- Home

- First Principle

- Jung: Role of the Artist

Jung: Role of the Artist

Jung: Role of the Artist

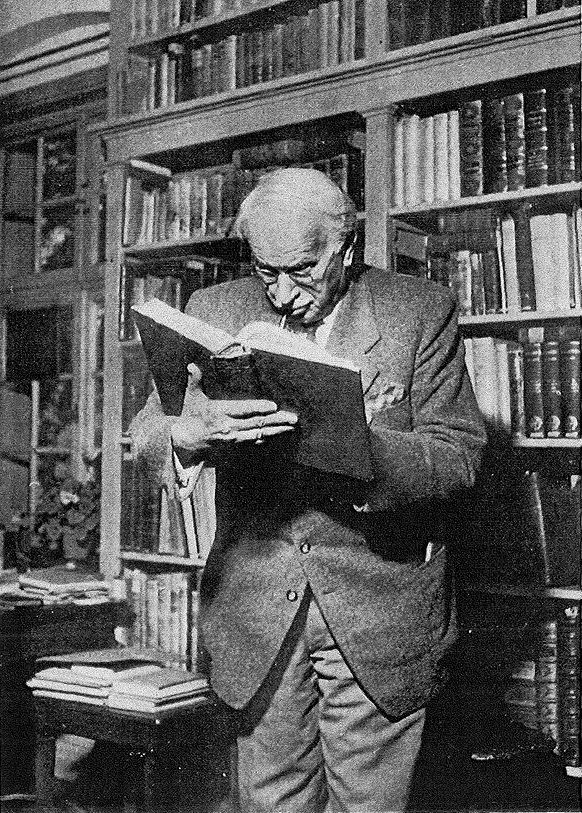

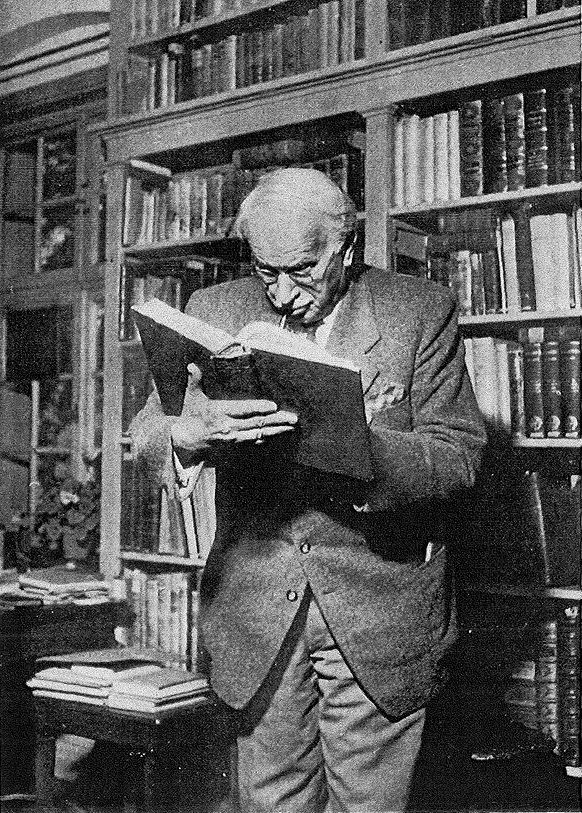

Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, who engaged in a longstanding friendship and feud with Sigmund Freud (the Austrian neurologist understood to be the founder of psychoanalysis), is known for his lasting contributions to the field of psychoanalysis. Jung proposed that artists play a vital, multi-faceted role in society, with their creative process offering catharsis on both personal and collective levels. Some of ITERARTE’s artists draw on his theories of the unconscious mind, and his emphasis on mythology and symbolism in conveying deeper truths about the human experience.

The Sinistry, in particular, are heavily influenced by the deeper layers of the psyche, consistently "looking at things that are invisible and bringing them down into a visible medium”, as shared with Laura Egerton in the recent ARTEculations podcast. Their work employs the unconscious and the use of symbolic language to shape a surrealist atmosphere, engaging with uncomfortable, unspoken themes - mirroring Jung’s approach. They seek to connect with the collective unconscious, which claims that some unconscious memories are inherited from past collective human experiences.

In the podcast, one-half of the duo, Bert Gilbert described the experience of being an artist as existential: she had no choice but to be an artist. Taking on a social responsibility, artists who engage with the collective unconscious allow others to resonate with the shared aspects of the human experience.

