PERSIAN POETRY

The Age-Old Entanglement of Visual Art and Literature

“Painting is a poetry that is seen rather than felt, and poetry is painting that is felt rather than seen” – Leonardo Da Vinci

Since the earliest of times, humans have communicated through telling stories. This manifested in both the West and East in verbal storytelling traditions, and grew into being written down and illustrated in differing forms of creative expression, depending on what resources, audiences and levels of literacy were prevalent. In Medieval Europe, images were a powerful device to convey stories in scripture, with sacred scenes depicted in illuminated manuscripts and stained glass windows. During the Renaissance, artists and writers returned to study classical antiquity, and due to the widespread adoption of printing and accompanying rise of literacy rates, word and image came together as powerful tools to educate and inspire.

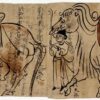

The Persian epic is one of the most significant artforms that came from the region which previously encompassed today’s Iran, Afghanistan, and parts of Central Asia. The epics are usually very long narrative poems composed of rhyming couplets of legendary tales, often retold and exchanged through oral storytelling.

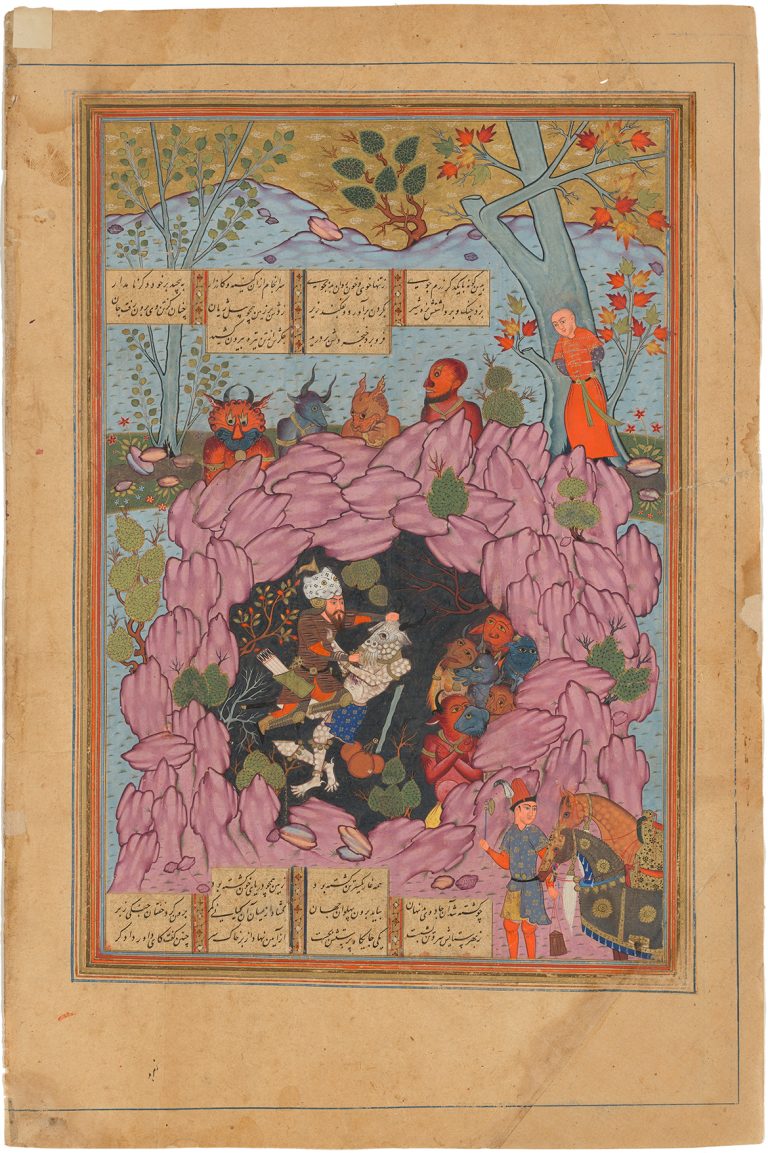

The Shahnameh, written c.940-1020 CE, is the most well-known epic which recounts the ancient history of Pre-Islamic Persia through the reign of 50 kings. It contains 62 stories told in 50,000 verses, which took author Ferdowsi 33 years to complete. The epic is divided into three parts: the mystical, the heroic, and the historical. When it was first circulated, it served as a form of propaganda which exemplified the societal values of modern Persia, including the changing role of women. The Shahnameh continues to preserve the nation’s rich cultural identity and folklore, as well as being a pillar of modern Persian language. Ferdowsi’s impact on subsequent Persian literary culture is comparable to that of Shakespeare.

Many of the stories in the Shahnameh involve defeating evil forces, with kings battling against dragons and demons, demonstrating they are fit to rule. Once the Sasanian empire collapsed due to the rise of Islam in Persia through the Arab invasions, Ferdowsi’s recordings of these historical myths were even more important, and were reproduced in manuscripts evolving into different styles, such as the nasta’liq calligraphy style and versions of the miniature.

Ultramarine became essential for depicting the robes of the Virgin Mary in Renaissance European painting and connoted royalty, pureness, and prestige. Fra Angelico and Giotto would use it in early Renaissance frescoes, where it looked best juxtaposed against gold leaf. This was echoed in manuscript decoration across northern Europe. Artists such as Titian, Raphael and later Vermeer used it frequently to denote the divine, power and wealth.

Another major contribution to Middle Eastern literature was the fairytale collection, The One Thousand and One Nights , which later spread to the West and its stories of Aladdin and Ali Baba depicted in modern art and animated films.

