- Home

- First Principle

- The Sea as a Subject Across Time and Cultures

The Sea as a Subject Across Time and Cultures

The Sea as a Subject Across Time and Cultures

The sea is a powerful expanse of salt water that covers most of the earth’s surface, surrounding all the land we inhabit. And yet it remains a mysterious entity, with positive connotations of exploration and advancement, juxtaposed with uncertainty and danger.

Myths about the sea present it as the pinnacle exemplar of the physical strength of nature, a life-giving and taking force, with several ancient Gods representing water, such as Poseidon and Varuna.

ITERARTE present Marwan Sahmarani’s breathtaking series of expressive paintings, Even When The Water Is Cold (2022), which prompted a study of the sea as a subject and tool for studying human nature throughout art history. Inspired by the landscape of his hometown, Beirut, Sahmarani looks to the water to envision a better reality in his work, as well as revisiting his contemplations about the horizon as a child.

Representations of the sea gained popularity during the 17th and 18th century in Europe, with the rise of naval warfare, as large-scale paintings of ships portrayed imperial prowess. The pivotal turn in the 19th century can be marked by Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa (1819) part of the Louvre collection, Paris, which became an icon of French Romanticism. It radically challenged the conservative tradition of historical painting, instead offering a poetic view of death enhanced by the vicious depiction of the sea.