“As a human being, the artist may have many moods, and a will, and personal aims, but as an artist he is ‘man’ in a higher sense — he is ‘collective man’ — one who carries and shapes the unconscious, psychic life of mankind.” -Carl Jung, Spirit in Man, Art, And Literature (1966)

The titles of The Sinistry’s works provide an insight into their psychoanalytical process. For example, their (No) Shame Masks (2024), which refer to the literal and metaphorical acts of mask-wearing, are each labeled with humorous philosophical commentary, such as “Causeless Defects” and “Bored of Your Own Games?” These statements make reference to the deeper layers of the psyche, further explored by their use of recurring motifs such as eyes, snakes, and DNA molecules.

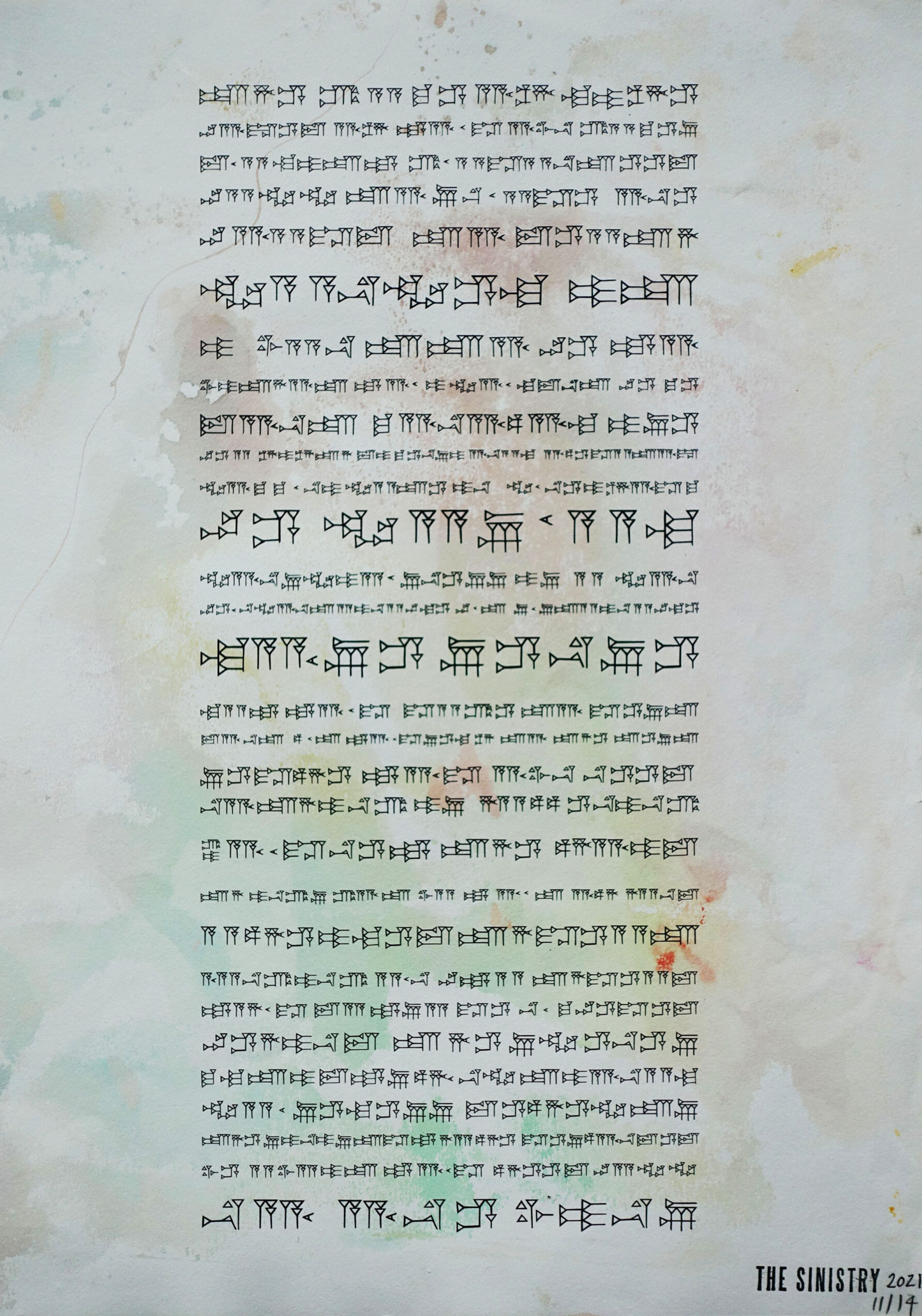

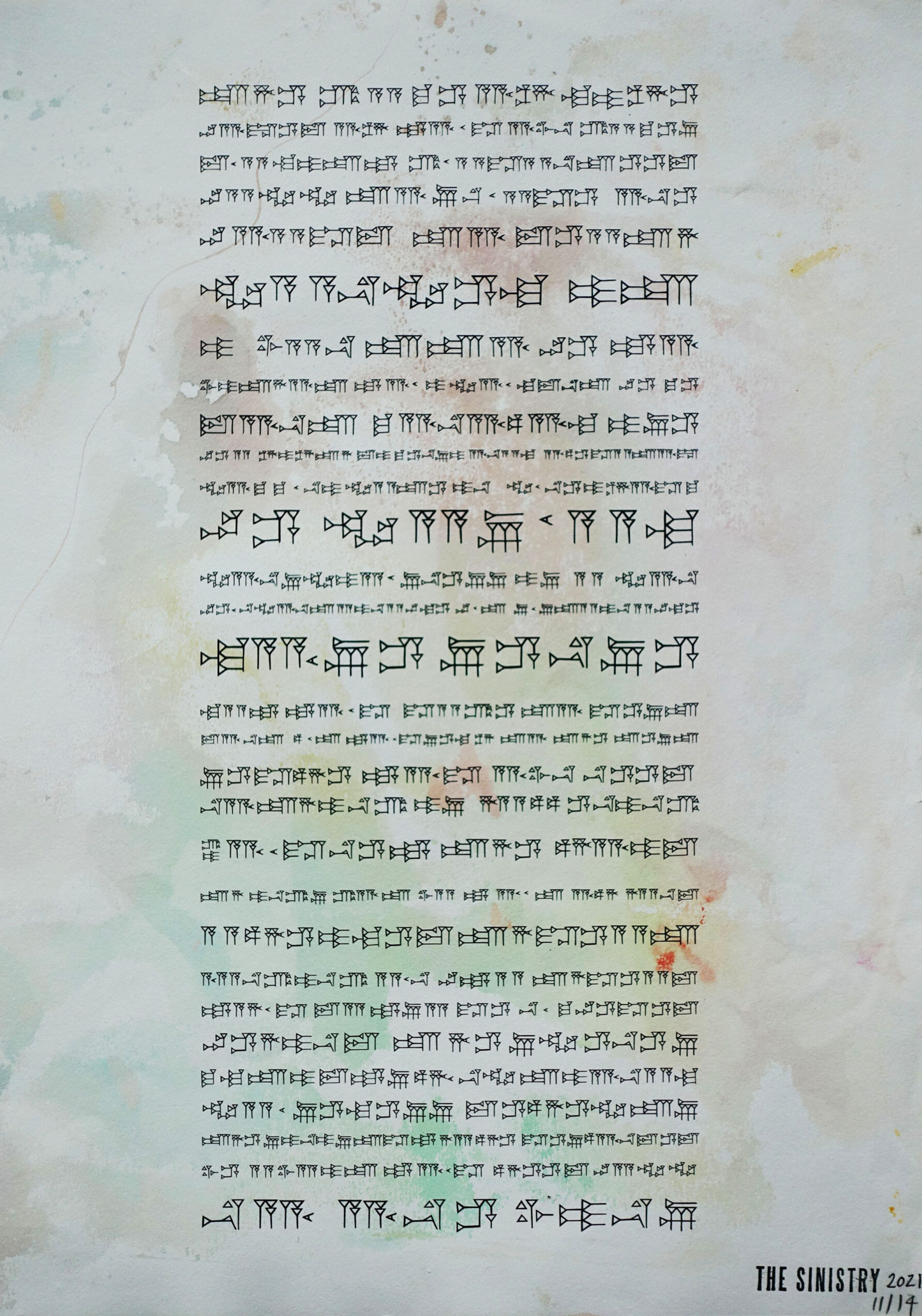

For The Sinistry, symbols are universal representations of complex ideas that transcend cultures and time, citing ancient cave markings as the earliest example of this concept. Their use of cuneiform, the oldest known alphabet, in their Game of Life manifesto highlights its ancient significance in the evolution of imagery and language.

