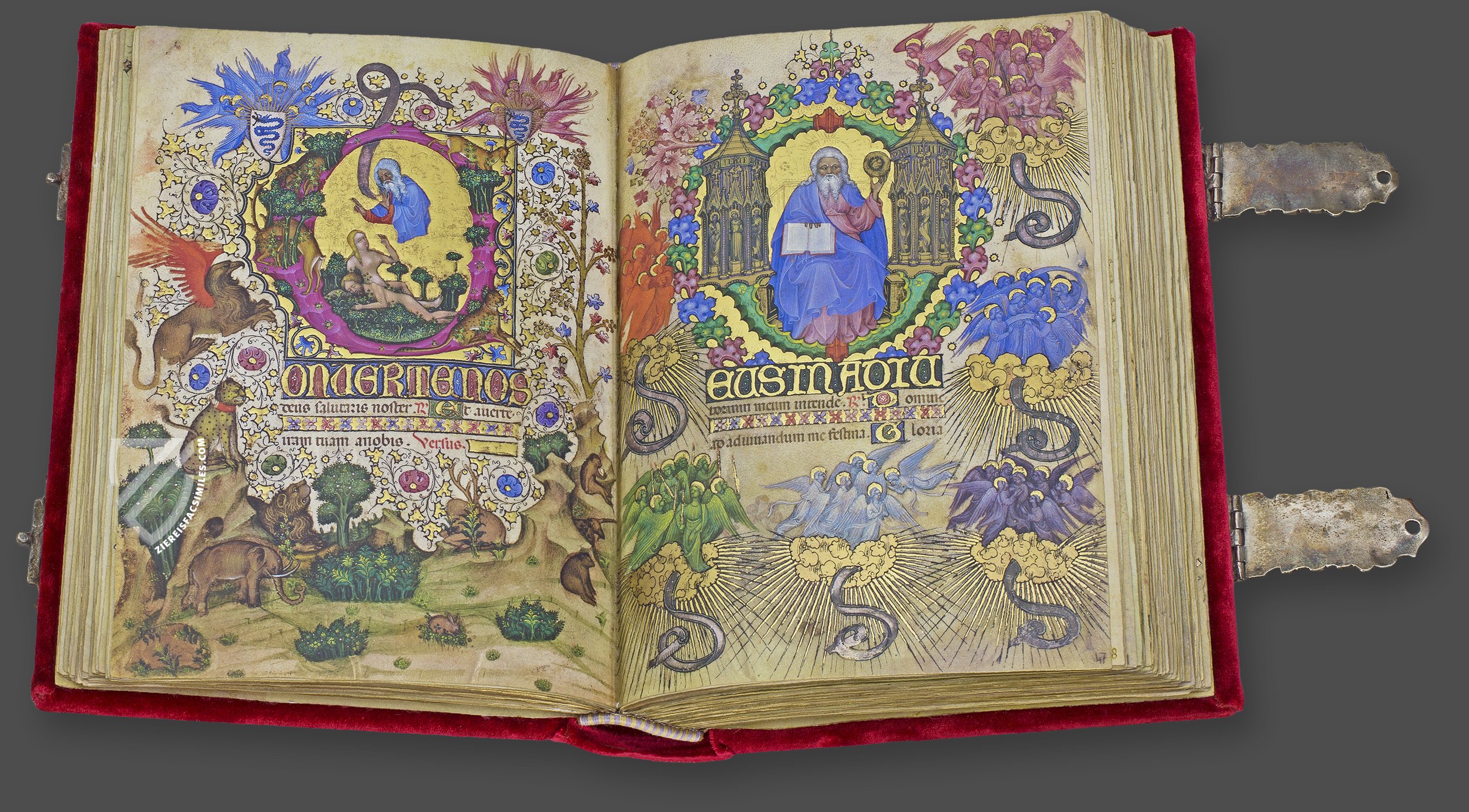

We are accustomed to following the basic construct of linear time – a beginning (the past) an end (the future), and where we live, an in-between space, known as the present moment, which is always moving forward. Digital clocks illustrate this idea, as do narrative paintings from prehistoric caves to Ancient Greek vases. Stories told in stained glass, in medieval manuscripts, the Bayeux Tapestry, all share a linear structure, which continues today in the narratives which frame our everyday experiences, in reality, on the big screen and in our scrolling digital timelines.

