- Home

- First Principle

- Cultural Crossroads: Stories of Exchange

Cultural Crossroads: Stories of Exchange

CULTURAL CROSSROADS: STORIES OF EXCHANGE

January 2025 marked the opening of the second Islamic Arts Biennale in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, organised by the Diriyah Biennale Foundation. Taking its title from a repeated verse in the Quran, And all that is in between, the event showcases more than 500 historical Islamic objects and contemporary artworks. It runs at the Western Hajj Terminal until 25 May 2025. The AlMadar section features objects loaned from over thirty international institutions across twenty countries, presenting the plurality of Islamic visual art and civilisation. Though in tune with the cross-cultural element of other established biennials, among the participating institutions is the Vatican Library, standing out as a particularly remarkable and unexpected collaboration.

The Vatican Library’s participation, which includes the loan of eleven significant works to the Biennale, was informed by the institution's desire to “heal the present from the wounds of hatred and division”. This gesture is especially notable due to the absence of diplomatic relations between Saudi Arabia and the Vatican City, with the former’s position only recognising Islam as an official religion, making the collaboration a powerful symbol of cultural diplomacy and mutual respect.

This event is not the first of its kind - for example, cultural objects played a significant role in the easing of tensions during the Cold War, when the People’s Republic of China organised an archaeological exhibition in the US to improve their diplomatic relations. Such gestures of soft power can be truly significant in bonding together diverse societies.

