- Home

- ITINERANT TRAILS

- Colour Series Part I: Blue

Colour Series Part I: Blue

Colour Series Part I: Blue

With over two-thirds of the globe covered in water, and the sky above our heads, the colour blue has confounded artists trying to depict the world we see with tangible materials that we find on the ground.

In wall paintings dating from the 6th and 7th century in Bamiyan, Afghanistan, the semi-precious limestone rock lapis lazuli was first ground into pigment, known as ultramarine.

The stone itself had been popular in Ancient Egypt, on tombs, jewellery and even Cleopatra’s eyeshadow. ‘Egyptian blue’ originated around 3300 BC in Amarna and Memphis, the world’s oldest known synthetic pigment, made relatively cheaply with a hot furnace, much traded throughout the Roman Empire. The only ancient language that had a word for blue was Egyptian – hsbd-iryt, thought to be the original colour of the sky. The Ancient Greeks did not have a word for blue, which is why Homer describes the sea as ‘wine dark’, the sky as ‘bronze’ and dawn as ‘rosy-fingered’, which is discussed in the chapter ‘Oceanic States’ in a new publication The Other Side by Jennifer Higgie. Glazes on Egyptian faience was frequently of a blue tone, such as pyxis, or vessel, from Northern Syria, produced 750-700 BC. For centuries it was imbued with ideas of mystical properties, becoming more valuable than gold, and an important commodity transported on the Silk Road.

It is often assumed that blue and white ceramics originated from the Far East, however blue glazing first became popular in Middle Eastern ceramics in the 9th and 10th centuries, and only spread eastwards to China along the Silk Road and became refined as Chinese porcelain in the Yan (1271-1368) and Ming (1368-1644) dynasties.

India was the major centre for indigo dye production, though it was also cultivated in southeast Persia, in the Kirman area, becoming known as rang-i-Kirmani (‘colour of Kirman’). Persia was also a major source of cobalt ores (sang-i-lajavard), literally ‘blue stone’, and was often used to cover portable objects, as an imitation of the more precious and expensive lapis lazuli. It appears frequently in tiling, for example.

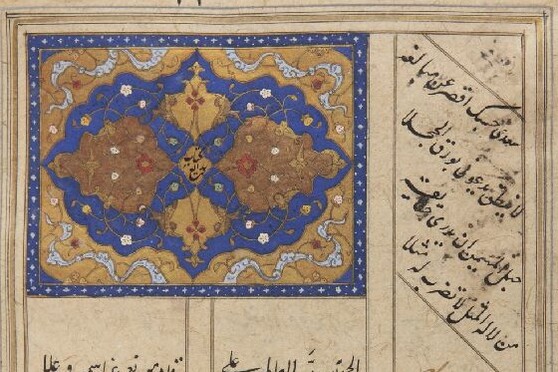

Where we see most evidence of the use of indigo is however in miniature painting, especially from Persia between the 14th and 15th centuries. Artists from the Timurid dynasty painted beautiful images in watercolour, with sharp lines and vivid colours, while Muslim artists oscillated between figuration and abstraction. The Mughal empire hired artists from different backgrounds to work together to produce an extraordinary artistic output.

Ultramarine became essential for depicting the robes of the Virgin Mary in Renaissance European painting and connoted royalty, pureness, and prestige. Fra Angelico and Giotto would use it in early Renaissance frescoes, where it looked best juxtaposed against gold leaf. This was echoed in manuscript decoration across northern Europe. Artists such as Titian, Raphael and later Vermeer used it frequently to denote the divine, power and wealth.

Explored in When We Cease to Understand the World by Benjamín Labatut, ‘Prussian Blue’ was discovered by chance in 1782 by Johann Jacob Diesbach in Switzerland – giving artists the first modern, affordable synthetic pigment – to which Carl Wilhelm Scheele stirred in sulfuric acid creating cyanide, ‘the most potent poison of the modern era’. ‘The blues’ has always been connected to moments of melancholy – Picasso’s blue period from 1901-04 was triggered by the suicide of his friend and Carles Casagemas and his subsequent depression and low psychological state.

Conversely, Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc were so taken with the spiritual connections they found with the colour blue that in 1911 they founded the Blaue Reiter, a group of artists bringing together high and folk art, music, theatre, and painting. In the mid-Twentieth Century, abstract art reached an extreme of monotone through the work of Yves Klein, who’s ambition was always to depict the blue sky in his paintings, in May 1960, registering the paint formula International Klein Blue (IKB) at the Institut National de la Propriété Industrielle (INPI), using it in over two hundred blue monochrome paintings.