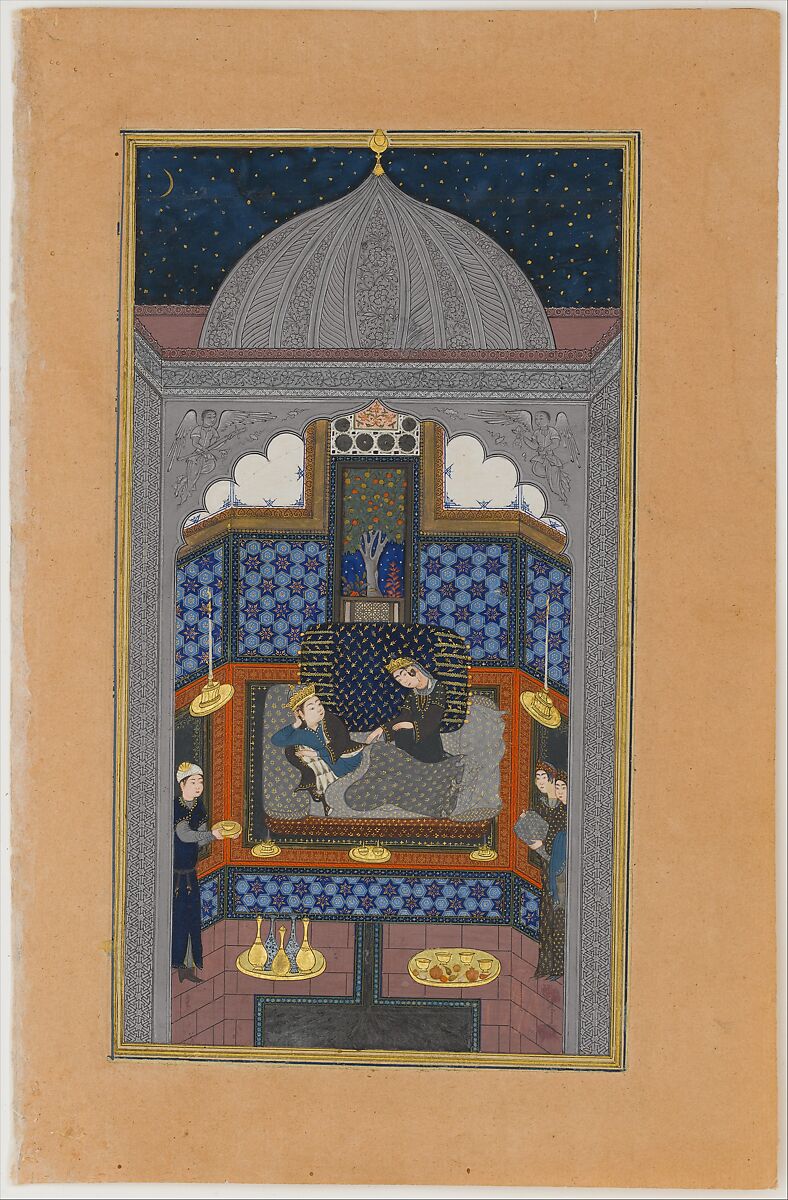

Nizami followed in Ferdowsi’s footsteps to create epic poetry on heroism and mystical characters in the 12th century. Nizami’s Khamsah is a collection of five poems that became popular in the Persian and Mughal Indian royal courts; the poems feature the same characters as the Shahnameh but their content is more focused on love stories and mystic traits in line with the growth of Sufism.

Contemporary art continues to seek classical sources for inspiration, with Persian poetry and other folklore influencing many artists with links to the region. ITERARTE’s own, Afsoon and Maryam Najd, cite the story of the Seven Beauties or Haft Peykar from Nizami’s Khamsah in their explorations of female identity. It is known as one of the most beautiful creations in New Persian poetry for its romantic descriptions:

When morning’s scales had filled with gold

the mountain’s collar, the plain’s robe,

On Sunday, like the sun,

the world- illuming lamp was veiled in gold.

He grasped a golden cup, like Jam;

sun-like, a golden crown put on,

And bound on, like the yellow rose,

his signet ring, amber and gold.

Excerpt from The Haft Peykar (translated by Julie Scott Meisami, Cambridge, 2015)