Always connected, in the twenty-first century we are rarely unaware of the time of day, as humans we are riddled with complex schedules, filled with anxiety over meeting deadlines, not being late, finishing work on time. The exemplar contemporary take on this is Christian Marclay’s The Clock (2010): a 24-hour long montage, amalgamating extracts from film and television which depict clocks and other references to time. Familiar patterns occur within its narrative such as alarm clocks, mealtimes and appointments, but the most telling message is that even without being acknowledged in the dialogue, clocks are everywhere in modern society.

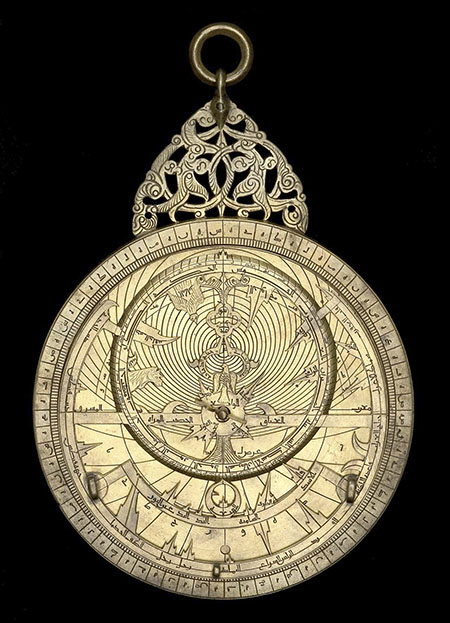

As civilisations progress we have routinely craved systematic order and harnessed our surroundings and shared knowledge to maintain this. The first, most durable time-keeping devices used the movement of light throughout the day to chart the passing of time. Shadow clocks, obelisks and sundials, prevalent from Egyptian times, water clocks by the Babylonians, incense clocks by the Chinese and the hourglass in Europe, used as an aid to measure time at sea. Astrolabes were developed in Persia in the 11th century, as a way of using the stars in the night sky as a navigational aid and calendar. An example on display at the Diriyah Islamic Biennale in Jeddah is the oldest complete geared mechanism in the world.

The earliest calendars date from the Bronze Age, with civilisations such as the Babylonians and Persians being the first to record time using natural cycles including days, lunar cycles (months) and solar cycles (years), utilising the seasons, cosmic cycles across the universe, the rotation of the Earth on its axis.

The Bible follows a linear structure, starting with the creation of the world in Genesis through to the final judgement day in Revelation, due to take place at an indeterminable date in the future. In the meantime, worshippers find structure in their prayer through using objects to help them mark time – such as the medieval book of hours and psalters, rosaries, and through audio queues, such as church bells and the adhan, or call to prayer. In Islam, time is both cyclical and linear, it is a gift from God, and an indeterminable force. In Hinduism, the concept of the afterlife and resurrection bring a further dimension to our understanding of time, not being limited to one lifetime.

