- Home

- First Principle

- Shifting the View

Shifting the View

Shifting the View

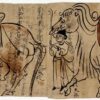

It feels there is a transformation occurring in how we expect to view art in the twenty-first century. Perhaps due to our hyper-connected state with access to all information anytime–many institutions are changing the ways in which we interact and engage with art, encouraging us to look at even the most familiar objects in their collections in new ways. Even a decade ago, it was still the norm to experience art in a pure, ‘white cube’ environment. This has been much critiqued, begun by Brian O’Doherty in a series of essays in Artforum (1976) and subsequently in the publication Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space (1999). It was the ideal aesthetic for modern art which sought to reach total abstraction, for a painting or sculpture to be entirely on its own as a work of perfection, distanced from real life. From the Museum of Modern Art in New York in the 1920s onwards, it has been the chief curatorial choice in museums and commercial galleries globally.

In The UAE, the exhibition In Real Time at the NYU Abu Dubai Art Gallery had a similar concept. An ever-shifting display of work during the exhibition’s three-month run, a lot of which was created ‘in real time’ in the gallery space, including audio pieces, dance performances, installations, fresco murals, and much audience participation, such as a wall drawing by Sol LeWitt.

Things began to change when Tate Modern first opened in 2000, challenging the chronological hang of its permanent collection in favour of a thematic one, its subsequent re-hangs and last year’s significant shift at Tate Britain have reverted back to using artworks to tell historic stories and contexts in a logical sequence. It was important for art to not stand on its own, but be reflective of, and connected to our lives. In 2006, Tate published a conversation ‘Private pleasure for the public good?’ between three museum curators, discussing what they see as being priorities, and more and more institutions are understanding that shaking things up brings the public back. Today such discussions have come to the forefront with scholarship putting as a major priority the rethinking of the nature of display in relation to new audiences and engagement, and the changing roles of artists and institutional staff (see Fatoş Üstek, The Art Institution of Tomorrow, 2024).

This June, the most talked about exhibition that opened concurrently to Art Basel was the summer exhibition at the Beyeler Foundation. With a curatorial team of seven, made up of Sam Keller the Director along with Hans Ulrich Obrist and artists like Tino Seghal, Precious Okoyomon and Philippe Parreno and a partnership with Luma Foundation, its experimental presentation was ever changing – artworks constantly changing, even the title of the exhibition alters frequently, currently it’s called The Lateness of the Hour. Seghal’s controversial curation in particular brought artworks into almost uncomfortably close conversations, a Giacometti staring into a Francis Bacon, or a Brancusi up against a Jeff Koons – canvases actually touching one another and making new configurations, sharing fresh ideas, all the time.

In The UAE, the exhibition In Real Time at the NYU Abu Dubai Art Gallery had a similar concept. An ever-shifting display of work during the exhibition’s three-month run, a lot of which was created ‘in real time’ in the gallery space, including audio pieces, dance performances, installations, fresco murals, and much audience participation, such as a wall drawing by Sol LeWitt.

The Magazine

Recent Posts

-

Cultural Diplomacy and Artistic Dialogues: Exploring ‘Beneath the Gaze of the Palms’

Cultural Diplomacy and Artistic Dialogues: Expl... -

The Time is Now: How Artists Respond to the Idea of Time

THE TIME IS NOW: HOW ARTISTS RESPOND TO THE IDE... -

Cultural Crossroads: Stories of Exchange

CULTURAL CROSSROADS: STORIES OF EXCHANGE Januar... -

Colour Series Part IV: Purple

COLOUR SERIES PART IV: PURPLE The colour purple... -

On Embroidery & Motherhood with Iliodora Margellos

On Embroidery & Motherhood with Iliodora Ma...