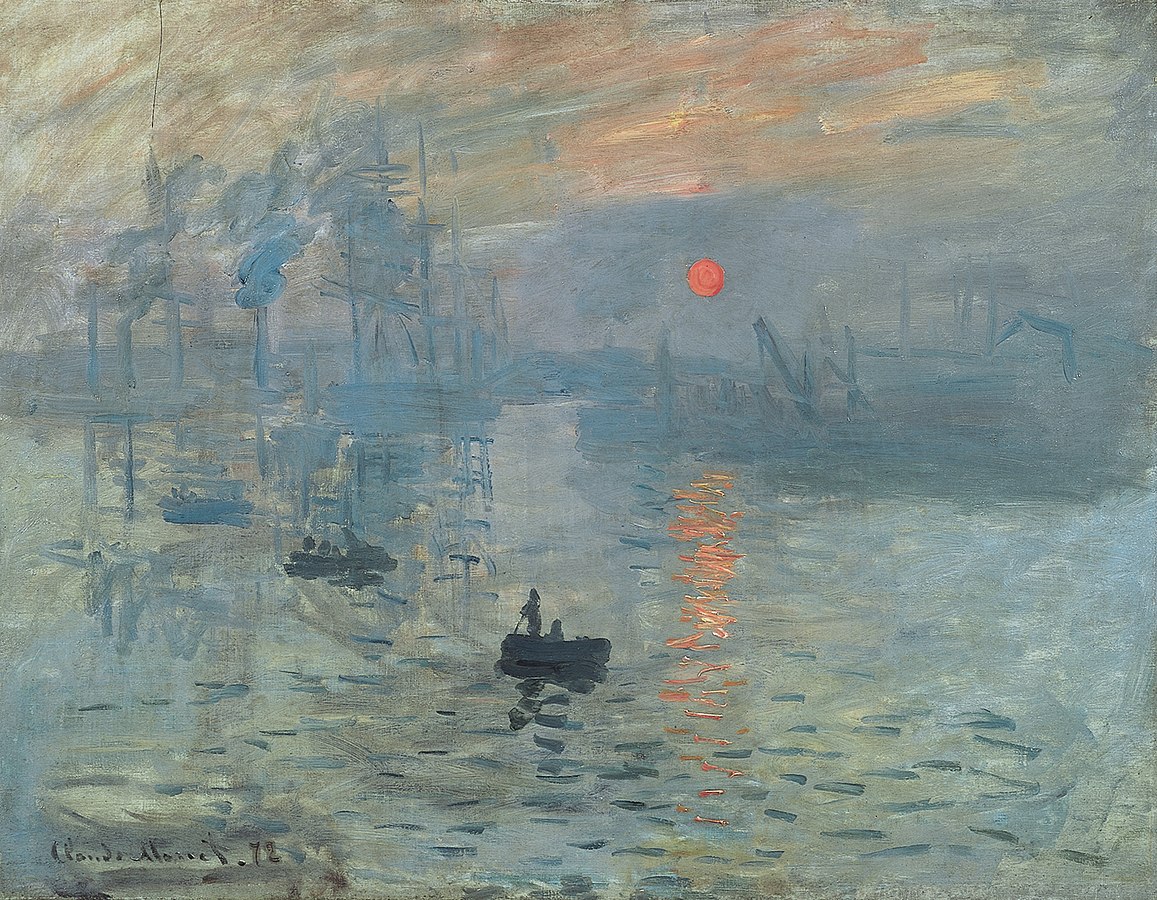

JMW Turner would have seen Gericault's Raft of Medusa when it was displayed in London in 1822, and his unparalleled oeuvre of seascapes took these sensibilities further, softening the edges, depicting pure responses to nature verging on the sublime. Many of the Impressionists, who adopted the plein-air approach, were directly influenced by Turner’s depictions of the sea. Claude Monet’s portrayal of the port in Le Havre in Impression, Sunrise (1872) comes to mind.

The Romantics embraced the beauty and vastness of nature, reflecting the age of exploration in European society. Peder Balke’s paintings of remote Norwegian landscapes merged Romantic interests in natural beauty with dramatic expression, as his muted palette and eerie compositions portray scenes from his solitary travels to the Arctic. His predecessor, Caspar David Friedrich, created The Monk by the Sea (1808-10), showing a small figure against an engulfing wave of water. The monk, who is rendered powerless when confronted with nature, is part of a larger reference made to the evolving relationship between man and God.

At the same time, artists in Japan were using imagery of the sea in their artworks. The iconic Under the Wave off Kanagawa by Katsushika Hokusai (1831) is the emblematic motif of the crashing wave. The recurring imagery of the sea in Japanese woodblock prints is integral to the collective memory of the island nation, which believed the sea held spiritual qualities as well as protecting the land from invasion. From two centuries earlier, Sotatsu’s Waves at Matsushima, bears the distinct characteristics of the ukiyo-e genre and the dynamic movement of water.

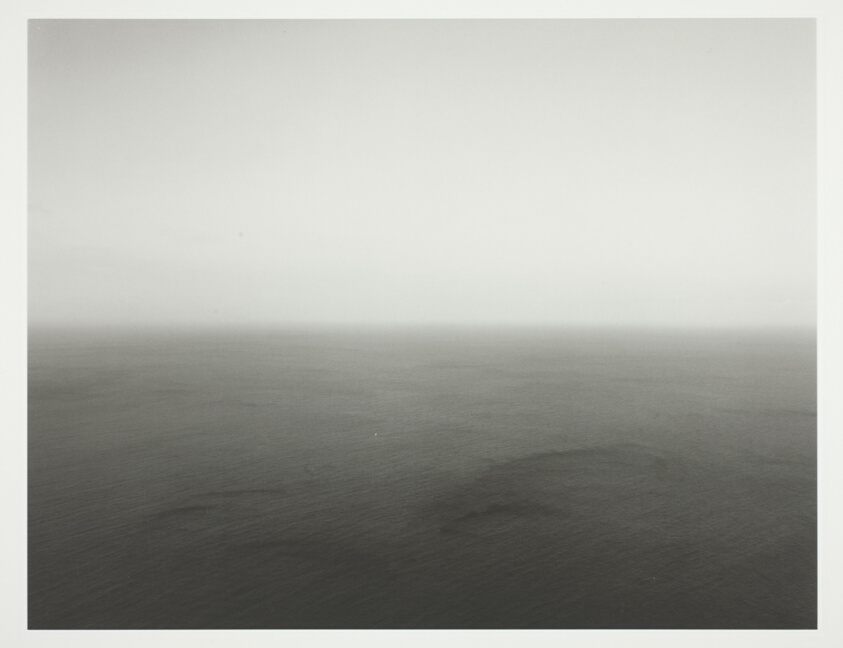

In contrast, contemporary Japanese photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto looks to water as a site of solitude, yet also a significant reminder of human evolution. His Seascapes series presents photographs of horizons in various locations across the world, reflecting on the human need to search for one’s identity and position amongst nature. Raised in Tokyo and now living in California, Sugimoto identifies with the sea more than specific lands that are defined by national boundaries.

Many contemporary artists have used marine imagery to refer to the ongoing political and social catastrophe of the millions of displaced people every year who cross dangerous bodies of sea for better futures. A recent controversial piece by Banksy featured at Glastonbury Festival in June, where an inflatable raft holding dummies of migrants in life jackets was seen moving across the crowd during a performance by the rock band, Idles, probing the lack of compassion across many governments for those escaping conflict.