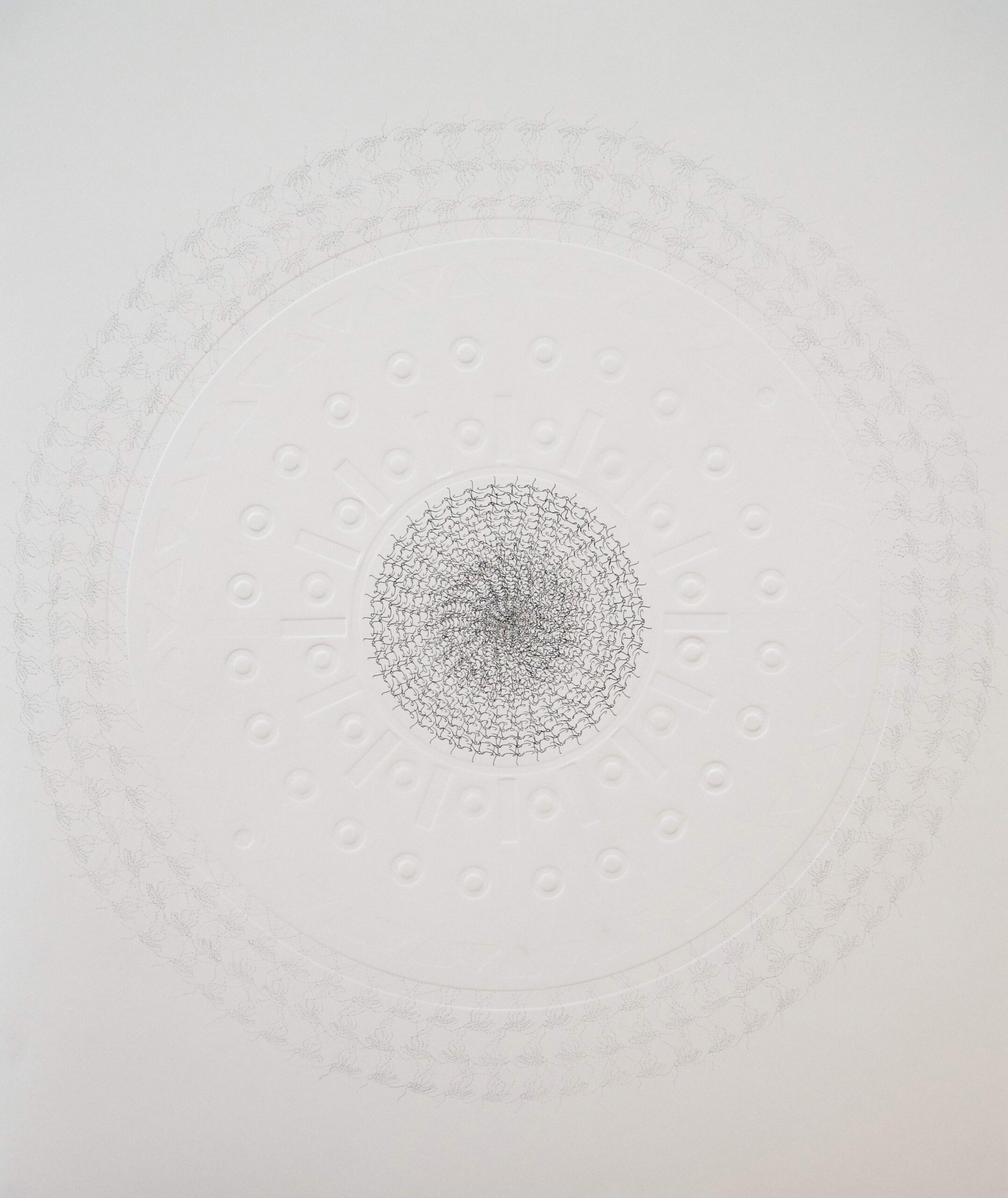

What such cycles reveal is that there is a circularity to time, that the linear structure we are accustomed to repeats. Through devotion, meditation, intense periods of creativity or stillness, we can, it feels, go beyond time, to the infinite.