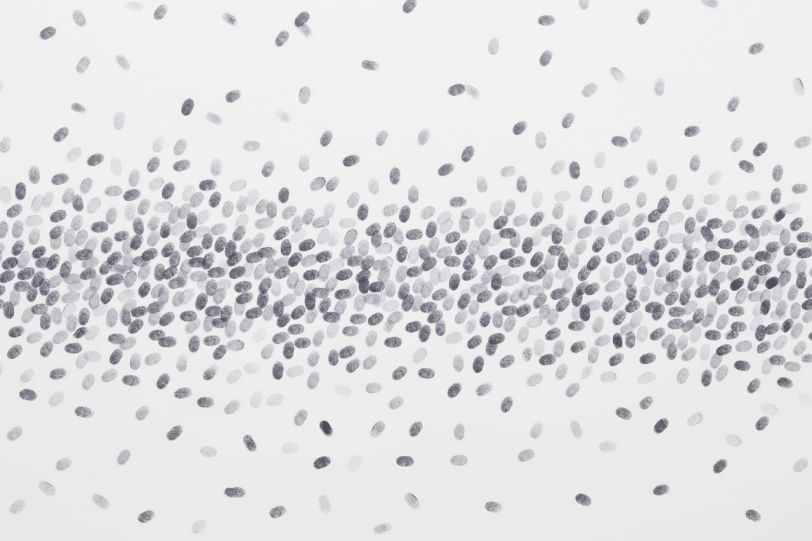

Interacting with artists in person and spending time in the space in which they create is a real coop for most collectors and art appreciators, and usually occurs during a scheduled open studio or an art school degree show, not in a gallery space itself. There was something about showing art in a ‘white cube’ that elevated ‘the artist’ to a god like status – not reachable, not human. Today, it is understood that to know the back story of artists helps with an appreciation of their work. This is something we prioritise at ITERARTE, we know our public will engage more with the art we show by hearing conversations on our podcast series Arteculations, reading our artists responses in our confession’s questionnaires, and be fascinated by gaining privileged access to their camera rolls and playlists. We also think it helps collectors to see artworks displayed in a variety of settings, hence our varied pop-up exhibition programme. Recently we held a private exhibition Wandering Echo in a domestic interior space in Hampstead, London, giving collectors the opportunity to see how artworks can enhance a private space, and interact with design pieces and furniture.

Patrons of art have always commissioned work for their private spaces, take the palazzos of Florence by Renaissance masters for the Medici family, or the Burghers of the low countries. Today art is displayed everywhere around us, but sometimes, the most special experiences can happen at home, with work you have a personal connection with.

Related Articles

Read more +19 February 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First Principle

Read more +19 February 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First PrincipleCultural Crossroads: Stories of Exchange

Read more +16 January 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First Principle

Read more +16 January 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First PrincipleEditions & Multiples: Art in Repetition

Shifting the View

It feels there is a transformation occurring in how we expect to view art in the twenty-first century. Perhaps due to our hyper-connected state with access to all information anytime–many institutions are changing the ways in which we interact and engage with art, encouraging us to look at even the most familiar objects in their collections in new ways. Even a decade ago, it was still the norm to experience art in a pure, ‘white cube’ environment. This has been much critiqued, begun by Brian O’Doherty in a series of essays in Artforum (1976) and subsequently in the publication Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space (1999). It was the ideal aesthetic for modern art which sought to reach total abstraction, for a painting or sculpture to be entirely on its own as a work of perfection, distanced from real life. From the Museum of Modern Art in New York in the 1920s onwards, it has been the chief curatorial choice in museums and commercial galleries globally.

In The UAE, the exhibition In Real Time at the NYU Abu Dubai Art Gallery had a similar concept. An ever-shifting display of work during the exhibition’s three-month run, a lot of which was created ‘in real time’ in the gallery space, including audio pieces, dance performances, installations, fresco murals, and much audience participation, such as a wall drawing by Sol LeWitt.