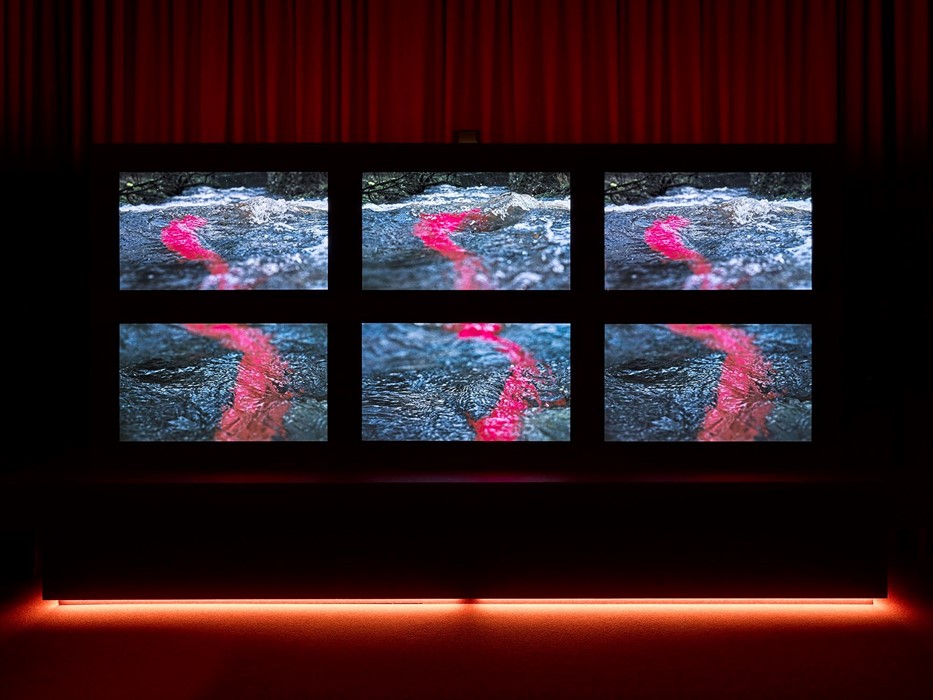

John Akomfrah’s Vertigo Sea is a multi-channel film which premiered at the Venice Biennale 2015, and narrates the sea as a burial ground for exploited and displaced people. Akomfrah connects the topics of colonialism, migration, and climate change by referring to the 1781 Zong Massacre and literary works such as Moby Dick, with water being a poetic meeting point for several temporalities. The theme is further explored in his intoxicatingly captivating British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2024, Listening All Night to the Rain.

Furthermore, the trailblazing painter, Lubaina Himid, has enriched the growing tapestry of Black-British art with paintings positioning black women at the heart of political and historical moments. Between the Two my Heart is Balanced (1991) is a retelling of James Tissot's Portsmouth Dockyard (c.1877), replacing the characters in the original painting with two black women tearing up a map on a boat, thus rejecting the control white men have held over navigation.

Continuing with the theme of migration, we may also consider the positive legacy of the post-war West Indian migrants who came to Britain on HMT Empire Windrush between 1948 and 1971. More than fifty years on, the cultural and economic contributions of the community can be felt, despite the unjust institutional racism that has faced them over the years. Isaac Julien’s multi-disciplinary film installations have constructed powerful narratives of the Caribbean migrant experience; Paradise Omeros (2002) features hazy visions of water recurrently to examine complexities of the Creole identity.

Related Articles

Read more +19 February 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First Principle

Read more +19 February 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First PrincipleCultural Crossroads: Stories of Exchange

Read more +16 January 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First Principle

Read more +16 January 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First PrincipleEditions & Multiples: Art in Repetition

The Magazine

Recent Posts

-

A Practice of Resistance: Elif Uras’s Earth in their Hands

Solo Exhibition at Galerist, Istanbul 16 Sept t... -

Textile & Clay: Ancient to Contemporary Testimonies

.... -

Embroidery and Existence: Majd Abdel Hamid on Art and Identity

... -

Material Witnesses Commissions: Afsoon

... -

Material Witnesses Commissions: Lydia Delikoura

...

WANT TO STAY UPDATED WITH ITERARTE LATEST ACTIVITES AND NEWS?

Sign up to our newsletter to be one of the first people to access our new art, learn all about our latest launches, and receive invites to our exclusive online and offline art events.