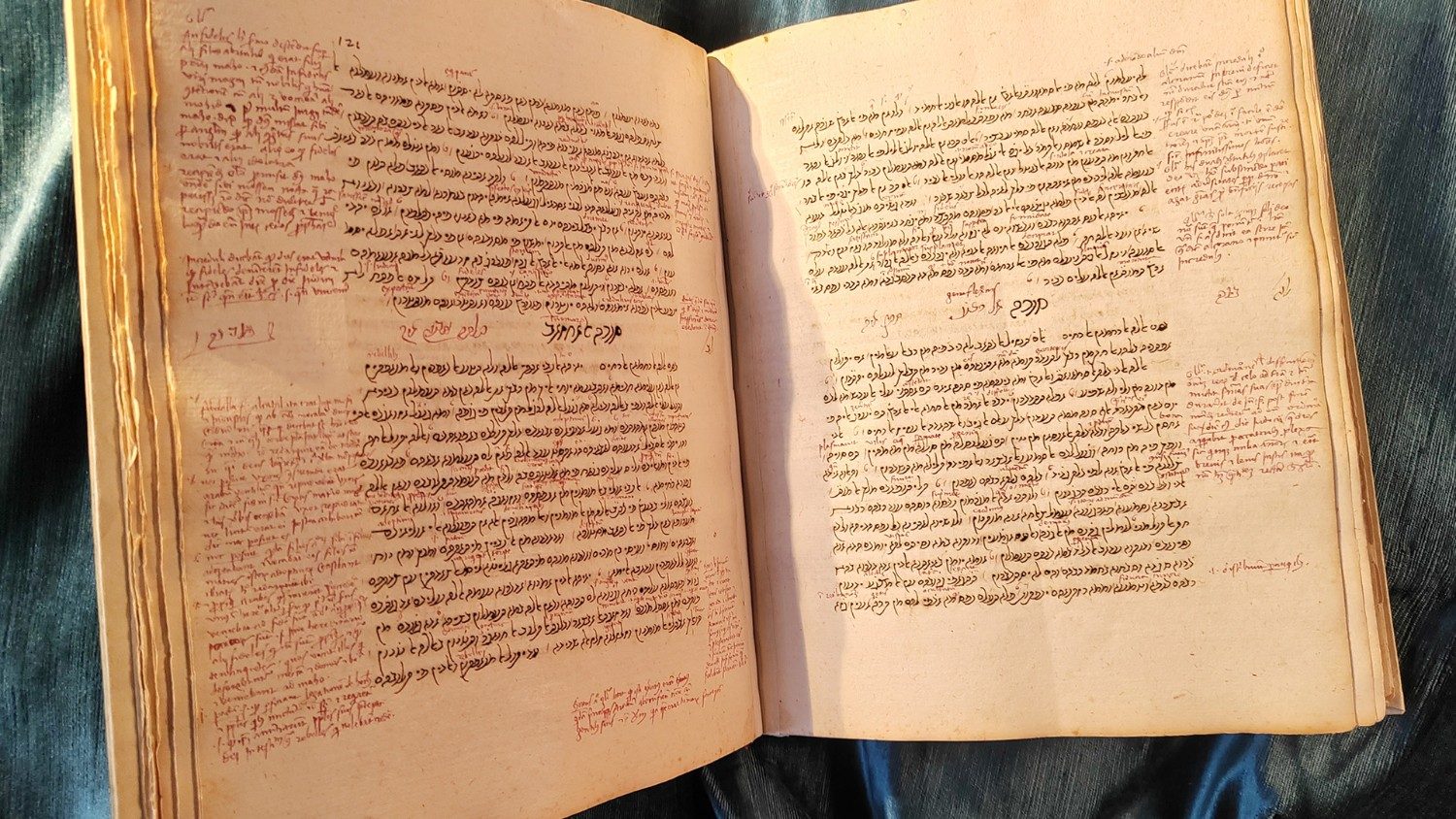

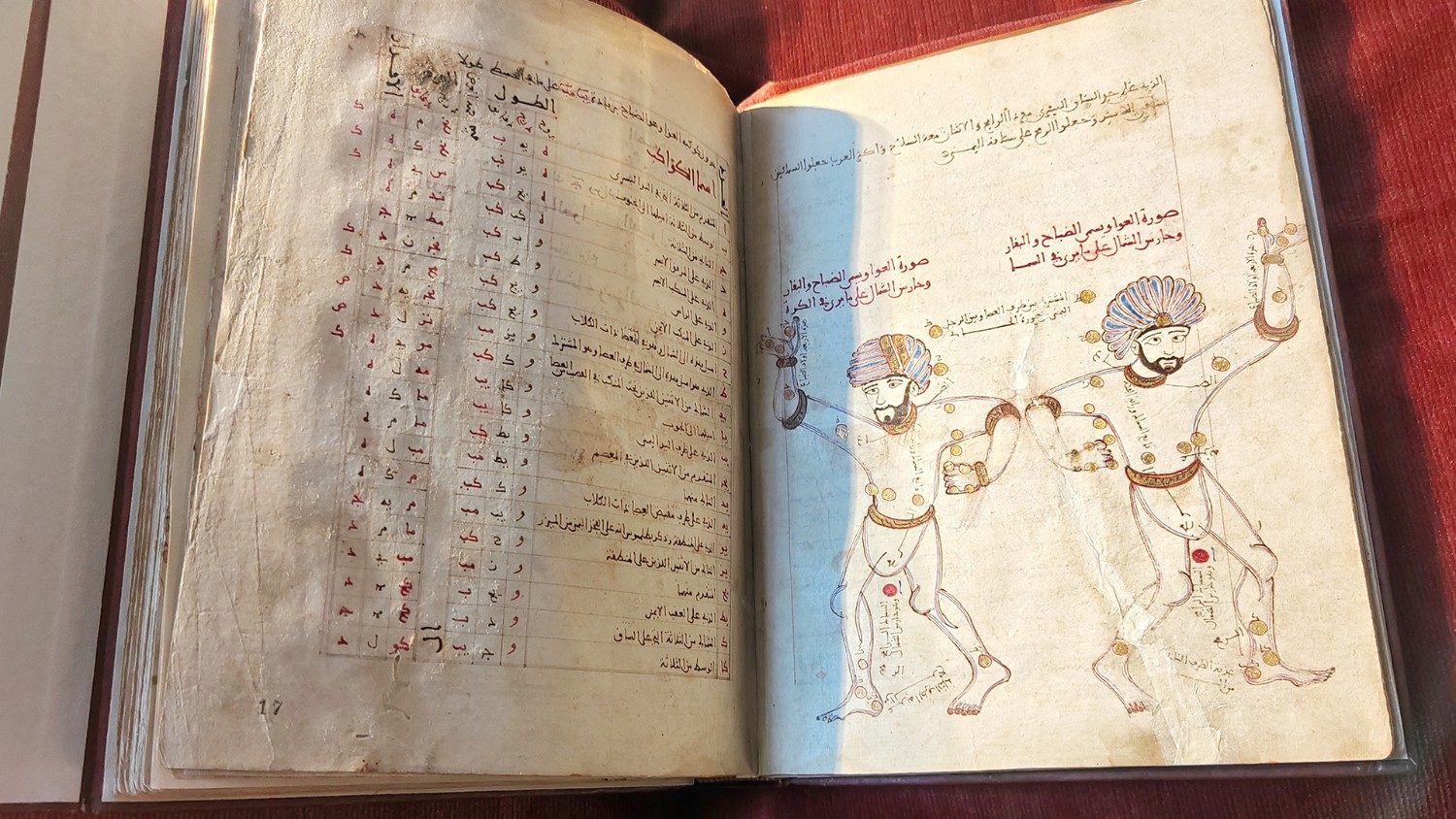

Among the Vatican’s contributions are rare and historically significant manuscripts, such as a 14th century Hebrew translation of the Quran produced in Sicily and likely brought to Rome by converted Jew Flavius Mithridates. This text, later used by intellectuals to study Arabic, features annotations in Latin, highlighting the centuries-old exchange of knowledge across languages and cultures. Also on display are medieval Arabic manuscripts on astronomy, translated into Greek, which reflect the Islamic world’s role in advancing a field that originated in ancient Greece and Asia. These works not only illustrate the transmission of ideas but also mirror the contemporary collaboration between Saudi and Vatican cultural authorities, echoing intellectual exchanges of centuries past.