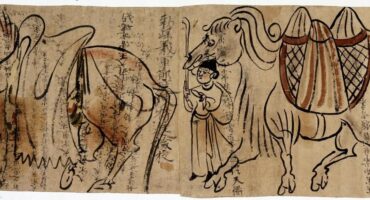

In contrast, Iraqi artist, Salam Atta Sabri applies ancient imagery in his visual interpretations of his homeland, Baghdad, connecting this history to place. Cultural iconography in his work ranges from Sumerian dolls to bricks, capturing his inner turmoil of displacement and the yearning for a lost homeland, which many Iraqis and non-Iraqis can resonate with. Atta Sabri's fun use of colour and illustration engages with fantasy, as well as a vision of his homeland's past through a child-like lens, presenting a psychological tension between the visible and the hidden.

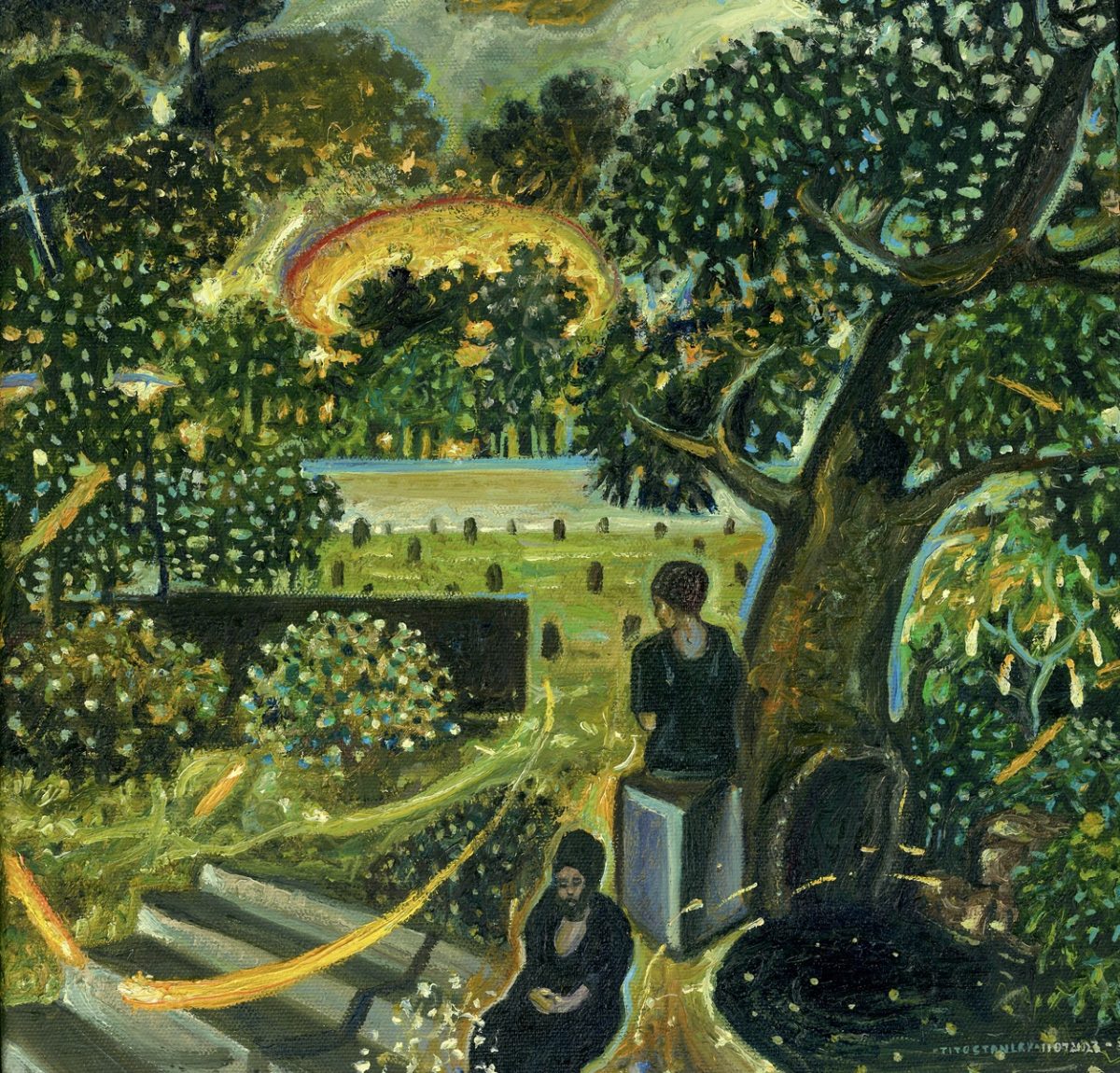

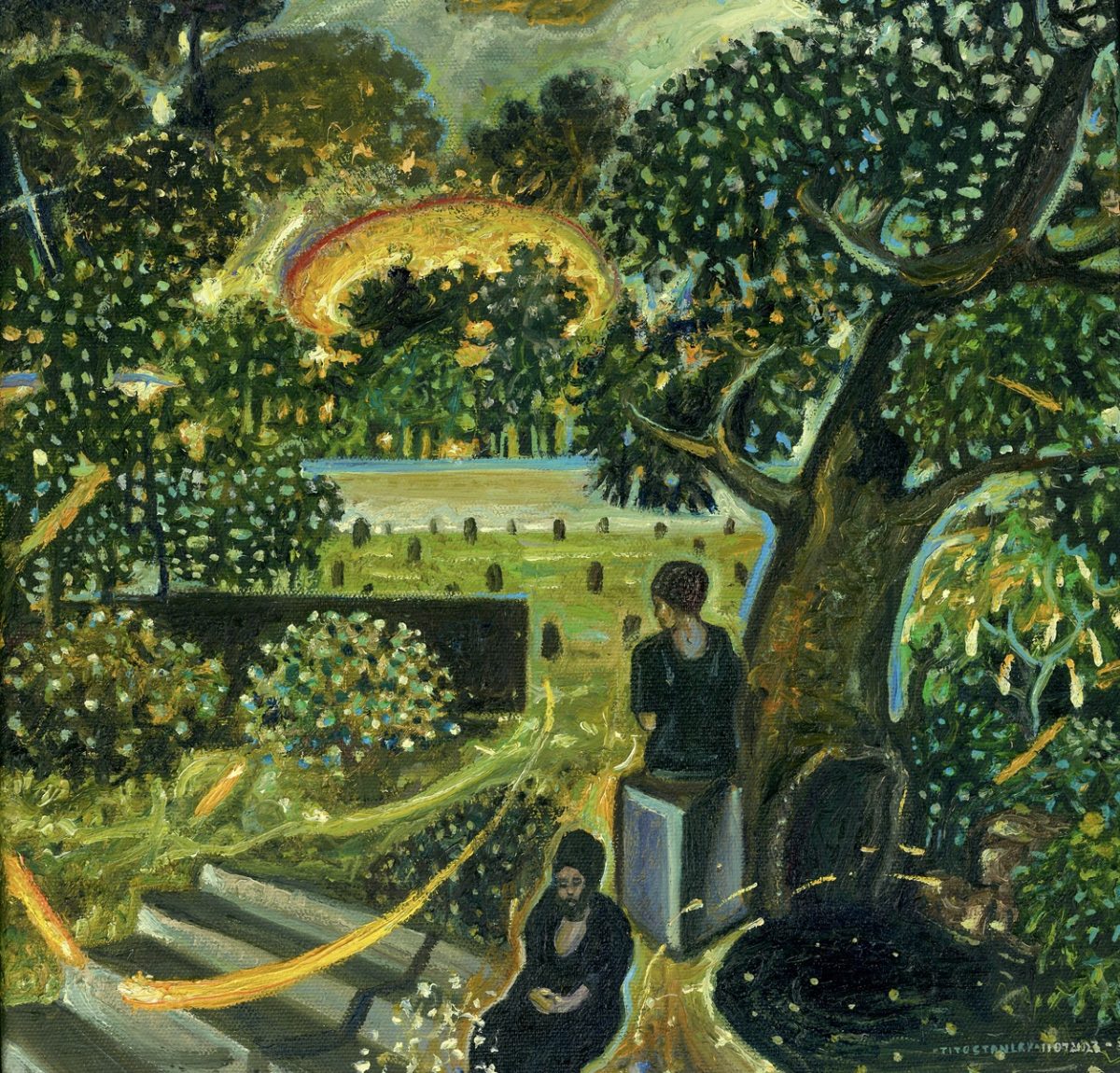

Mythology and religion play a significant role in Carl Jung’s collective unconscious concept, as these universal symbols, stories, and archetypes facilitate our access to shared human experiences. Tito Stanley’s mystical paintings delve deeply into the human psyche by exploring themes of life, death, and the broader cosmos. His work often reflects on how societies are shaped by religious rituals, spiritual beliefs, and the collective myths that bind communities together. In Fallen Stars, for example, Stanley intertwines celestial bodies with portraits of himself, blurring the line between the physical and metaphysical worlds. By using recurring archetypal symbols, Stanley engages with the unconscious, drawing from universal emotions and collective memories that transcend individual experience.