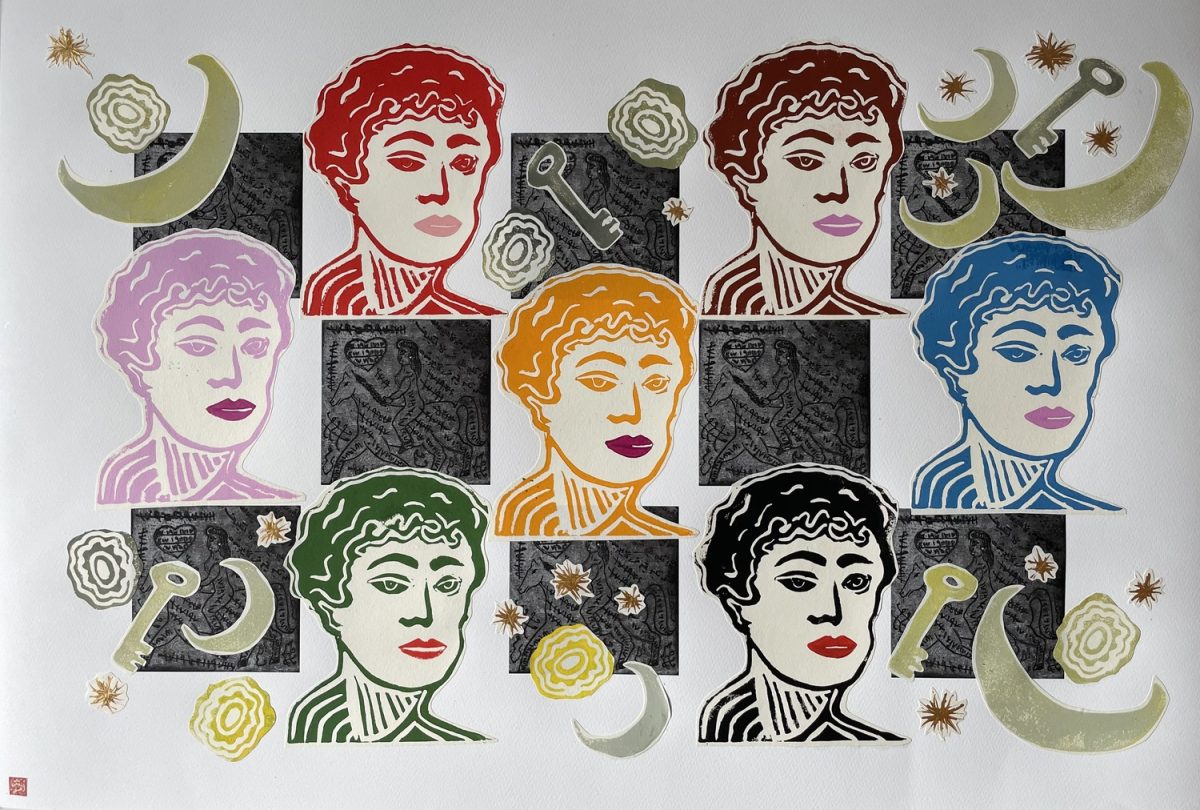

The story of the poem focuses on the Sassanid ruler, Bahram Gur, who falls in love with seven princesses from seven different climes, who are each ruled by a planet. Afsoon’s linocut print, Seven Beauties: Moon and Stars (2023) uses visual elements from the story, with each woman imprinted on the page in their specific colour and surrounded by astrological symbols.

Afsoon is deeply connected to her Persian culture through language, as she refers to the idiosyncrasies of folk wisdom as being integral to her practice. She uses poetry and fairytales to nostalgically reminisce on her childhood in Iran, which was cut short as she was forced to flee during the revolution. Her works exhibit the same mystical storytelling qualities of Persian poetry.