The Vatican Apostolic Library is one of the oldest in the world, founded by Pope Nicolas V in 1451 to make documents available to scholars for study. From its very foundation, it was intended as a ‘library of humanity’ (as described by Archbishop Angelo Zani, Archivist and Librarian of the Holy Roman Church) - taking as its central tenet that of humanism, so looked beyond theological Christianity, hence the inclusion of Islamic texts.

Following the Islamic expansion in the 7th century, the relationship between Christians and Muslims was multifaceted - they were either studying and learning from one another or clashing over ideological and territorial differences. In places like Al-Andalus (present-day Portugal and Spain), the two groups lived together side by side, with high-ranking patrons of the Umayyad Empire facilitating social, scientific, and cultural exchange. This period, referred to as the “Golden Age”, saw groundbreaking multidisciplinary advancements and its legacy is still palpable in Andalusian architecture and tradition today.

Early Muslim caliphates also drew inspiration from the visual styles of the Byzantine empire, incorporating elements into their coinage and artistic expression. Centuries later, renowned Ottoman architect Sinan looked to Byzantine churches, such as the Hagia Sofia, in his designs of mosques.

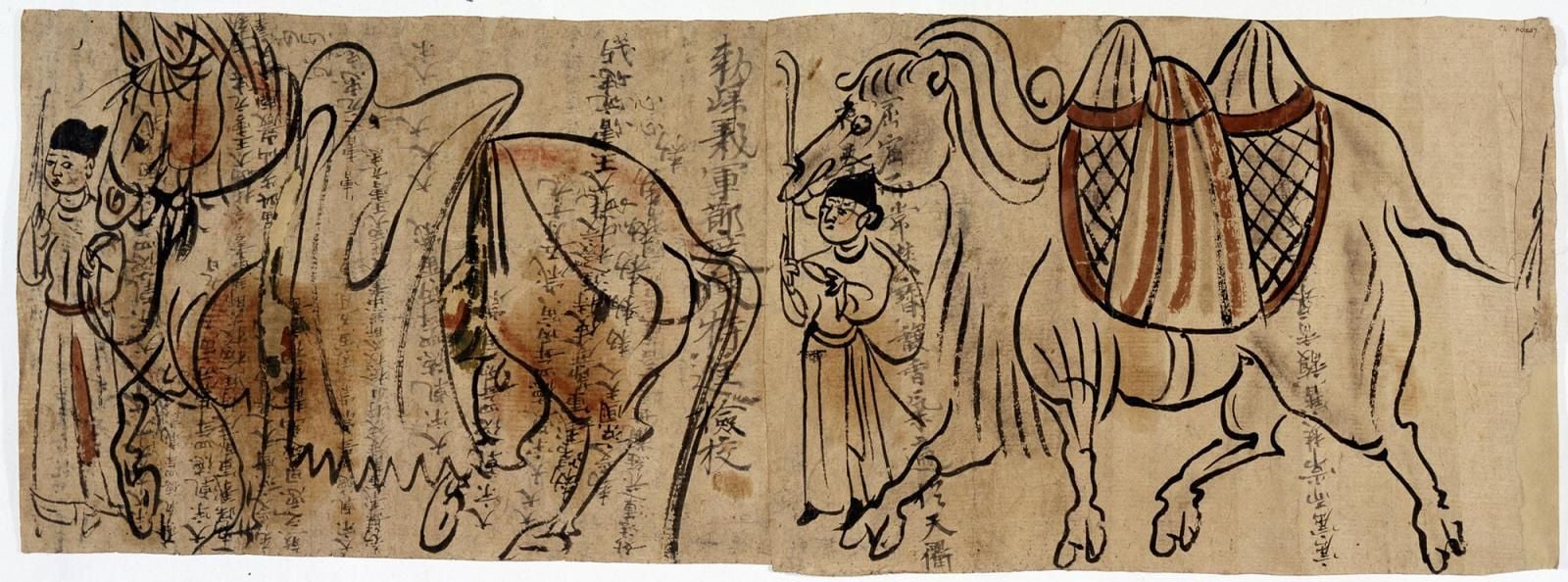

Another exhibition that vividly celebrates the interconnectedness of civilisations is Silk Roads at the British Museum, which tells the well-known story of shared heritage and mutual influence, with a fresh perspective, offering fascinating insights into objects which reveal deep rooted connections across diverse geographies. The exhibition takes visitors on a journey through the period between AD 500 to AD 1000, tracing the vast network of trade routes that stretched from East Asia to Northern Europe. The stunning displays uncover the extraordinary exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures that flourished along these routes.