The Magazine

Recent Posts

-

A Practice of Resistance: Elif Uras’s Earth in their Hands

Solo Exhibition at Galerist, Istanbul 16 Sept t... -

Textile & Clay: Ancient to Contemporary Testimonies

.... -

Embroidery and Existence: Majd Abdel Hamid on Art and Identity

... -

Material Witnesses Commissions: Afsoon

... -

Material Witnesses Commissions: Lydia Delikoura

...

Jung also refers to the shadow, a repressed side of the psyche, as represented by ‘evil’ forces in mythology, embodying negative traits such as temptation and greed that we reject as parts of ourselves. Stories such as Odysseus feature confrontations with the shadow, and reflect our need to integrate the darker parts of the psyche to achieve greater self-awareness. Anselm Kiefer’s profound engagement with the shadow is evident in his art, where he intertwines historical events with mythology. By incorporating symbols, Kiefer confronts the darker aspects of human nature, often reflecting on the collective guilt tied to Germany's post-war identity. In Seraphim (1983-84), he uses the symbol of a snake- commonly associated with evil, in contrast to the title’s reference to angels. Kiefer also used fire to create its surface, alluding to the Latin term "holocaust”, meaning a sacrificial offering by fire.

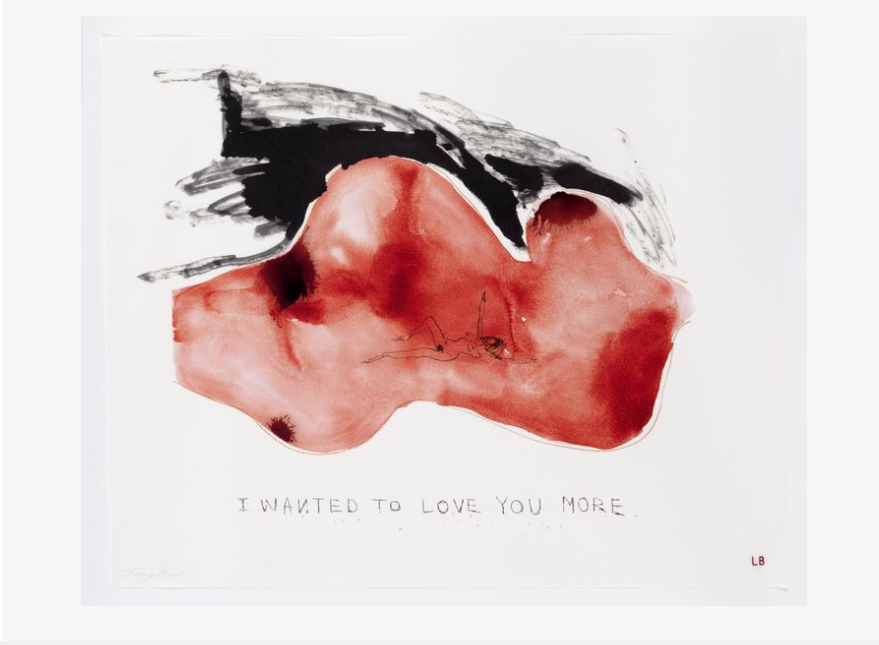

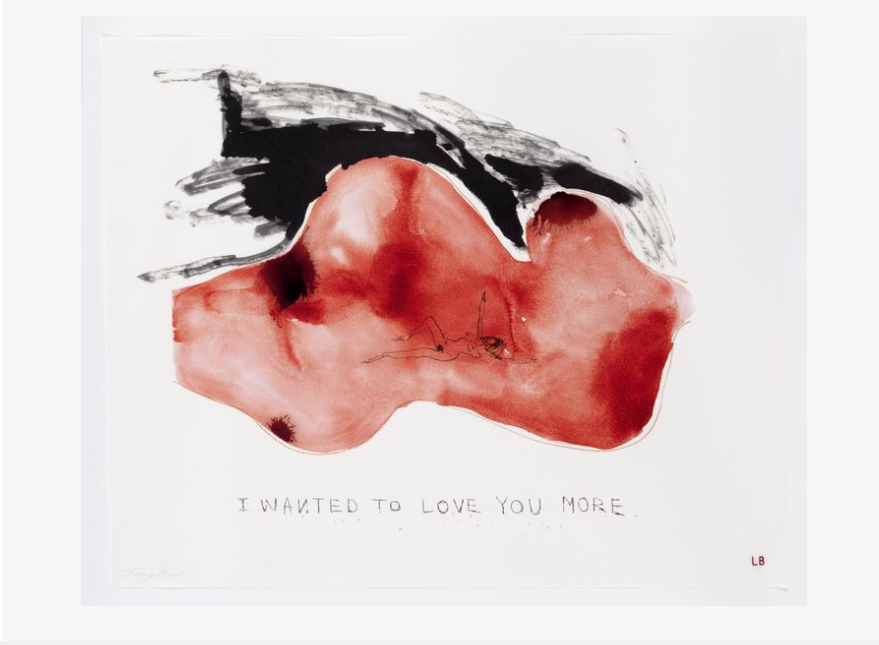

Trauma and healing can play a significant role in an artist’s journey, as practicing art can provide a powerful outlet for expressing innermost feelings. Jungian thinking emphasises the act of creating as a bridge between the conscious and unconscious, facilitating self-discovery and emotional integration. The late prolific artist, Louise Bourgeois would confront and reveal repressed aspects of her identity and childhood trauma in a visceral manner, allowing her a “guarantee of sanity”. Her cathartic process, seen in vast sculptures such as Spider (Cell) (1997), was later followed by her friend and collaborator, Tracey Emin. The pair worked together on a series of intimate paintings named Do Not Abandon Me shortly before Bourgeois’ death in 2010, unveiling honest accounts under themes such as identity, sexuality, and fear of loss and abandonment.

Artists have the unique ability to tap into universal motifs that resonate across cultures and time, serving as conduits between larger collective experiences and individual expression. By bringing to light stories and emotions we often repress in our daily lives, they foster deeper self-awareness and understanding within society as a whole.

Related Articles

Read more +19 February 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First Principle