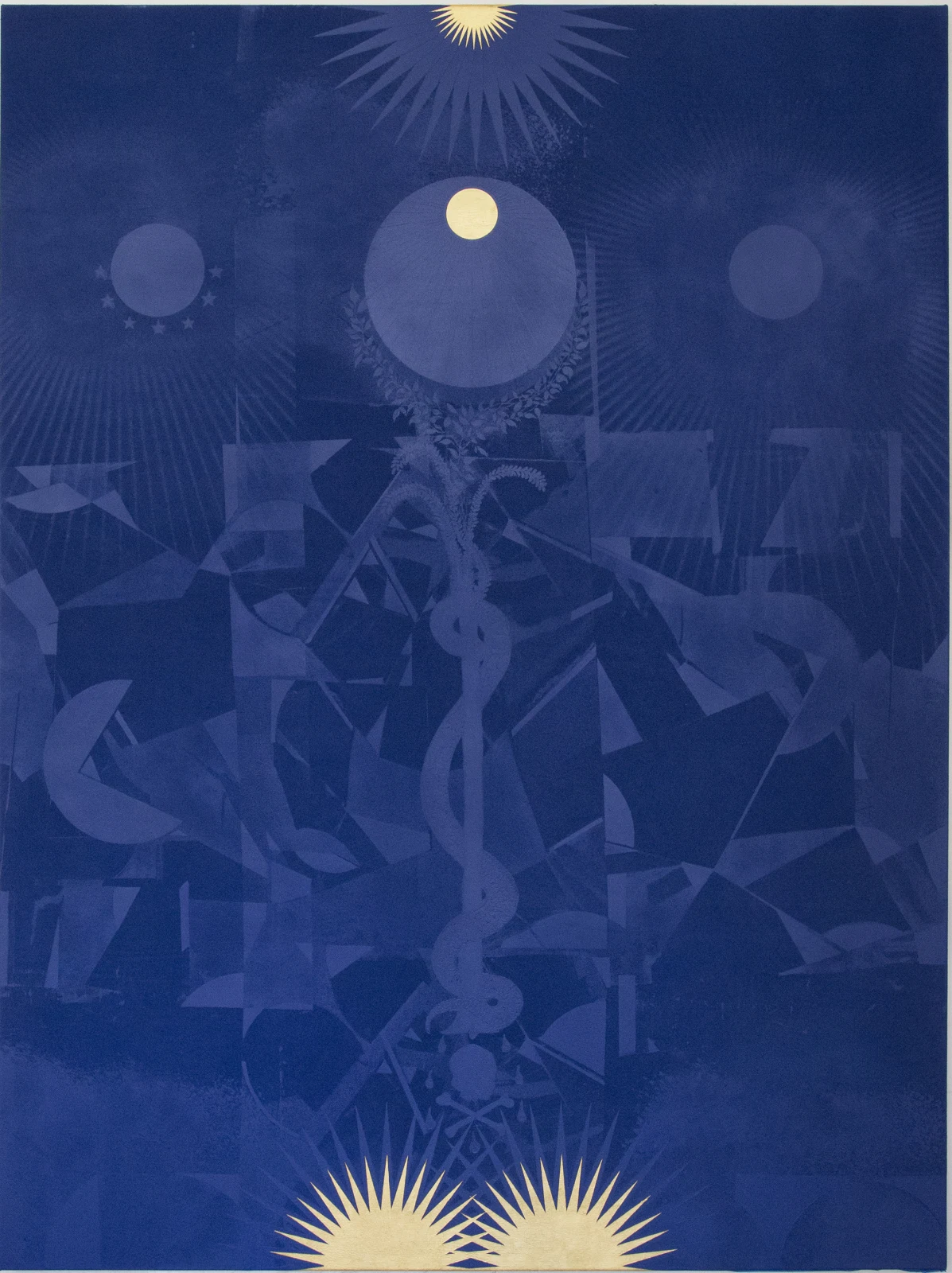

Two ITERARTE artists focus on this in their practice. Through her intricate works on paper and pieces produced through performance, Tazeen Qayyum represents a certain stillness, in pursuit of infinity. Panos Tsagaris takes as his inspiration spiritual practices and mystical traditions of Eastern philosophy, breaking down our idea of time to its very essence, that of our consciousness from darkness to light.