Silk was far from the only item that spread along these continents - art, religion, and artisanal techniques intermingled and evolved through various routes, shaped by the empires that dominated the era. The exhibition highlights Buddhism’s profound influence on the material culture of regions across Asia, including China and Persia, showcased in the blending of styles in the paintings found in the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang.

The ceramics on display also present the two-way exchange of techniques and motifs between China and the rest of the world. Some ceramics created during the Tang dynasty incorporate Islamic foliage patterns and vibrant colours. Conversely, Islamic bowls often bear a striking resemblance to Chinese sancai (three-colour) ware, demonstrating the dialogue between artistic traditions.

The influence of Chinese art on European culture, a period known as Chinoiserie, is showcased in an exhibition held by the Palace of Versailles at the Hong Kong Palace Museum until 5 May 2025. Focusing on exchanges between France and China in the 17th and 18th century, the exhibition highlighted how artists and intellectuals drew inspiration from Chinese culture in fields such as interior design, literature, music, and painting.

Similarly, the French Romantic painter Eugene Delacroix brought Middle Eastern and North African aesthetics to Europe during the Napoleonic period. Works shown in the Louvre, such as Jewish Wedding in Morocco (1841) and The Women of Algiers (1834) (later imitated by Picasso) are reflective of the Orientalism genre, offering European audiences at the time a glimpse into the Near East. However, while these works captivated viewers with their exoticism, they also encouraged negative stereotypes and at times, served rampant Western colonial expansionist agendas . Description de l’Egypt, the 1809 publication which documented Egyptian life and culture, further fueled the fascination with the region, leading to the blending of Egyptian motifs into French art and design. Its enduring influence was evident in the Art Deco movement that emerged soon after.

A celebration of the resilience and continued relevance in our global contemporary narrative of inter-cultural trade and exchange, Sharjah Biennial 16 (running until 15 June 2025 across the Emirate of Sharjah, UAE) takes as its title ‘to carry’. Its five curators, all women from the global south, created interweaving dialogues between artists of multiple generations, geographies and social contexts. Exquisite venues transformed by Sharjah Art Foundation over recent years offer diverse spaces where artworks live and breathe - many of them bordering the sea or expanses of water such as mangroves in Kalba, others the desert. Nature and necessary journeys across it, is never far away. Take works displayed in Al Hamriyah Studios, in the far north of the Emirate, such as Alia Farid’s film installation Chibayish which chronicles the lives of children and water buffalo living in the Ahwar, southern marshlands of Iraq which has been devastatingly impacted by extractive industries and our ongoing ecological crisis. Ravon Chacon’s audio compositions infuse the eerie buried village of Al Madam, built in the 1980s, but the sandstorms prevalent there could not be tamed and it was only inhabited for a short time. Hugh Hayden’s Brier Patch has been installed there, and will remain - the tangle of tree branches sprouting from 100 school desks, will be ravaged by nature.

The most explicit site for investigating the integral topic of trade and exchange is another space built in the 1980s and subsequently abandoned: Old Al Jubail Vegetable Market in Sharjah City. The original shopfronts, interiors and curved arcade remain, and house projects which engage with histories of the breakdown of global economies as a result of conflict, such as the powerful series of interventions by Aziz Hazara. The artist collective Sakiya work from a historic farm near Ramallah, providing residencies and research programmes - their Water Witnesses totem sculptures are powerful statements of the need to return to pre-colonial histories to reclaim lost narratives. Anga Art Collective, based in a forest near Assam in northeastern India create work which acknowledges the shared histories and fragilities of agrarian communities.

SERAPIS MARITIME present MOTHER TRADE as a public art piece facing the sea beside Sharjah Art Foundation’s main spaces. Created in collaboration with local craftspeople and the Sharjah Maritime Academy, the work is a tribute to regional maritime history and trade.

Related Articles

Read more +07 October 2025 By Sibel Moyano in ITINERANT TRAILS

Read more +07 October 2025 By Sibel Moyano in ITINERANT TRAILSA Practice of Resistance: Elif Uras’s Earth in their Hands

The Magazine

Recent Posts

-

A Practice of Resistance: Elif Uras’s Earth in their Hands

Solo Exhibition at Galerist, Istanbul 16 Sept t... -

Textile & Clay: Ancient to Contemporary Testimonies

.... -

Embroidery and Existence: Majd Abdel Hamid on Art and Identity

... -

Material Witnesses Commissions: Afsoon

... -

Material Witnesses Commissions: Lydia Delikoura

...

WANT TO STAY UPDATED WITH ITERARTE LATEST ACTIVITES AND NEWS?

Sign up to our newsletter to be one of the first people to access our new art, learn all about our latest launches, and receive invites to our exclusive online and offline art events.