- Home

- Itinerant Trails

- Highlights of the Venice Biennale 2024

Highlights of the Venice Biennale 2024

Highlights of the Venice Biennale 2024

Art can no longer just be viewed (if it were ever possible) in a vacuum or white cube, it must relate to the world around us, and no more so is that the case than with this year’s bumper biennale in Venice, curated by Adriano Pedrosa, Artistic Director of the São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP). The title Foreigners Everywhere, after a work from the Sicilian artist duo Claire Fontaine (themselves named after a well-known French stationery brand), are words found spread across the exhibition in different coloured neon lights, in a variety of languages, in common use and extinct. The title produces a framework of otherness – those differences which can be due to geography, nationality, or ethnic group but also gender, sexuality, and opportunity – that create boundaries and friction between groups of people the world over. A biennale can only ever happen after the ones that have taken place before it – and this edition certainly reaps the benefits of dedicated spaces to historic, overlooked artists from outside traditional centres, as Cecilia Alemani instigated in her curated edition of the Venice Biennale The Milk of Dreams in 2022. Many themes we are exploring in ITERARTE are present in Venice – from maps to mosaics, displacement and diaspora, craftsmanship, collaborations and storytelling.

There was a conscious effort to include artists who have never participated in an international exhibition before, so ripe for new discoveries. Pedrosa divided his exhibition into dedicated sections ‘Nucleo Storico’, gathering works from the twentieth century from across Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America, divided into rooms such as portraits, abstractions, and Italian artists from the diaspora. There is a large proportion of work in textiles throughout this section.

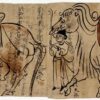

The ‘Nucleo Contemporaneo’ part displays work by 110 artists, broken down further into subjects: the queer artist, the outsider artist, the self-taught artist, the folk artist, and the indigenous artist. It is here we find monumental works by great masters from across the globe, such as Pacita Abad from the Philippines, Aref El Rayess and Chaouki Choukini from Lebanon, Bhupen Khakhar from India and Teresa Margolles from Mexico, alongside a younger generation of (largely female) artists whose conceptual practices are gaining traction in the international art world, such as Maria Taniguchi from the Philippines, Dana Awartani from Saudi Arabia, Bouchra Khalili from Morocco and Lydia Ourahmane from Algeria. Awartani’s Come, let me heal your wounds. Let me mend your broken bones commemorates historic and cultural sites destroyed by war, ripping, and then darning sections of silk, dipped in herb and spice-based natural dyes used in learning practices. Khalili shows The Constellations Series, the closing chapter of her three-year The Mapping Journey Project, studying Mediterranean migration routes through interviews and maps drawn over with permanent marker. Lydia Ourahmane uprooted her rented apartment in Algiers to Venice.

Other highlights include Omar Mismar, who reconfigures scenes from mosaics in the archaeological museum in Syria, reflecting the destruction wrought on the country’s cultural sites, inserting images found on social media and objects such as blankets which are a signal of displacement and desire for comfort. River Claure presents constructed portraits, magical landscapes and docufiction photographs offering a sensitive portrait of contemporary Bolivia. Aydee Rodríguez López similarly makes visible Black communities in Mexico. Bordadoras de Isla Negra is a group of self-taught women who embroidered their stories of daily life in their coastal village in Chile, creating a monumental textile initially commissioned for the United National Conference on Trade and Development in 1972. Güneš Terkol is one of four Turkish female artists in the main exhibition, her fabric banners produced in workshops with women across communities worldwide. Such acts serve as signifiers of the potential for art to connect, rather than to exclude.

The biennale includes twenty artist ‘collectives’ or duos - more than it ever has, along with being the most diverse to date as regards countries of origin (as many as 70), gender and age (around 55% are deceased, through to many millennials). The curatorial feat of Pedrosa’s in bringing together over 350 artists in one cohesive exhibition is astounding - and when set alongside a plethora of national participations and collateral exhibitions across the city, as ever, the Venice Biennale is truly a marvellous showcase of the scope of art production and appreciation today.

Related Articles

The Magazine

Recent Posts

-

Cultural Diplomacy and Artistic Dialogues: Exploring ‘Beneath the Gaze of the Palms’

Cultural Diplomacy and Artistic Dialogues: Expl... -

The Time is Now: How Artists Respond to the Idea of Time

THE TIME IS NOW: HOW ARTISTS RESPOND TO THE IDE... -

Cultural Crossroads: Stories of Exchange

CULTURAL CROSSROADS: STORIES OF EXCHANGE Januar... -

Colour Series Part IV: Purple

COLOUR SERIES PART IV: PURPLE The colour purple... -

On Embroidery & Motherhood with Iliodora Margellos

On Embroidery & Motherhood with Iliodora Ma...

WANT TO STAY UPDATED WITH ITERARTE LATEST ACTIVITES AND NEWS?

Sign up to our newsletter to be one of the first people to access our new art, learn all about our latest launches, and receive invites to our exclusive online and offline art events.