Things began to change when Tate Modern first opened in 2000, challenging the chronological hang of its permanent collection in favour of a thematic one, its subsequent re-hangs and last year’s significant shift at Tate Britain have reverted back to using artworks to tell historic stories and contexts in a logical sequence. It was important for art to not stand on its own, but be reflective of, and connected to our lives. In 2006, Tate published a conversation ‘Private pleasure for the public good?’ between three museum curators, discussing what they see as being priorities, and more and more institutions are understanding that shaking things up brings the public back. Today such discussions have come to the forefront with scholarship putting as a major priority the rethinking of the nature of display in relation to new audiences and engagement, and the changing roles of artists and institutional staff (see Fatoş Üstek, The Art Institution of Tomorrow, 2024).

This June, the most talked about exhibition that opened concurrently to Art Basel was the summer exhibition at the Beyeler Foundation. With a curatorial team of seven, made up of Sam Keller the Director along with Hans Ulrich Obrist and artists like Tino Seghal, Precious Okoyomon and Philippe Parreno and a partnership with Luma Foundation, its experimental presentation was ever changing – artworks constantly changing, even the title of the exhibition alters frequently, currently it’s called The Lateness of the Hour. Seghal’s controversial curation in particular brought artworks into almost uncomfortably close conversations, a Giacometti staring into a Francis Bacon, or a Brancusi up against a Jeff Koons – canvases actually touching one another and making new configurations, sharing fresh ideas, all the time.

In The UAE, the exhibition In Real Time at the NYU Abu Dubai Art Gallery had a similar concept. An ever-shifting display of work during the exhibition’s three-month run, a lot of which was created ‘in real time’ in the gallery space, including audio pieces, dance performances, installations, fresco murals, and much audience participation, such as a wall drawing by Sol LeWitt.

Interacting with artists in person and spending time in the space in which they create is a real coop for most collectors and art appreciators, and usually occurs during a scheduled open studio or an art school degree show, not in a gallery space itself. There was something about showing art in a ‘white cube’ that elevated ‘the artist’ to a god like status – not reachable, not human. Today, it is understood that to know the back story of artists helps with an appreciation of their work. This is something we prioritise at ITERARTE, we know our public will engage more with the art we show by hearing conversations on our podcast series Arteculations, reading our artists responses in our confession’s questionnaires, and be fascinated by gaining privileged access to their camera rolls and playlists. We also think it helps collectors to see artworks displayed in a variety of settings, hence our varied pop-up exhibition programme. Recently we held a private exhibition Wandering Echo in a domestic interior space in Hampstead, London, giving collectors the opportunity to see how artworks can enhance a private space, and interact with design pieces and furniture.

Patrons of art have always commissioned work for their private spaces, take the palazzos of Florence by Renaissance masters for the Medici family, or the Burghers of the low countries. Today art is displayed everywhere around us, but sometimes, the most special experiences can happen at home, with work you have a personal connection with.

Related Articles

Read more +19 February 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First Principle

Read more +19 February 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First PrincipleCultural Crossroads: Stories of Exchange

Read more +16 January 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First Principle

Read more +16 January 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First PrincipleEditions & Multiples: Art in Repetition

The Magazine

Recent Posts

-

Cultural Diplomacy and Artistic Dialogues: Exploring ‘Beneath the Gaze of the Palms’

Cultural Diplomacy and Artistic Dialogues: Expl... -

The Time is Now: How Artists Respond to the Idea of Time

THE TIME IS NOW: HOW ARTISTS RESPOND TO THE IDE... -

Cultural Crossroads: Stories of Exchange

CULTURAL CROSSROADS: STORIES OF EXCHANGE Januar... -

Colour Series Part IV: Purple

COLOUR SERIES PART IV: PURPLE The colour purple... -

On Embroidery & Motherhood with Iliodora Margellos

On Embroidery & Motherhood with Iliodora Ma...

WANT TO STAY UPDATED WITH ITERARTE LATEST ACTIVITES AND NEWS?

Sign up to our newsletter to be one of the first people to access our new art, learn all about our latest launches, and receive invites to our exclusive online and offline art events.