Read more +19 February 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First PrincipleCultural Crossroads: Stories of Exchange

Read more +16 January 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First Principle

Read more +16 January 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First PrincipleEditions & Multiples: Art in Repetition

Read more +01 August 2024 By Melis Yilmaz in First Principle

Read more +01 August 2024 By Melis Yilmaz in First PrincipleThe Sea as a Subject Across Time and Cultures

Jung: Role of the Artist

Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, who engaged in a longstanding friendship and feud with Sigmund Freud (the Austrian neurologist understood to be the founder of psychoanalysis), is known for his lasting contributions to the field of psychoanalysis. Jung proposed that artists play a vital, multi-faceted role in society, with their creative process offering catharsis on both personal and collective levels. Some of ITERARTE’s artists draw on his theories of the unconscious mind, and his emphasis on mythology and symbolism in conveying deeper truths about the human experience.

The Sinistry, in particular, are heavily influenced by the deeper layers of the psyche, consistently "looking at things that are invisible and bringing them down into a visible medium”, as shared with Laura Egerton in the recent ARTEculations podcast. Their work employs the unconscious and the use of symbolic language to shape a surrealist atmosphere, engaging with uncomfortable, unspoken themes - mirroring Jung’s approach. They seek to connect with the collective unconscious, which claims that some unconscious memories are inherited from past collective human experiences.

In the podcast, one-half of the duo, Bert Gilbert described the experience of being an artist as existential: she had no choice but to be an artist. Taking on a social responsibility, artists who engage with the collective unconscious allow others to resonate with the shared aspects of the human experience.

“As a human being, the artist may have many moods, and a will, and personal aims, but as an artist he is ‘man’ in a higher sense — he is ‘collective man’ — one who carries and shapes the unconscious, psychic life of mankind.” -Carl Jung, Spirit in Man, Art, And Literature (1966)

The titles of The Sinistry’s works provide an insight into their psychoanalytical process. For example, their (No) Shame Masks (2024), which refer to the literal and metaphorical acts of mask-wearing, are each labeled with humorous philosophical commentary, such as “Causeless Defects” and “Bored of Your Own Games?” These statements make reference to the deeper layers of the psyche, further explored by their use of recurring motifs such as eyes, snakes, and DNA molecules.