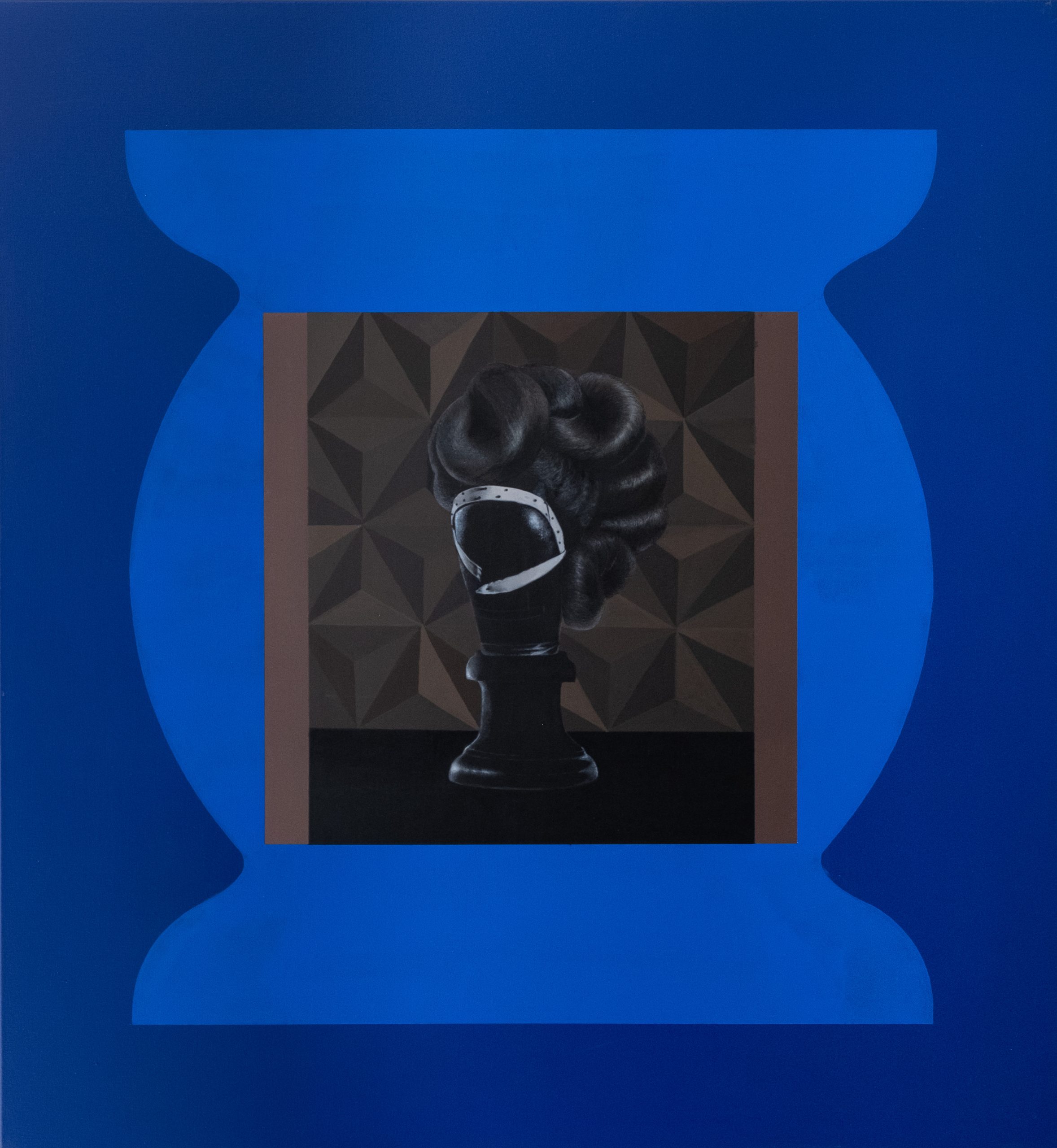

Maryam Najd’s recent exhibition, Seven Shades of Blood, provides a different perspective of Haft Peykar, as she states, “the fight for women’s rights inspired me to create the series.” It is clear that Najd uses the poem to refer to the more sombre features of womanhood, such as the permanence of social discrimination and political oppression, which she has particularly observed in Iran. The artist only reveals their hairstyles while their identities remain hidden, to question the ideas of freedom and censorship in various global contexts.

Each portrait represents the national identities of the women in the poem, encased in geometric shapes in the colour of their specific dome, e.g. Black - India, Blue - Maghrib or North Africa, Sandalwood - China. Najd also refers to the colours for each princess as representing the seven stages of love in Sufi tradition: Attraction, Attachment, Love, Trust, Worship, Madness, Death. The title uses the term ‘blood’ to refer to human genes and heritage that determine physical attributes - defining how each woman is seen and treated in society.