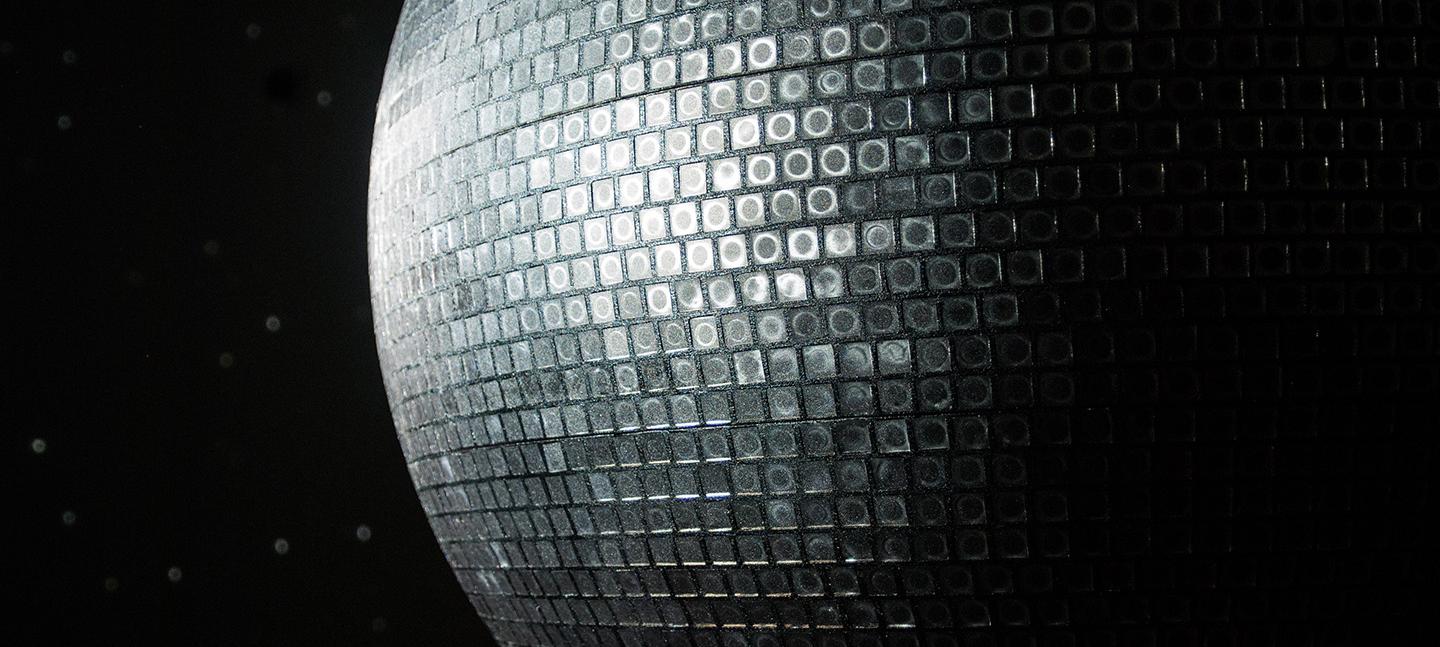

Katie Paterson is an artist who connects with deep time or kairos in her practice, that we are but the current, minimal iteration of a lineage stretching back millennia in terms of geological time frames. Her piece The Moment (2022) is an hourglass filled with star dust, fossilised remnants of a time before the Earth was formed, taken from asteroids and meteorites. Totality (2016) brought together nearly every solar eclipse documented by humankind into a mirror ball of 10,000 individual images, As the World Turns (2010) is a turntable which plays Vivaldi’s Four Seasons over a four-year period, so slow that it is barely audible, Timepieces (Solar System) (2014) is a series of nine clocks that tell the time on the planets in our solar system and Earth’s moon.

Madeline Hollander, an artist, dancer and choreographer, created Sunrise/Sunset (2021) out of 96 recycled car headlights, which she has arranged to become a world clock, turning on and off depending on the real time of their location in the world.

Vikram Divecha, a conceptual artist based in the UAE created a project for Louvre Abu Dhabi that responded to Claude Monet’s series of twelve paintings made at the Gare Saint-Lazare in Paris in the late nineteenth century, one of which is in the collection. The spread of the railways was instrumental in structuring time, until then each town in France maintained local solar time, still measured with a sundial. Following the introduction of Greenwich Mean Time in the UK 1884, Paris Mean Time was adopted in 1891, signalling a shift in time being dictated by nature to prioritising commerce and industrialisation. A twist on this history is that for twenty years from 1891-1911, French railways ran trains five minutes behind schedule to accommodate late comers. For his project, Divecha persuaded SNCF (the French National Railway Corporation) to delay a specific train from Paris to Rouen by five minutes and recorded this small and yet significant and human discrepancy in a large-scale woven installation, the white sections indicative of waiting times on particular platforms during a 24-hour period, an alternative, abstract Marclay clock.

This leniency and freedom of delaying time is not something we feel today. The feeling of anticipation and waiting is nascent in Monet’s paintings: their compositions dominated by the steam created by these new, man-made beasts. This sensibility would be taken a degree further by the Italian Futurists, their ethos was celebrating modern life and the constant change and movement of time. Inspired by techniques such as chronophotography, which captured multiple images of movement in rapid succession, artists such as Giacomo Balla took as their subject the speed and acceleration of vehicles. The futurist movement was abruptly cut short with the onset of World War One when the reality of the devastation inflicted by modern warfare became clear.

We live in our own uncertain and troubled historical moment, thrown as some scientists believe into a new epoch, the Anthropocene, marked by a severe climate crisis and concurrent cataclysmic violence and unpredictable shifts in political power. Artists such as the Otolith Group have developed projects with durational timelines which confront hostile environments. Stéphanie Saadé, uprooted from Beirut due to conflict, creates conceptual projects inspired by her own personal displacement. Accelerated Time was a series in which she would break a vase into ever smaller pieces, reducing it to a chalky white substance, a dust, speeding up a process of physical degradation that would have taken centuries. The result serves as a trace, suggesting that human and object are indistinguishable when made into dust.