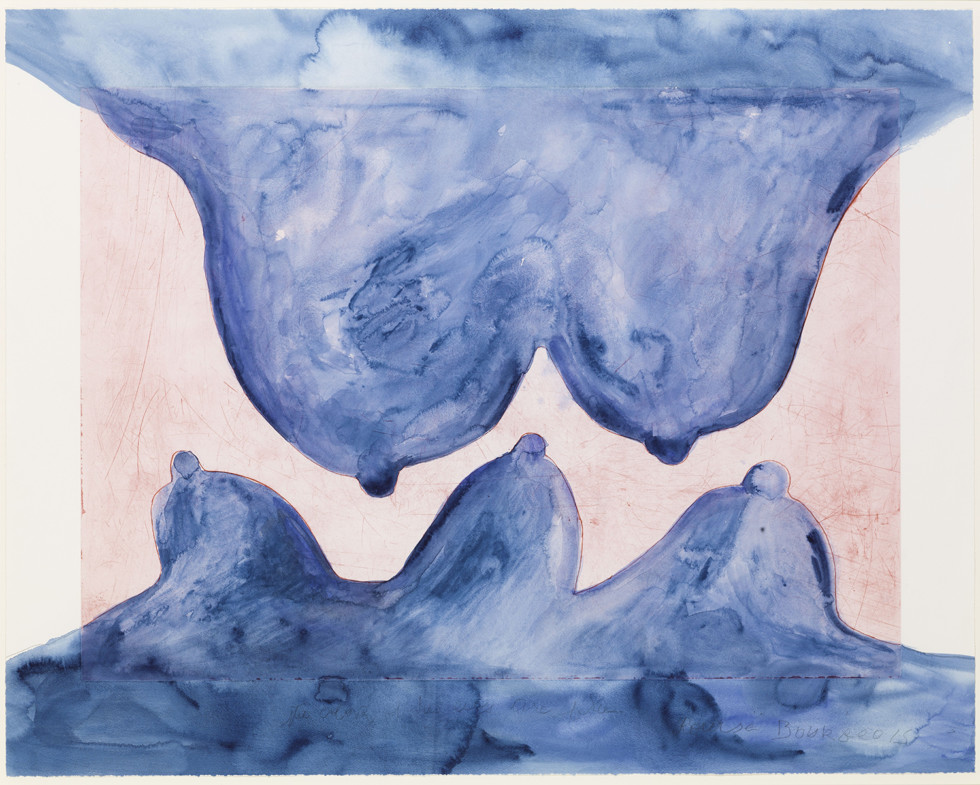

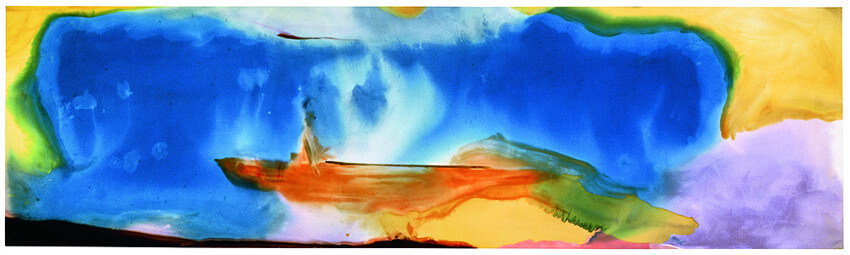

Helen Frankenthaler, an American abstract painter, invented the technique ‘soak-stain’, pouring acrylic paint onto an un-primed, un-stretched canvas, giving freedom to the colours to find a direction of their own.

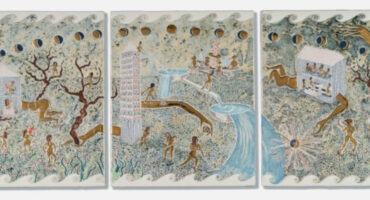

As we turn to study ITERARTE artists which use the colour blue, such as Marwan Sahmarani’s body of work Even When the Water is Cold and Feleksan Onar’s Blue, we see their direct inspiration from the sea of the Mediterranean – for Sahmarani as a swimmer, for Onar from a sailboat – both observing the ever-changing kaleidoscope of hues that form part of nature’s canvas.

Related Articles

Read more +07 October 2025 By Sibel Moyano in ITINERANT TRAILS

Read more +07 October 2025 By Sibel Moyano in ITINERANT TRAILSA Practice of Resistance: Elif Uras’s Earth in their Hands

The Magazine

Recent Posts

-

A Practice of Resistance: Elif Uras’s Earth in their Hands

Solo Exhibition at Galerist, Istanbul 16 Sept t... -

Textile & Clay: Ancient to Contemporary Testimonies

.... -

Embroidery and Existence: Majd Abdel Hamid on Art and Identity

... -

Material Witnesses Commissions: Afsoon

... -

Material Witnesses Commissions: Lydia Delikoura

...

WANT TO STAY UPDATED WITH ITERARTE LATEST ACTIVITES AND NEWS?

Sign up to our newsletter to be one of the first people to access our new art, learn all about our latest launches, and receive invites to our exclusive online and offline art events.