It is clear that the legacy of Persian literature continues to have its impact on art to this day, with various contemporary artists producing new interpretations and reinventing the famous stories and characters from centuries ago. Art has and will always be a tool for storytelling which allows these important pieces of heritage to live on beyond its creators.

Related Articles

Read more +19 February 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in COMPASS

Read more +19 February 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in COMPASSThe Time is Now: How Artists Respond to the Idea of Time

The Magazine

Recent Posts

-

Cultural Diplomacy and Artistic Dialogues: Exploring ‘Beneath the Gaze of the Palms’

Cultural Diplomacy and Artistic Dialogues: Expl... -

The Time is Now: How Artists Respond to the Idea of Time

THE TIME IS NOW: HOW ARTISTS RESPOND TO THE IDE... -

Cultural Crossroads: Stories of Exchange

CULTURAL CROSSROADS: STORIES OF EXCHANGE Januar... -

Colour Series Part IV: Purple

COLOUR SERIES PART IV: PURPLE The colour purple... -

On Embroidery & Motherhood with Iliodora Margellos

On Embroidery & Motherhood with Iliodora Ma...

WANT TO STAY UPDATED WITH ITERARTE LATEST ACTIVITES AND NEWS?

Sign up to our newsletter to be one of the first people to access our new art, learn all about our latest launches, and receive invites to our exclusive online and offline art events.