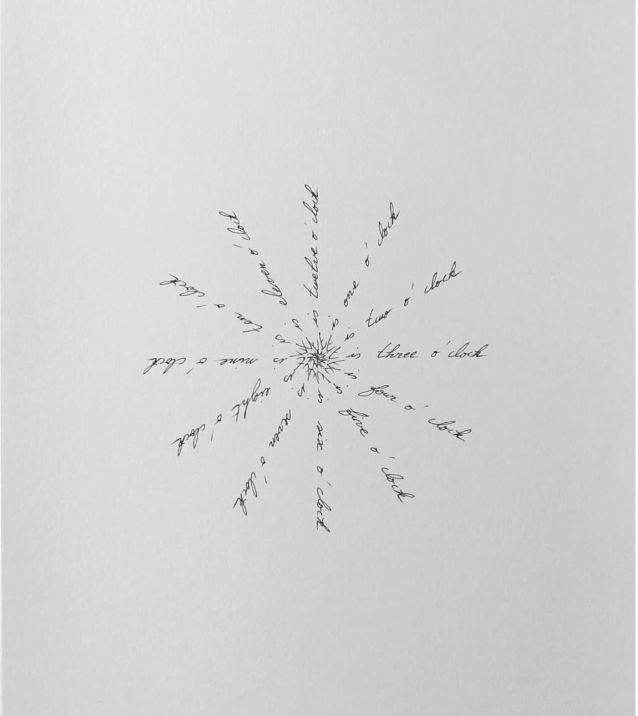

Saadé’s time calligrams are a series of performative works, visual poems, where she writes time as we have learnt to measure it, hours following the hour hand on an analogue clock, minutes and seconds tracing their hands. She merges space and time through constructs we have created.