For The Sinistry, symbols are universal representations of complex ideas that transcend cultures and time, citing ancient cave markings as the earliest example of this concept. Their use of cuneiform, the oldest known alphabet, in their Game of Life manifesto highlights its ancient significance in the evolution of imagery and language.

In contrast, Iraqi artist, Salam Atta Sabri applies ancient imagery in his visual interpretations of his homeland, Baghdad, connecting this history to place. Cultural iconography in his work ranges from Sumerian dolls to bricks, capturing his inner turmoil of displacement and the yearning for a lost homeland, which many Iraqis and non-Iraqis can resonate with. Atta Sabri's fun use of colour and illustration engages with fantasy, as well as a vision of his homeland's past through a child-like lens, presenting a psychological tension between the visible and the hidden.

Mythology and religion play a significant role in Carl Jung’s collective unconscious concept, as these universal symbols, stories, and archetypes facilitate our access to shared human experiences. Tito Stanley’s mystical paintings delve deeply into the human psyche by exploring themes of life, death, and the broader cosmos. His work often reflects on how societies are shaped by religious rituals, spiritual beliefs, and the collective myths that bind communities together. In Fallen Stars, for example, Stanley intertwines celestial bodies with portraits of himself, blurring the line between the physical and metaphysical worlds. By using recurring archetypal symbols, Stanley engages with the unconscious, drawing from universal emotions and collective memories that transcend individual experience.

The Magazine

Recent Posts

-

A Practice of Resistance: Elif Uras’s Earth in their Hands

Solo Exhibition at Galerist, Istanbul 16 Sept t... -

Textile & Clay: Ancient to Contemporary Testimonies

.... -

Embroidery and Existence: Majd Abdel Hamid on Art and Identity

... -

Material Witnesses Commissions: Afsoon

... -

Material Witnesses Commissions: Lydia Delikoura

...

Jung also refers to the shadow, a repressed side of the psyche, as represented by ‘evil’ forces in mythology, embodying negative traits such as temptation and greed that we reject as parts of ourselves. Stories such as Odysseus feature confrontations with the shadow, and reflect our need to integrate the darker parts of the psyche to achieve greater self-awareness. Anselm Kiefer’s profound engagement with the shadow is evident in his art, where he intertwines historical events with mythology. By incorporating symbols, Kiefer confronts the darker aspects of human nature, often reflecting on the collective guilt tied to Germany's post-war identity. In Seraphim (1983-84), he uses the symbol of a snake- commonly associated with evil, in contrast to the title’s reference to angels. Kiefer also used fire to create its surface, alluding to the Latin term "holocaust”, meaning a sacrificial offering by fire.

Trauma and healing can play a significant role in an artist’s journey, as practicing art can provide a powerful outlet for expressing innermost feelings. Jungian thinking emphasises the act of creating as a bridge between the conscious and unconscious, facilitating self-discovery and emotional integration. The late prolific artist, Louise Bourgeois would confront and reveal repressed aspects of her identity and childhood trauma in a visceral manner, allowing her a “guarantee of sanity”. Her cathartic process, seen in vast sculptures such as Spider (Cell) (1997), was later followed by her friend and collaborator, Tracey Emin. The pair worked together on a series of intimate paintings named Do Not Abandon Me shortly before Bourgeois’ death in 2010, unveiling honest accounts under themes such as identity, sexuality, and fear of loss and abandonment.

Artists have the unique ability to tap into universal motifs that resonate across cultures and time, serving as conduits between larger collective experiences and individual expression. By bringing to light stories and emotions we often repress in our daily lives, they foster deeper self-awareness and understanding within society as a whole.

Related Articles

Read more +19 February 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First Principle

Read more +19 February 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First PrincipleCultural Crossroads: Stories of Exchange

Read more +16 January 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First Principle

Read more +16 January 2025 By Melis Yilmaz in First PrincipleEditions & Multiples: Art in Repetition

Read more +01 August 2024 By Melis Yilmaz in First Principle

Read more +01 August 2024 By Melis Yilmaz in First PrincipleThe Sea as a Subject Across Time and Cultures

WANT TO STAY UPDATED WITH ITERARTE LATEST ACTIVITES AND NEWS?

Sign up to our newsletter to be one of the first people to access our new art, learn all about our latest launches, and receive invites to our exclusive online and offline art events.