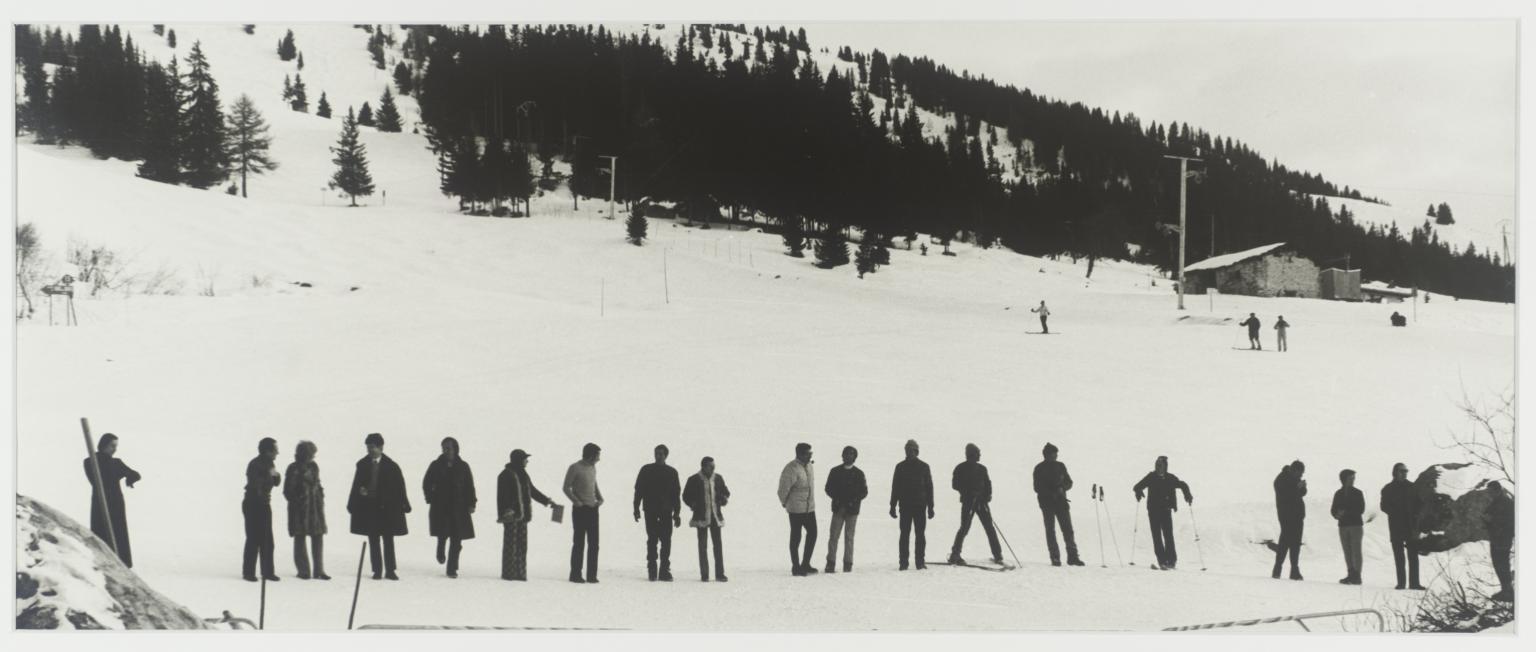

In his series of experimental performances David Lamelas seeks to remove objects from space, leaving only time. In diverse settings, from his native Argentina and the French Alps (illustrated) to the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern, he arranges a group of strangers in a straight line, indicated by a tape on the floor. The first person in line announces the time to their neighbour, who waits sixty seconds before sharing the time with the participant next to them, and so on, until the final person announces the time.

The centrality of humans to this makeshift time-keeping mechanism is crucial, sharing time and space. Throughout art history there has been a more sinister relationship with time, focused on an awareness of our mortality. In 17th century Netherlands, memento mori, still life paintings were prevalent, a genre which signified the fragile and finite temporality of our existence, known as vanitas. Symbols such as the hourglass, distinguished candle, books, unplayable musical instruments, a skull, bubbles or faded, drooping flowers became the subject matter of painting, overriding religious or historical scenes.

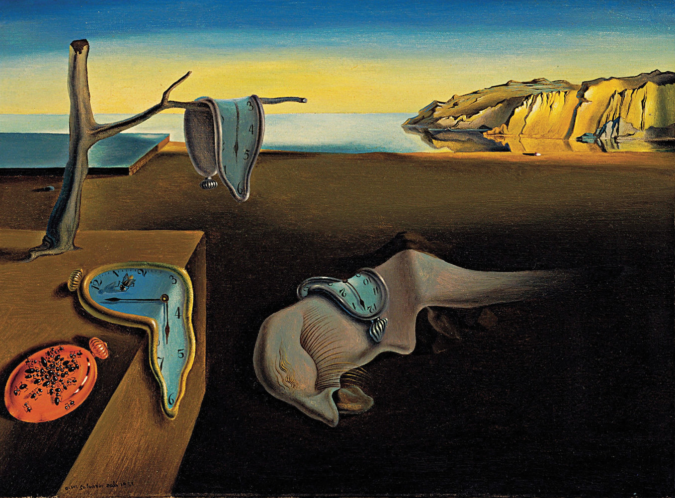

It was not until Salvador Dali’s The Persistence of Memory that the artist attempted to overpower time – or at least its man-made signifier, the clock, by bending and manipulating it, laid out to dry in a barren seascape.

In her photographs, film and performances, Noémie Goudal visualises planetary change over deep time, using geological records, she alludes to the consequences of human activity on Earth, the presence of microplastics in forests and oceans. In Supra Strata, quickly shifting views of a forest and lush vegetation are cast away, we see the artist’s photographic tools, tripod and lights, and witness her pouring acetone over her images – a gesture which vividly reflects our rapid destruction of the planet.

It was Aristotle who first suggested that time is the measure of change. He wrote that different variables can be chosen to measure or harness that change, that none of these has all the characteristics of time as we experience it, but that does not alter the fact that the world is in a ceaseless process of change, for better or worse.

Related Articles

Read more +07 October 2025 By Sibel Moyano in ITINERANT TRAILS

Read more +07 October 2025 By Sibel Moyano in ITINERANT TRAILSA Practice of Resistance: Elif Uras’s Earth in their Hands

The Magazine

Recent Posts

-

A Practice of Resistance: Elif Uras’s Earth in their Hands

Solo Exhibition at Galerist, Istanbul 16 Sept t... -

Textile & Clay: Ancient to Contemporary Testimonies

.... -

Embroidery and Existence: Majd Abdel Hamid on Art and Identity

... -

Material Witnesses Commissions: Afsoon

... -

Material Witnesses Commissions: Lydia Delikoura

...

WANT TO STAY UPDATED WITH ITERARTE LATEST ACTIVITES AND NEWS?

Sign up to our newsletter to be one of the first people to access our new art, learn all about our latest launches, and receive invites to our exclusive online and offline art events.